For many filmgoers, Bryan Singer’s original X-Men – released in 2000 – served as one the first successful examples of a modern superhero/comic movie. Since then there have been three other pics based directly on Marvel’s mutant characters, plus two Wolverine spin-offs. Now Singer returns with X-Men: Days of Future Past, in which mutants in the near future, and in the past, fight a new war.

The film features a raft of visual effects challenges, from polymer-based 1970s ‘Sentinel’ robots to future shapeshifting versions of the same thing; mutants with speed, fire, ice, transformation and portal-ing powers; and destruction and battle scenes in 1970s Washington D.C. and the future.

Days of Future Past was captured by DOP Newton Thomas Sigel shooting with with ARRI Alexas on 3Ality stereo rigs in and around Montreal. A number of key action sequences were shot mono and then post-converted by Stereo D. Leading the effects charge was VFX supervisor Richard Stammers and VFX producer Blondel Aidoo, who oversaw the work of several facilities: MPC, Digital Domain, Rhythm & Hues, Rising Sun Pictures, Mokko Studio, Cinesite, FUEL VFX, Vision Globale, Hydraulx, Method Studios and an in-house team. Legacy Effects handled a number of make-up effects, with Framestore contributing concept designs for the 1970s Sentinels and The Third Floor delivering previs and postvis services.

fxguide spoke to Richard Stammers and the major VFX houses to explore just some of the major effects sequences from the film.

Escape plan: Quicksilver

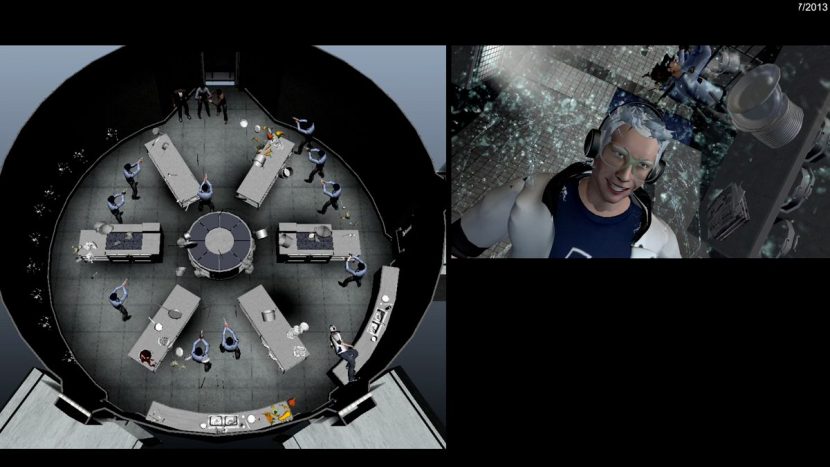

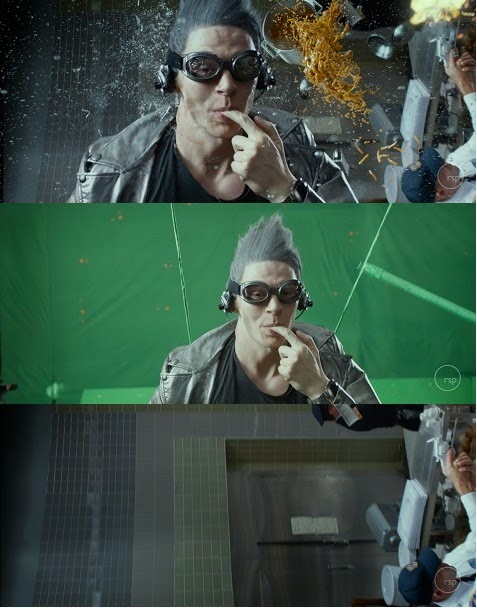

In what is perhaps one of the film’s most exhilarating sequences, the mutant Quicksilver (Evan Peters) uses his supersonic speed powers to help Charles Xavier (James McAvoy), Hank McCoy / Beast (Nicholas Hoult) and Wolverine (Hugh Jackman) break Magneto (Michael Fassbinder) from an underground bunker in the Pentagon. This is depicted in freeze-frame and slow-mo moments, with Quicksilver effectively moving at ‘normal’ speed amid water droplets from fire sprinklers, as well as flying food, bullets, cutlery and debris. Rising Sun Pictures crafted visual effects for the sequence under the supervision of Tim Crosbie.

The kitchen sequence, in particular, made heavy use of techvis from The Third Floor in order to work out how much of the shoot could be achieved in-camera. “Richard Stammers was concerned we’d have to do a digital double for a lot of the sequence,” says Bonang, “but I think we figured out how to do most of it with just the actor which was incredible.”

“Casey Schatz also went to the set,” adds Bonang, “and tested the camera himself to see if we could pull it off with a live-action actor. We got all the measurements from the sets and made sure there was enough space to do everything as intended. We’d start building the set in previs and then put a previs camera in there and we’d see that something was obstructing what we needed to see, so we were able to tell the set designer that the design might need to change slightly.”

The previs informed the filmmakers also as to the required photography set-up for slow motion. “We started with super slow motion 3D Phantom photography at 3200 frames per second,” explains Stammers, “so we could speed ramp to almost frozen and establish a live-action quality of the real sprinkler rain. We did substantial testing to hit the desired frame rate that ultimately was as fast as the Phantom could go while maintaining a 2K resolution. The stunt team also tested what would be effective to be seen at these speeds from self-punches to being hit by flying vegetables and air blasts. To maintain the light levels required for 3200 fps we used seven SoftSuns, which were integrated into the kitchen set build.”

In ‘Quicksilver time’, that is, when everything in the air is virtually static, these elements were created in CG and so required only normal shooting speeds. That meant that practical stunts could be filmed with a rotating wire rig to position Quicksilver on the wall with a track behind him. “For the front on shots,” adds Stammers, “where we see Quicksilver on the wall, we shot him as a green screen element running on a treadmill. We used the stereo Phantom rig to get close-up shots shooting at 250 frames per second to get a nice movement of wind blowing in his hair and rippling his face. Despite blasting his face with wind and rain none of this water showed up on camera so all the rain hitting his face is added as CG which required very detailed facial roto animation and complex fluid sims.”

Wider full body shots of Quicksilver on the wall were filmed with Peters running on a treadmill, captured with a Techno Dolly to create his movement in the frame. “We needed to see him dismount from the wall and change his body orientation 90 degrees during the action,” says Stammers, “so we cheated this with camera roll and lighting changes, whilst timing it perfectly with Evan Peters jumping from one treadmill to another that was slightly lower to the side. This gave us great gross body motion, which worked really well for the shot, but RSP had to replace Quicksilver’s legs digitally to get the detailed foot placement that was required.”

As Quicksilver races around the kitchen, his speed causes drag on objects in the air as they are pulled into his wake. “Many of the shots already required complex stunt work,” notes Stammers, “so adding rain, flying vegetables and soup into the mix is going to be too much, besides we could never shoot at a high enough frame rate for all the objects to appear static enough.”

“We did, however,” says Stammers, “get the art department to build some frozen fluid sculptures of saucepans with soup coming out of them to be practically dressed into some of the frozen moment shots. So for the most part we knew most shots would require the kitchen being filled with a volume of rain, pots, pans, cutlery, fruit and vegetables all hanging in the air during the scene. It was much more efficient way of repeating the setup and maintaining continuity throughout the whole sequence.”

The guards, rendered static by Quicksilver’s speed, are puppeteered into various positions by the mutant so that they were eventually punch themselves or topple when things return to normal speed. “Each of the puppeteering shots involved the guards standing perfectly still and allowing Quicksilver to move at ‘normal human speed’ and move them into new positions,” says Stammers. “These were photographed at 120 fps to give us extra frames as we needed to speed ramp theses shots. I did camera tests to try out this effect with Matt Sloan, my second unit VFX supervisor, to make sure this methodology would work on the day. In post we had to do a little bit of body stabilising to make sure everyone was really still and were not wobbling from Quicksilver’s movement interaction. From this we created a detailed body roto animation of all the actors and the objects in the scene so that we can place CG rain, cutlery and vegetables around them.”

Rising Sun Pictures began its CG and simulation work with a 3D LIDAR scan of the kitchen set. “Artists used it to create a detailed 3D model of the set to serve as a guide in the placement and choreography of CG assets, as a tracking tool, and for plotting lighting,” outlines Crosbie. “There was a big emphasis at the outset on the design of the room — we needed to control and manage that world. We acquired principal photography reference of the set in depth, every counter, every prop, every situation, and from there we came up with a list of what we needed to build. The animation team ultimately built nearly 100 unique items for the sequence (many of which were employed multiple times), many developed from cyber scans and texture data derived from practical props and set pieces.”

The look of the fluids and bullets was an aspect Rising Sun considered by first referencing slow-mo footage. “Many of us have seen slow-mo fluids on YouTube in one form or another,” states Crosbie, “but in this case we’re slowing down some of the shots to rates that are currently not seen with even the fastest production cameras available. As an example we were able to source a lot of still footage of bullets leaving gun barrels, but for moving footage even at 3000 fps the bullet’s gone too quickly. so we had to extrapolate and produce something that looked believable as well as cool.”

Other elements – which ranged from cooking utensils to cutlery and vegetables – were modeled and rendered in high detail. HDRs aided in lighting the kitchen and objects, with light coming from overhead range hoods, a fire and bounce light from the tiles.

Raindrops, in particular, were challenging since they would get hit or moved out of Quicksilver’s path and wake – effectively making a ‘rain tunnel’. “We had to set up a workflow that was able to be creatively adjusted depending on the shot,” says Crosbie. “We see Quicksilver from many angles and one setup or simulation paradigm was unlikely to work for all of them. For example, when we’re in front of Quicksilver, some of the characteristics of his trail needed to be amped up to get a good read, but when we’re behind him, following in his wake, if we kept the same levels and simulation settings he was mostly obscured because the characteristics felt different to the eye.”

In the future to save the past

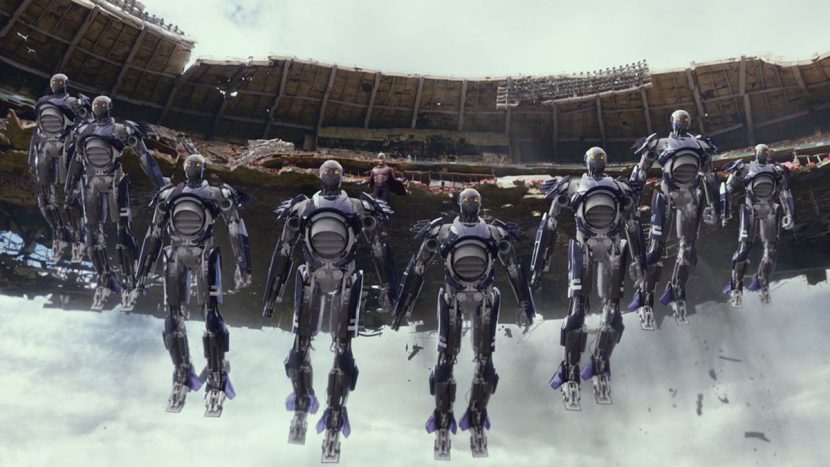

The film opens in a dystopian future where the Sentinel program has resulted in the extermination of most mutants, but also the oppression of humans. A handful of mutants battle the Sentinels in a Moscow sequence that exhibits the power of Shadowcat (Ellen Page) to project a person’s consciousness back in time – a power that will later be used to send Wolverine back to 1973 at a crucial moment in the Sentinel program.

Above: see breakdowns of the future Sentinels in this video made with our media partners WIRED.

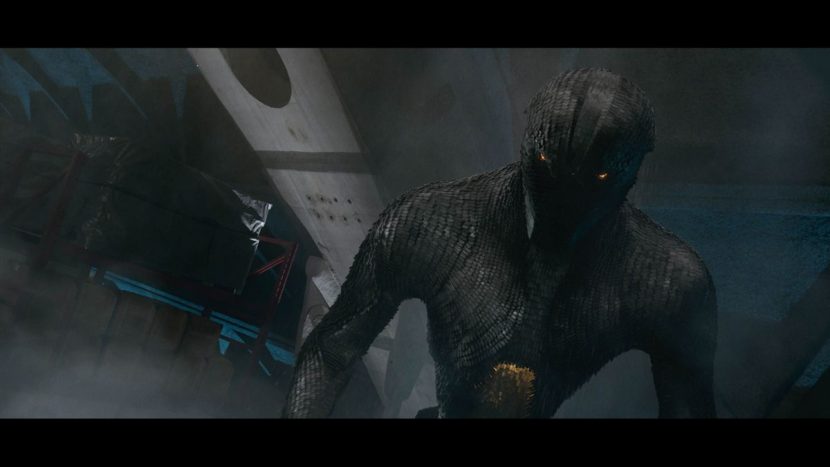

The look of the future Sentinels was based on the ability of 1970s military scientist Bolivar Trask (Peter Dinklage) to harness the power of Mystique’s DNA. Framestore and MPC led the concept process. MPC then created the final Sentinels, with much of the studio’s effects work also handled for the first time out of its Montreal office. “The Sentinels have surface scales in the same way that Mystique’s character does, but it’s more of a mechanical thing,” notes Stammers. “They also have the ability to transform and change their own abilities to work against whichever mutant they’re fighting. In Bryan’s mind there’s a lot more internal complexity to these things as robots so they use nanotechnology and the ability to really change things almost at a molecular level.”

MPC visual effects supervisor Anders Langlands oversaw the original idea of the Sentinel system of scales, blades and ‘flaring’ that mimicked Mystique’s abilities. Ultimately, the Sentinels would incorporate 100,835 blades and 1019 moving parts inside the face – which opened up as an extra weapon against adversaries.

The studio’s initial R&D involved taking their existing hair and fur tool, Furtility, which allowed for procedural animation and caching, and adapting it for the scales. However, after further development, MPC ended up introducing the idea of a proxy representation of each individual scale or what became known as a ‘follicle’. “The proxy representation was meant to allow us to have a lightweight representation of the final render model,” explains MPC CG supervisor Sheldon Stopsack, “and then we’d be able to swap these out at render time to have a more complex hi-res representation of each individual scale. Or we could have swapped that into something different that could have been a shader variation or a model variation.”

Watch the opening battle.MPC rigging lead Sam Berry oversaw rigging of the creature and worked on tools in modeling that helped lay out rows of proxy blades along nurbs patches built on top of the base Sentinel. “This ended up being a quite sophisticated tool that allowed us to design the distribution, orientation, flaring and random orientation of each proxy blade,” says Stopsack. “An interesting fact is that we also integrated rig function for collision avoidance of each blade. The blades had to be quite versatile for flaring and other transformation, so it was important to have a mechanism in place that avoided that problem, without spending too much time in clean up once cached.”

Animation supervisor Benoit Dubuc and his team developed key poses which helped sell the threatening nature of the Sentinels, despite the beings not possessing the usual facial features. “They did such a great job of striking those poses in a way that gave the right intention for the look,” comments Stammers. “It’s amazing without those usual ranges of expression how much you can do just with body language and the angle of the head relative to camera, chin down, looking through eyebrows.”

Scale animation – which rippled across the Sentinel’s body – was cached out as a point cloud and stored as matrices with various parameters – position, orientation or blade ID. MPC software lead Tony Micilotta was involved in having the point data cached, transferred and represented in Katana. “He handled the whole logic of instancing a high res representation of the blade,” says Stopsack. “We also had to integrate a logic that allowed us to prune, swap and dynamically change blades based on primvar passed through via the point data.”

“It’s worth mentioning that the whole system had to work with two type of approaches,” adds Stopsack. “One where single blades were swapped from proxy to high res geo per point. And one where we had to manually build a group of blades (for the head for example). The reason is the layout of individual blades along nurbs patches didn’t give us enough detail in the final sculpt / model. So the solution was to support custom models (group of blades) that could be handled with the same PTC approach.”

Lighting the Sentinels was overseen by lighting lead Chris Elmer, who drove look development from a shading point of view. Stopsack notes that the use of a bespoke Katana Scene Graph Generator meant that artists could isolate individual blades and aspects of the Sentinel model where necessary. “For the lighters,” says Stopsack, “it was rather convenient because you still had the flexibility to color individual blades or swap them out for other models if you needed to.”

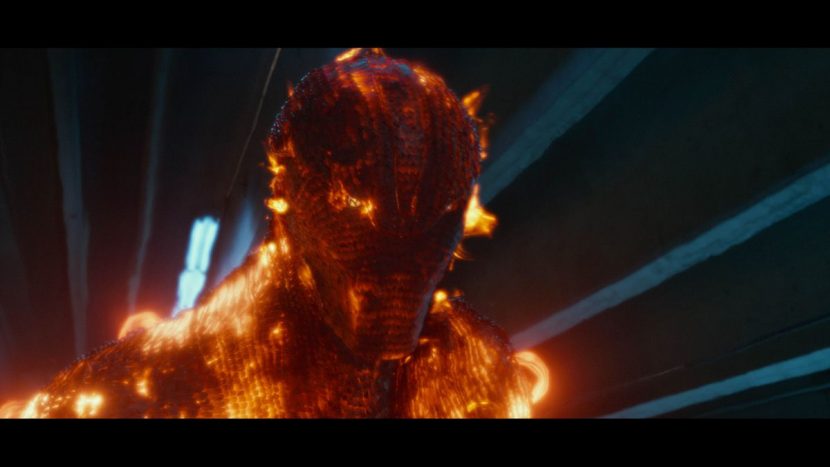

As the Sentinels take on a number of mutants, they are able to absorb and share powers, including those representing fire, ice and metal skinning. “We had built the Sentinels as a classic character on the inside,” describes Stopsack. “They had a proper under-body structure and a traditionally modeled geometric shape and pipes underneath, which means we could see the powers coming from the inner structure of the Sentinels. We had a heated core, say, that we did with a body shading approach that was temperature-driven. Then this temperature went to the top surface where the scales were.”

Helping to orchestrate that opening battle was previs outfit The Third Floor, led by previsualization supervisor Austin Bonang. Since the Sentinel and mutant action involved many key actions and powers, the film work was greatly assisted by a virtual camera volume set up by The Third Floor in Montreal. “By putting people in mocap suits, we could block out the Sentinels behavior in real time, how they attacked the mutants and how each mutant responded in return,” explains Bonang. “Each mutant had a particular way of interacting when they fought a Sentinel so there were different individual scenarios for this.”

The virtual camera volume designed by The Third Floor’s Casey Schatz incorporated simulcam with The Third Floor’s usual Xsens MVN capture suit set-up. “It is like a game controller with a viewfinder that hooks into the computer and the volume,” says Bonang. “It acts like a camera but it has a joystick so you can zoom and dolly and track and pan. The volume also tracks the operator’s movement within the virtual space. We’d have artists animate actions and then load those into the volume so the director or VFX supervisor or myself could come in and frame that action from different angles and we could get various camera angles very quickly with outputs to Motion Builder.”

Stammers and second unit director Brian Smrz were key contributors to the ‘virtual shoot’. “This meant,” says Stammers, “when it came to shooting things for real, they could only answer to themselves. That for me was a real win-win situation. We got really good action shots that they both liked and we also got the editor John Ottman involved in cutting the previs together. So from that point of view, all the filmmakers were involved in it rather than being alienated from it, which can often happen in other productions.”

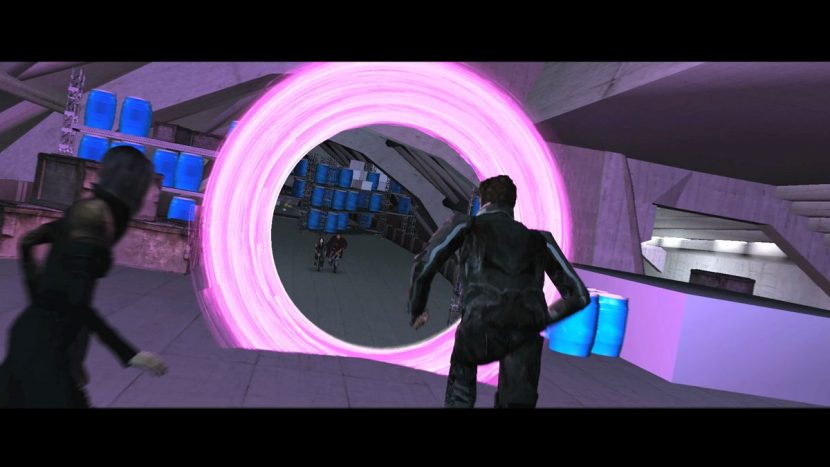

One of the first powers demonstrated in the battle is that of Blink (Fan Bingbing), who is able to create portals through which to teleport. MPC mixed a combination of technical animation, effects sims and 3D effects crafted in NUKE to produce the portals. “You end up with some incredibly complex moments where Blink is using portals to allow her mutant companions to get an advantage over the Sentinels to get them into better position to fight them,” says Stammers. “Every time a portal would open it’s like a window to where she’s come from. There’s an entry portal and exit portal and you’re basically seeing a window through to this view to where someone has come from.”

“It made shooting challenging,” adds Stammers, “because it’s like, OK, we’ve got a shot with a portal in it but we also need the plates of the view through the portal and all the people that are in there and the action that’s happening in there. So sometimes we were having to see animation and action from different angles in the same shot because the portal was giving us a different view to it. We worked out pretty much everything in advance with some pretty extensive previs – just to make sure we didn’t mess it up.”

Sunspot (Adan Canto) uses his powers on a Sentinel, harnessing the sun’s energy to fire projectiles like solar flares. MPC referenced NASA footage of the sun and then scaled that down to work on a human-sized character. “For the flares he was shooting,” explains Stopsack, “we used Flowline as our fluid simulation. We also combined that with different techniques to affect different Flowline caches and tried to use particle simulations to create volume. For the flares on the surface of Sunspot himself we used a mixed approach where we made up dynamic curves and arches around the surface which was more like a point simulation. We used a shader approach for Sunspot himself – it was marshmallow geometry around Sunspot and we used a ray marching approach to create close proximity flares and flaring effects on the surface.”

Iceman (Shawn Ashmore) also attempts to use his mutant powers on the Sentinels – his entire face and body ices over and he also creates ice flights as swift transport. “We started with a milky ice approach with that sub-surface approach, to foggy and to be completely clear,” says Stopsack. “We tried to find the right balance and ended up with a mix of having enough detail to capture within the ice the structure and drive the exposed and roughness of the surface. It was almost like a normals texture approach – if you texture for the specular components of the human face, the way you want to drive different parts of the face based on the oilyness – the reflectance basically. We started doing something similar for Bobby – driving the exponent and roughness of the eyes in a certain expression.”

Practical photography based on previs involved significant wire work to mimic the undulating ice flight surfaces. MPC then blocked out and rigged the ice flights as geometric models. “We had the ability to collapse these and be able to reveal them as they were required as Iceman was traveling on them,” comments Stopsack. “We used the curvature or any primitive we could pass on to add variety rather than it being a uniform surface which can look cool but doesn’t hold the complexity we were after. Then we had icicles, pinnacles and set dressing. Plus an ice formation used to enclose and capture the Sentinels, which was a more effects-driven thing. We used classical point simulations to create these fields of geometry and used with the same shader methodology – how glossy or non-glossy it was meant to be.”

MPC also delivered effects shots for other mutants in the opening fight, including Bishop (Omar Sy), who is able to absorb powers and redirect them as kinetic blasts, and Colossus (Daniel Cudmore), who grows a super-strong steel skin. The studio, as it had done for other characters, made extensive use of roto-mation to preserve the actor performances. “For Colossus, in particular,” notes Stopsack, “we explored the idea of using vector maps for certain parts of the displacement. We knew if we dealt with certain scenes where the displacement grew from the arms it got quite close to camera – it was just a little bit more independent in terms of screen size. So we used vector maps for displacement to be ready for any kind of screen space or screen size.”

A second major battle against the future Sentinels is intercut later in the film with a 1973 mutant / Sentinel clash in Washington D.C. MPC worked on the future sequence involving Storm (Halle Berry), Magneto (Ian McKellen), among other mutants who are holed up at a Chinese monastery. The studio produced an extensive environment build for the mountains and monastery, plus animation and destruction effects as the X-Jet becomes a weapon against the Sentinels.

The Beast in all of us

Back in 1973, Hank McCoy / Beast is now living with Charles Xavier in the X-Mansion, and is struggling with his mutant powers as Wolverine arrives from the future to notify them of the impending doom. McCoy’s transformations into Beast at crucial moments in the film were handled by Rhythm & Hues, led by visual effects supervisor Derek Spears.

Legacy Effects delivered Beast make-up effects. “It was designed by Scott Patton and sculpted by Scott Stoddard, who also was the key make-up artist from Legacy Effects along with Brian Sipe and Michael Ornelaz,” says Legacy co-founder John Rosengrant. “It was very important to allow Nick Holt to not be buried in make-up so thick that he couldn’t articulate facial expressions and keep it looking as natural as you can make a Blue feral guy!”

Wolverine meets Beast.For Hank to Beast, Rhythm & Hues began with a live action Nicholas Hoult plate, using a slight head dip in the actor’s performance to transition into a CG Hoult before transforming into a CG beast and through to Hoult again in Beast make-up. “That’s handled by morph targets going from the CG side of Hank to the CG side of Beast,” explains Spears, “and then our tech anim team grew the hair out. We had a version of Hank’s hair and Beast’s hair and a section of Hank’s hair would grow out from underneath that and transform through it.”

The CG builds of Hank and Beast involved scans and photography of the actor with and without makeup. Models were crafted in Maya and then animation, rigging and tech anim completed in Rhythm’s proprietary Voodoo toolset, with rendering carried out in the studio’s Wren software, and compositing done in NUKE.

Artists adopted a roto-capture approach to begin the transformation process. “We’d start with detailed tracks to capture the performance,” says Spears, “and then the animator could go in and embellish that with the correct shapes and fine detail such as mouth and eye positions, say the way the eye drags when the eyeball moves.”

The hair transformations proved to be some of the most challenging work. “The hair targets had to be a little bit shot specific because he wasn’t groomed exactly the same way in every shot,” says Spears. The cloth animation, too, required high resolution cloth sims in order to deal with loose fitting clothing on Hank becoming tighter on Beast. “We threw a lot of vertices at it,” notes Spears. “We just up’d the mesh res’s and the cloth sims would run from anywhere from 8 to 24 hours just for one piece of clothing.”

Above: explore Beast further in this ‘Power Piece’.

Part of the transformation from Hank to Beast, for example, involved a color change, done via skin shaders but also augmented in comp through the appearance of veins in the character’s face. Says Spears: “We procedurally generated vein mattes, and handed those to the compositor as a way to transition from one side to the another to make it not look like a dissolve-y morph. So the way that color grows on is very organic.”

“The opposite is true going from Beast back to Hank,” adds Spears. “The veins going in reverse looked a bit silly so we ended up with a procedural shader which erased the skin, so all those mattes were used by the compositor to make the transition work back. And in Beast to Hank we are fully CG on both sides. Although we did use the underlying performances to drive those, we didn’t use any actual pixels.”

Modern Mystique

Mystique’s transformation abilities have been on show, of course, in prior X-Men films. This time around, Singer had sought even more detail and for them to appear slower in the manner in which the character’s ‘scales’ flip over to reveal another character underneath. Digital Domain handled the Mystique shape-shifts, led by visual effects supervisor Lou Pecora. “We took the perspective of,” says Pecora, “if there was really something like this out in the world, how would it happen? How would it really do what it does? We came up with the idea of the card flip where you flip one and the whole thing rolls over. There’s a physical reality in those where those cards are pivoting over.”

On set, Jennifer Lawrence, who plays Mystique, wore make-up effects appliances made by Legacy Effects. It was important to make Mystique beautiful, sexy and dangerous,” says Legacy’s John Rosengrant. “The main designer here at Legacy Scott Patton and Darnell Isom really planned out the pattern of the scales and reduced them in size and placed them to accentuate Jennifer’s face and have a nice flow on the body. We broke new ground in that her prosthetic appliances were almost digitally sculpted and rapid prototyped, allowing for precise control and proper look. Allowing Jennifer to come through the make-up was important to us.”

Mystique makes an appearance at a Vietnamese army camp.An overriding desire from the filmmakers was that the transformations never appeared to be a wipe. “There was a ‘no wipe mantra’ from the beginning,” states Pecora. “If you stepped through it frame by frame, you don’t see an awkward moment of dissolve. In the end, there were a few, particular in the finer features on the face – there are some points where you just have to do this because if they’re too small she looks like she’s got a stubbly beard.”

Although the principle behind Mystique’s tiles or feathers was that they flipped to reveal another person – as if on hinges – Digital Domain had to keep that concept flexible depending on the nature of the shot. “We found on the close-ups the feathers were a certain size and then when you go wide they looked too small so they had to look bigger,” says Pecora. “The silhouette was very important when you watched the shape of the thing transforming. In order to maintain cohesion from close to far we were able to scale those feathers accordingly to make it work.”

Live action photography for the character shifts involved deceptively simple set-ups, according to Pecora. “You shoot one actor, then you shoot the other, and hopefully you get them in roughly the same place,” he notes. “But of course they’re never perfectly lined up. Jennifer Lawrence is of course very feminine and some of the guys she changes into are certainly not, particularly the Nixon shapeshift.”

DD would line up the characters as well as possible and then rely on a 3D blendshape to move between the two. “You use that as a skeleton to put your feathers on,” explains Pecora. “So then all the feathers grow out of that blendshape. You go back and refine all the tracking in there and roto-capture the body and try to find a place where they line up as much as possible.”

Mystique transforms into a Vietnamese General.One particular transformation takes place in Paris where Mystique is disguised as a Vietnamese General. Here, production filmed multiple passes of the actors with motion control. “The moco is really good,” notes Pecora. “The table and the window, I mean, they were the same in every take. But the people and the hero and stunt double and the Jennifer were different every time. So we were using an arm from this take and a leg from that take and then coming up with the geometry to match. So you’d end up with a 2D timing and overall blend wipe to get the timing bought off on in editorial. Then you back in your 3D blendshapes and tracking into that and then that’s the framework your feathers go onto.”

The feathers themselves were full CG geometry builds from Digital Domain, with some projections for textures where necessary, such as where Mystique as an army Colonel walks from a plane and then transforms. “The walk was different, the cycle was different, everything was different but we use projections from various points within the footage to project onto geometry to get the geometry in there,” outlines Pecora. “And if those stretched or failed you’d have to paint stuff to fill it in.”

Digital Domain and Mokko Studio also crafted many shots of Mystique’s distinctive yellow eyes in CG, since on set, Jennifer Lawrence did not wear any make-up effects contact lenses.

Washington D.C., in 1973

Now intent on creating his own version of the future, Magneto arrives at Washington D.C.’s RFK Stadium and proceeds to tear it from the ground before transporting the structure to surround the White House where Trask is unveiling his new Sentinels. Digital Domain delivered shots of the partial stadium destruction and uprooting.

The Washington D.C stadium lift-off scene and the ensuing battle at the White House were also previs’d by The Third Floor. They modeled the stadium and relied on a basic layout of Washington to choreograph how the structure would be moved by Magneto to its new resting place. For shots involving debris and destruction, The Third Floor relied on pre-animated geometry and ‘Zoetrope’ cards. “These are basically pre-recorded movies with effects like smoke or fire,” explains Third Floor’s Austin Bonang, “that are placed on a transparency card or a plane in 3D space. They provide 2D effects in a 3D space to simulate say a large plume of smoke being kicked up by a falling rock.”

Principal photography was shot on a small baseball field in Montreal without any seating. “We pretty much had greenscreen around him wherever we could,” says Stammers. “DD’s team then went to the stadium in D.C. and did a fairly extensive texture shoot and LIDAR scan, and built a fantastic version of the stadium.”

That version was based on reference material and detective work Digital Domain had carried out to match the 1970s look and feel of the stadium, including period advertising banners. Then the structure was created in ‘pie wedges’, as DD’s Lou Pecora explains: “We looked at it in terms of a clock – we said, ‘OK we’ll cover in from ten to noon and that was the coverage area we needed. This way we didn’t have to over-render it or under-use it.”

As Magneto harnesses the re-bar and metal in the stadium to lift it into the air, artists orchestrated breaks and cracking, along with RBD sims done in Houdini and rendered via V-Ray through Maya. He transports the stadium to the White House, an area mostly synthetically generated by Digital Domain based on some aerial footage and photographs in consultation with a Washington historian.

The stadium drops and the surrounding dust and debris cloud envelops approaching police and passers-by – effectively keeping them out of the area. Digital Domain paid particular attention to the consistency of the dust in those scenes. “One thing I notice in a lot of movies is that all the dust is the same color,” says Pecora. “It has the same hue and luminance and to me that always blows the scale. So I was a broken record about it – I wanted some dust to be brown, some of it dirt, some of it grey, some a ruddier color. And I wanted to have it even behave a little differently, sometimes it’s heavier or lighter. This way it feels big. I drove my effects guy crazy about it!

Scenes in front of the White House – where Trask unveils his Sentinels – were filmed in Montreal. “We built an exterior set and surrounded it with a 360 degree greenscreen and a silk roof for consistent lighting,” says Stammers. “Digital Domain extended everything around it with a full CG build of the White House lawn, the wings, trees, fountain.”

The 1973 version of the Sentinels were, like their future versions, a major design challenge for the filmmakers. Ultimately they were realized as 18 foot tall robots made out of a space-age polymer. “We looked back to product designs from the 70s,” says Stammers, “things that looked very futuristic in the 70s, like concept cars and classy sports cars, and used a lot of that as a design reference.”

Framestore was engaged to design the 1973 Sentinels, with a full-scale practical model then built for reference and use in the film by Legacy Effects. “We took the 3D models from production and tightened them up for our purposes of creating the full size 18′ version,” explains Legacy’s John Rosengrant. “Simultaneously, our Model shop and Mechanical department worked with the CG artists here at Legacy and built in allowances for the inner support structure and joints. The full size construction was a combination of rapid prototyped pieces that were either molded or turned into vaccu-form pieces. The outer shells were all large vaccu-form clear pieces. The other main challenge was how to hang translucent shells onto the support structure with nothing appearing to be made of metal but all made in some type of plastic.”

To obtain the right plastic look, Legacy used mostly plastic material or treated fiberglass and epoxy. “Anything that was actually metal (support) was painted to look plastic in its finish,” adds Rosengrant. “The big body, leg etc. shells started out clear and were shot with thin translucent ‘candy’ car paint to achieve the correct color and feel. The design was created by the production designer John Mayhre.”

Matching the Framestore designs and Legacy build, Digital Domain created a robot model that included various levels of translucency and plastic-ness, doing a full lookdev in V-Ray via Maya. In designing the Sentinels’ motion, the filmmakers considered reference of current robotic articulation and fluidity. “We looked at ways the individual limbs would move and whether there was any kind of hard stops to the limb movement,” says Stammers. “We found that if it was too mechanical and clunky it just didn’t give us the right feel we wanted. We toned it down if it felt over-futuristic, say if they were over-compensating all the time and making micro-adjustments to stay in the same position. The couldn’t be too agile.”

With the world watching on television, Trask reveals the Sentinels but Magneto makes them operational (having earlier laced them with metallic wiring stripped from railroad tracks). Trask quickly escapes, along with President Nixon, to a White House bunker, but is extracted by Magneto. The sequence involved further CG destruction sim work by Digital Domain.

As this action plays out, various X-Men engage the Sentinels, including Beast who takes one head-on. On set, green poles with tennis balls and a green Sentinel head were utilized for the performance. “I’ll be honest with you,” relates Pecora, “when I saw those plates I thought, ‘Oh my God, how are we ever going to make this work?’ There was some paint reconstruction required, but I was surprised how well that ended up working. We put our CG Sentinel right on top of it and it lined up and seemed to work and we roto-captured that. The gravity and weight was right and we all looked at through a covered face. We had to only put him on a card and re-project him for one shot.”

Since the main photography for the Sentinel battles was filmed within the greenscreen and scrim exterior set, artists at DD relied less on the use of on-set HDRs for lighting and more on an artistic approach. “In an environment like the White House lawn,” relates Pecora, “if you really had a robot there you would have a bounce card there, but there was none. So HDRs took us only part of the way. The rest of the way was just calls we made artistically of where we wanted the light to be.”

Digital Domain also relied on a more unconventional approach in communicating the menace of the Sentinels, since the robots did not have highly expressive facial features. “In order to make them a little bit more intimidating we would do things like minimize the amount of key and fill on their face,” explains Pecora. “That worked particularly well in the period Super 8 and Super 16 footage of the attack, which was actually shot on period stock. The limited range in those film stocks was great because it gave us a good excuse to keep it dark and mysterious and you didn’t question when you saw it in all-CG shots where we could keep it like that to have more menacing eyes.”

Some b-roll of Beast’s attack on the Sentinels.“Then when the Beast is riding the Sentinel,” notes Percora, “you can see a lot more fill on the Sentinel’s face and he’s flailing his arms around and looking a lot more vulnerable as it’s getting beat up. Or when Magneto’s ripping apart the one Sentinel that’s coming after him, having that one eye blinking as it’s coming apart – clawing at the ground, dirt all over his face, and one eye blinking – that was about all we had to go on with facial-wise.”

The X-Men are ultimately successful in bringing the Sentinel program to an end and saving the future, although a new threat – En Sabah Nur – is revealed in a post-credits scene that foreshadows the next film in the X-Men saga. “Bryan definitely wanted this to be the biggest out of the franchise so far in terms of not just action, but visual effects,” says Richard Stammers, reflecting on the hundreds of effects shots in Days of Future Past. “Also, the fact that we’ve got the older generation of the X-Men cast and the younger generation, coming together in a fairly amazing story that has two time lines, that in itself made it an interesting story and large in scope because of that.”

Images and clips copyright © 2014 20th Century Fox.

Pingback: Future threat – X-Men: Days of Future Past | Occupy VFX!

Pingback: Superhero Bits: Batman V Superman, Netflix, Lego Batman 3, X-Men Days of Future Past, Grey Hulk | Music Movie Magic

Pingback: ภาพเบื้องหลัง X-Men: Days of Future Past | SylviaPrincesa

I have mixed feelings about the post-production quality of this show. In between some nice sequences like Quicksilver’s, you get some terrible compositing work, with spills, green reflections and bad integration. Some scenes i can recall are the Cerebro room where you see so much green spill and green reflections on Professor X’s wheelchair, or the magneto stealing his helmet one, where the metal spheres he ends up throwing at the guards are poorly integrated and feel fake.

Pingback: See what went into creating visual effects for X-MEN: DAYS OF FUTURE PAST. | X-Men Films

Pingback: “X-Men: Days of Future Past” (2014) | Kino Kults

Pingback: X-Men: Days of Future Past « Laksh Online

Pingback: X Men Days of Future Past - Technodolly Operator Q/A

Pingback: Concept-arts des sentinelles de X-Men: Days of Future Past - RedNetWork

Pingback: Quicksilver FX Breakdown

Pingback: VES Best Virtual Cinematography Award Explained

Pingback: Oscar Effects: X-Men: Days Of Future Past VFX | Digital Trends