TRON: Legacy expands on Digital Domain’s already incredibly impressive face replacement work in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. We speak in depth to 4 members of the Digital Domain team and plot the exact steps required to pull off the 165 Clu character shots in TRON: Legacy.

TRON: Legacy is a showcase for technology and some cinematic firsts: it is the first 3D movie to integrate a fully digital head and body to create the younger version of Jeff Bridges’ character; the first to make extensive use of self-illuminated costumes; the first to create molded costumes using digital sculpture exclusively, creating molds directly from computer files using CNC (Computer Numerical Cutting) technology; and the first 3D movie shot with 35mm lenses and full 35mm chip cameras (Sony F35 stereo).

TRON: Legacy is a stereo action adventure set in a digital world. Sam Flynn (Garrett Hedlund), a rebellious 27-year-old, is haunted by the mysterious disappearance of his father Kevin Flynn (Oscar winner Jeff Bridges), a man once known as the world’s leading video-game developer. When Sam investigates a strange signal sent from the abandoned Flynn’s Arcade—that could have only come from his father—he finds himself pulled into a world where Kevin has been trapped for 20 years. With the help of the fearless warrior Quorra (Olivia Wilde from TV’s House), father and son embark on a life-or-death journey across a visually stunning universe—created by Kevin himself—with a ruthless villain, Clu, who will stop at nothing to prevent their escape.

When the original TRON first came out, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences would not let the film compete for the visual effects Oscar as it used the computer and this was considered cheating. A few years on and TRON: Legacy was in post for 68 weeks after principal photography ended in July 2009. “Yeah, it’s been a while – and just for the record – we used computers on this one!,” jokes Digital Domain visual effects supervisor Eric Barba. “When I heard that about the Oscar for TRON I just realized how far we’d come.” While the filmmakers did build some elaborate sets for TRON: Legacy, so much of the film could not of course be built or made practically, and Digital Domain (DD) needed to provide most of the Tron world digitally.

Digital Domain’s role on TRON: Legacy cannot be over estimated. They prevized the entire film with director Joseph Kosinski (Joe) in stereo at their facility. “We had the art department here at Digital Domain working really closely with our modeling department as we developed and built assets and design with the art department,” says Barba. “We immediately got them into the previz, and we were really involved creatively from the very beginning so by the time we got around to planning the live shoot – which I was involved in organizing with Joe – we had figured out what we would build and what we wouldn’t need to build, where we would need to shoot stages. We did a lot of planning before we started shooting in March 2009.”

It was David Fincher who introduced DD and Eric Barba to Joseph Kosinski, when Barba was working on a Nine Inch Nails video for Fincher. “He told me about this young director he was going to bring by, and that we’d get along as he thought we had a lot in common and sure enough we got on really well,” says Fincher. The two worked together on some commercials before Barba was scheduled into The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.

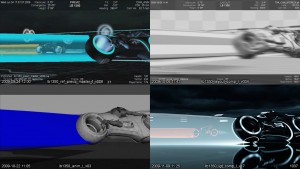

DD co-ordinated more than 1500 shots for the film, with around 800 completed by its Venice and Vancouver offices and additional contributions by Mr. X, Whiskeytree, Ollin Studio, Prana Studios and Prime Focus. At least four or five major sequences are fully CG. Of the rest there were only a very small handful that did not have a CG background or CG set extensions, and even those shots that did not have significant CG work required some sort of suit enhancements.

Much has already been written about the $60,000 practical suits and they did work and produce light on set. “There were scenes where the suits were the only light in the (dark) shots,” explains DD animation director Steve Preeg. “They definitely emitted light, but there was this desire to add to it, to put a high frequency flicker or where some of the colors weren’t exactly what Joe wanted. And there were stunt suits, or malfunctioning strips or suits that were just greenscreen tapes at points where there were meant to be lights. It was the full range of options.”

The suit lights were made of a material called Polylights, an elastomer-based, polymer flexible light. This made the lights electroluminescence flat lights. Christine Clark, the film’s associate costume designer, is quoted in Popular Mechanics as saying, “There are phosphorescent metal powders that go in part of the printing process and that’s what conducts electricity. From the first camera tests until we started building probably took us 2.5 months.”

“Still, just about every shot with a suit in the film was keyed or roto-ed for enhancement. “There is not a practical suit, I dont think, in the film that was not augmented in some way shape or form,” says Barba. “That is no slight on what was built practically – it was just the nature of the design and the look we ultimately wanted for the film. In some cases the technology was so bleeding edge you just couldn’t get these things to put out the amount of light or color that was required, but we got close.

The interesting thing about the suits is that it ultimately lead us to shooting on Master Primes (Arri lens T1.3) which gave us this really beautiful look for the film, which has a shallow depth of field.” Textbook logic would say that a stereo film should not be shot with a shallow depth of field, in much the way Avatar was shot, but DD had already shot the film by the time Avatar came out. Barba says they “didn’t know we weren’t meant to do that, but I think the shallow depth of field enhances it in many ways.”

“You know, I have been thinking about this,” adds Preeg. “In some ways, on TRON: Legacy, the shallow depth of field saved our arses, because when we first started we knew we were going to have really, really high contrast values, really bright lines against dark. We knew we were going to have it as all the concept art had it, and this is where you would normally get ghosting, you get real issues in 3D with high contrast lines like that, and I think having the shallow depth of field meant that background high contrast lines in the background get blurred back”.

It is true that in 3D TRON: Legacy had all the hallmarks of what should have been bad 3D ghosting, but the film does not suffer from this much – if at all. To the contray, the 3D stereo work on this film has universally been praised. Credit to Digital Domain but also Disney, who as a studio, has one of the best managed and most intelligently informed stereo film pipelines of any Hollywood studio.

Clu

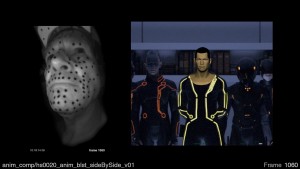

The most difficult visual effects in the film were without a doubt the character Clu, named after the programming language from the first TRON film and written as a young Jeff Bridges. It was lucky then that this film came right on the heels of Benjamin Button (2008). The 1982 Jeff Bridges is 28 years younger than the actor who won the Best Lead Actor Oscar for a broken down country singer in Crazy Heart (2009). As great an actor as Bridges no doubt is, de-aging 28 years is virtually impossible. Luckily, there is a thin space on the grid between impossible and just plain difficult. While Button had successfully aged someone, we the audience have no reference for how an old Brad Pitt will look. As Bridges has been in Oscar nominated roles many times from 1982 to the present, the audience knows what they expect to see.

Yet ironically, Digital Domain had no state of the art reference other than those same films. There was no correct lighting reference of the young Bridges, no HDRs or image probe data as it was not even invented then. In fact, even the idea of scanning someone with a laser was only a fictional reality in the actual film TRON in 1982. DD was therefore faced with a new challenge for TRON: Legacy – make someone we all think we know look like what they used to look like without the benefit of model reference or scanning technology. It was the filmmakers’ biggest technical hurdle. Speaking at SIGGRAPH 2010 in Los Angeles, Kosinski said, “I don’t think there is anything more difficult than creating a digital human that’s going to be in the same scene with other real human beings . And to top that off, it’s a digital human that people know and we must capture all the charisma and personality of Jeff Bridges.”

The process and solver used on TRON: Legacy is very similar to the Oscar winning Benjamin Button process but the acquisition and staging was quite different. One of the main reasons for changing the award winning Button process was that Jeff Bridges himself wanted to be on set acting. In the previous film, Brad Pitt was recorded much later in a isolated stage. “Jeff wanted to be on set interacting with the other actors whereas Brad was OK sitting in a chair after the edit was done,” says Barba, “so we had to rethink how we were going to acquire the data and then how we were going to use it, as the data itself was different.” The process of rebuilding the new pipeline and writing new code took DD some six to nine months of software development and experimentation.

Here’s how the head replacement process broke down.

Stage One:

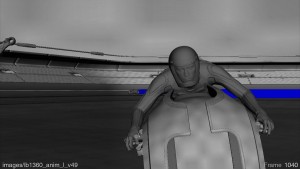

On set, Jeff Bridges wore a special rig with four black and white HD cameras provided by Vicon, feeding via a cable a custom-built logger with fully synced timecode, with four streams recorded simultaneously. Conceptually there were going to be shots where Jeff’s body would be mo-capped and DD would do a full digital body replacement (not just a head replacement), so these Vicon cameras were fitted with infra-red ring lights, so as not to interfere with the primary cameras. Body replacement was not required.

Using a 3D scan of Jeff Bridges, a mold of his face was built and from that a mask was made with 143 holes in it, acting as a stencil guide for the facial marker dots to be put on the actor’s face. These 143 dots were tracked by the four Vicon lipstick cameras attached to a carbon-fiber custom helmet, but suspended looking up at Bridges’ face, out of his eyeline so that he could see to act. “The dots were distributed so that any single dot could be seen by at least two cameras at any time for any facial performance,” explains Preeg.

Interestingly, Bridges would sometimes have to act on an unlit set with other actors blocking the shot, with only the DD team and second unit recording the whole thing with the Vicon cameras and several witness cameras (Sony 950s HDCAM). This was because first unit were not ready to move to this set yet and, while lighting current day Bridges would be helpful, it was not vital. This footage of Bridges acting with a helmet and cameras would only be used for two things, tracking and helping Bridges’ body double to re-act out the performance.

“The cameras we had on Brad Pitt (for Button) were quite frankly a bit better than what we had on Jeff (Bridges),” comments Karl Denham, sequence supervisor for the head replacement at DD. “The ones on Jeff had to be low so it was a little hard to see what was going on, especially with his eyebrows and his forehead area. And the witness cameras were not there on every single take or every single shot, and so there were times that the animators only had the headcams as their visual reference. For shots where they did have the witness cameras the animators were really happy to have them.”

Stage Two:

A 3D digital version of Bridges was created by DD using dozens of photographs of the actor in his early 30s. “We had tons of reference photos of him from all different movies,” says Denham, “but he really is a bit of a chameleon. If you look at enough pictures of Jeff Bridges, even from within one movie he looks somewhat different from shot to shot, yet alone from movie to movie. So we came up with a bit of an amalgam of Jeffs from that time period – from the period of Against All Odds, which is the period that Joseph Kosinski liked. Even his hair style was a combination of hair styles that Joe liked. The likeness issue is one of the biggest things we dealt with.”

This 3D head was re-targeted from the spatially tracked 52 facial markers from Stage One. TRON: Legacy is the first film to use the Helmet Mounted Camera in live action, allowing the actor to interact with others in the scene. The technique, as producer Sean Bailey points out, “enabled us to come up with scenes that weren’t possible. And we had a different challenge than Benjamin Button – what Brad Pitt looks like at eighty years old is speculative, but most people know what Jeff Bridges looked like when he was in Against All Odds so we had to match that. It wasn’t just technology for technology’s sake; it enabled us to write in a whole new way.”

Stage Three:

While the digital facial performance of a younger Bridges was controlled by the real Bridges performance, his body is that of John Reardon in the final shots. On set, Reardon studied Bridges and the witness camera recordings of his performance and then tried to match the movements and remain as faithful to that performance as possible.

As it is, Bridges’ voice or dialogue delivery we the audience hears was recorded during the Bridges Helmet recording. Reardon not only had to mimic Bridges’ movements but also the timing of his delivery to feed the correct timing to the other actors. Reardon’s voice is never heard by the audience but it is the only delivery the other actors heard on set. This does pose a slight problem: which take should be the hero take from Bridges? While the team mainly got this right there was no way to know on set if another take of Bridges would be preferred from a performance point of view. If it was changed then the entire Clu performance and, to a certain extent, the reaction timing of all the other actors, needed to be adjusted. For example, one dialogue shot which lasts 750 frames long ended up with 13 edits.

As it is, Bridges’ voice or dialogue delivery we the audience hears was recorded during the Bridges Helmet recording. Reardon not only had to mimic Bridges’ movements but also the timing of his delivery to feed the correct timing to the other actors. Reardon’s voice is never heard by the audience but it is the only delivery the other actors heard on set. This does pose a slight problem: which take should be the hero take from Bridges? While the team mainly got this right there was no way to know on set if another take of Bridges would be preferred from a performance point of view. If it was changed then the entire Clu performance and, to a certain extent, the reaction timing of all the other actors, needed to be adjusted. For example, one dialogue shot which lasts 750 frames long ended up with 13 edits.

Stage Four:

“Clu had to look, feel, breathe and act exactly like the young Jeff,” comments Barba. “Jeff gave us some really great performances to do that with, but it had to be a believable, realistic human, and in this case a perfect early-1980s Jeff Bridges. We took our E-motion Capture technology and pushed it far beyond anything we’ve done. It raised the bar higher than we’ve seen before.” The way the solver from DD works is that it matches a current day head scan or digital current day Jeff Bridges to his own head. “All the error metrics were all measured against Jeff at his current age, not that you would see this rig or head in the film,” says Barba.

As the young Jeff Bridges head was a completely 3D model, rendered and lit, it could be perfectly tracked to Reardon’s body, but some work was needed as it would be clearly impossible to match not only Bridges’ timing perfectly but also all the other actors’ movements and timings. DD had to retime and adjust the pacing of both the Reardon body and Bridges performance to fit in with all the other characters that were on screen with him in the shot.

Also, the re-targetting from the current Jeff Bridges to the younger Jeff Bridges is not a simple process. Firstly, the faces are different proportions since people’s noses and ears tend to be longer and bigger as they grow older, but also the point cloud data recorded from the head rig would include skin jiggle and motion induced errors that were not expression based. “To overcome this jiggle we introduced shapes into the solver that were essentially the whole face moving different directions and we would allow the solve to use those shapes to sort of stabilize the face,” says Barba. It would also help when the helmet slid or shifted on his head. So we effectively introduced false shapes into the system that were a single transform of the head. So we would see if we could get a better solve if we took out those overall movements.”

Finally, the system needed to map not directly point to point, between old and young, as much as old to underlying muscle solution to be then skinned as young Jeff Bridges. “If you look at the number of muscles that could be activating, we might have a 100 or 150 shapes we could solve to, but no real face would have a 150 muscle movements at once,” says Barba. “So our solver sort of penalizes the system for having to introduce a new shape, and so what would happen is that the rig would try and stick in tiny amounts of muscle movement but they were not really anything that Jeff was doing. What we wanted was the dominant 15 to 20 or so muscle movements in the face. The retarget process was critical to make sure it mimicked what it should and filtered out any bogus micro movement errors.”

What may seem like a simple head/facial tracking problem was anything but simple. The process of animating Jeff Bridges’ younger face was not an automated process, and to simplify the process to some automated button press is to do the DD team a great disservice. It is easy in this day and age to gloss over the process and comment as some have done in the press that ‘the computer tracked and animated on a new head’. However, as DD’s lead lighting and look-dev artist Kamy Leach says, “it would give us a good starting point. In all honesty our animators took it and then ran with it.” Denham adds that, “there were markers on Jeff’s face, but in a lot of cases the animators had to take over and make it work.”

Even if the body double’s movements were perfect, there were shots when the body double would take a breath at a different point in a speech and this could be seen as a mismatch in the body movement chest expanse and with the breathing of the mouth and dialogue that DD had to deal with.

Stage Five:

A LightStage / lightfield re-lighting session was performed on a maquette of the young Jeff Bridges that was made by Rick Baker and his company. Bridges himself was then scanned at LightStage LLC. for Flynn body doubles but those light field scans of the real actor were not used in the head replacement process. Jeff Bridges embraced the new technology on a personal level. “I love going to movies and whenever I see a big epic film where the character has aged from being a young boy to an old man, traditionally there are different actors playing him in those stages. That’s always a little bump for me as I’m sitting there, when they change from one actor to the next. But now as an actor it’s very gratifying to know that I can play myself or the character that I’m playing at any age, from an infant to an old man. That’s really exciting, especially to be part of this groundbreaking technology.”

Stage Six:

After Reardon and the other actors had been lit and performed on a set, the DD team would take detailed HDRs and lighting set references to feed into the 3D version of the young Bridges for that shot. It was therefore important that the stand-in Reardon was lit with all the hero ‘movie star’ lighting that one would want to see inherited by the digital final young Clu/Bridges.

The problem comes with how well that lighting translates from what might look good on Reardon’s face to what would look good on a young Bridges. In a perfect world, a real on set DOP would want to light Bridges and Reardon slightly differently to take advantage of each actor’s natural features and bone structures. But in TRON: Legacy, the DOP only had Reardon to light, and so the DD team would sometimes find that a slightly different digital lighting approach worked better – not mathematically but creatively – once you saw the Clu head in place.

In addition, for some scenes there were no relevant HDRs since the environment was going to be virtually added.

Stage Seven:

The look of the young Jeff Bridges, was modelled on many sources and in particular an interview he gave right after Against All Odds in 1984. The head and the new digital hair/wig were rendered and then composited into the shot with all the appropriate roto and integration using Nuke. All the hair was roto-mated and then simulated as per normal digital character work.

The digital imagery was mostly rendered in VRay. “The lighting on Benjamin Button was all very poetic but on this film the lighting was a much darker and harsher environment and that made it, I’d say, tremendously harder to light the head as you are literally shining huge amounts of very stark light on this character, in a sci-fi futuristic way,” says Denham.

“Probably one of the most challenging things,” adds Leach, “is to understand how much the human face changes form and shape when under light comes up as opposed to a top light. On Benjamin Button we dealt with a lot more soft side light, soft contrast and so forth. But if you look at anyone with a flashlight (torch) under their chin, immediately the structure of their face changes. So we came across a lot of shots where we had to still get across the look of Jeff in the younger Jeff, with this under lighting and this harsh lighting, which did not always give us that form we needed. It posed some good challenges but it definitely made it fun to work on.”

This process was the primary pipeline but as with any film there were some shots made up of additional photography or pick up shots. For these, the DD team had to add lines to a performance – essentially a talking young Bridges head to a body double Reardon that originally never spoke!

And, all of this discussion is before stereo is introduced into the mix. Tracking needs to be much more accurate when tracked for stereo compositing. “Button pushed us in regards to our tracking capabilities, to the brink of what we could do, and then we did TRON in stereo and it was ten times harder,” says Barba. “We spent a year improving our tools for Button, and then we spent another year adding to our tracking tool set for stereo.” In fact, the team from Button at DD rolled right into TRON, in fact, Barba did not even get a holiday after Button before starting work on TRON.

TRON: Legacy extends the great work that Digital Domain has done and opens the door to even more creative story telling opportunities.