When Mad Max: Fury Road was released last year, fxguide provided in-depth coverage of the film’s innovative effects work and color grading. Now the film is nominated for an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, so we’re revisiting the work with the nominees behind the impressive car chases, environments and stunt sequences. Hear from special effects supervisors Dan Oliver and Andy Williams, production visual effects supervisor Andrew Jackson and Iloura visual effects supervisor Tom Wood.

fxg: The film has been praised, of course, for its use of practical effects and stunts and what that brought to the story and the audience experience. Can you talk about how you wanted to bring that intensity for the audience to you work?

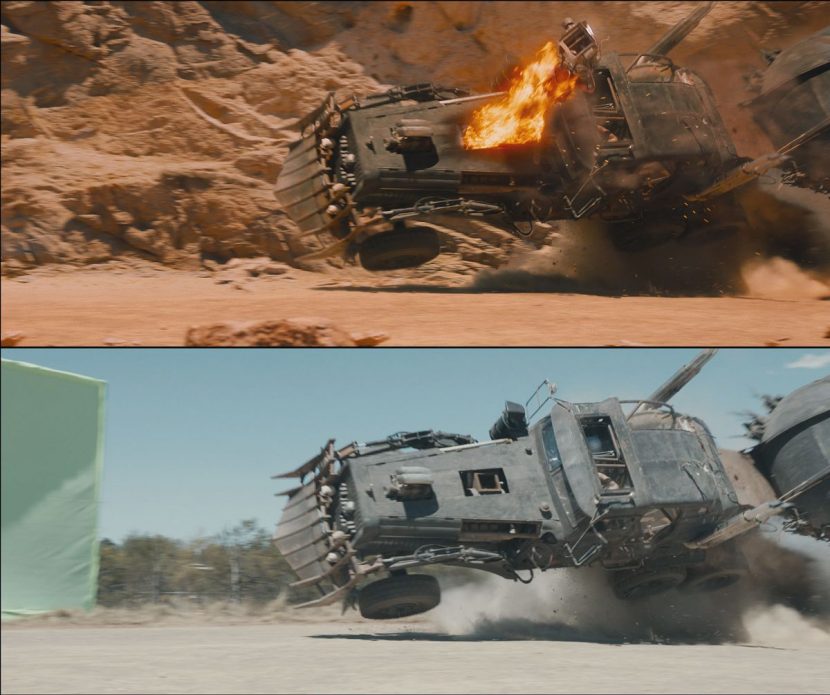

Andy Williams (special effects supervisor): It was an amazing opportunity for us as an effects team to actually take the lead in the effects and then have CGI remove rigs, cables etc. where necessary. We were always given the brief that if it’s possible do it for real then it should be. By pushing the boundaries of what could be done practically we ended up with effects that almost looked unreal, but then because the audience could tell it was real it kept their attention – as opposed to another animation. With this type of movie i.e. vehicles on the move almost constantly, it’s by far the better approach to do it for real and tidy it up in post if necessary.

fxg: Can you talk about staging some of the driving scenes – how were vehicles augmented with driving pods and other things to allow for driving and filming and the performances of the actors? Were SFX techniques also used to shoot vehicles in stationary positions?

Dan Oliver (special effects supervisor): Fury Road is 95% vehicle chase, with huge amounts of precision truck driving required. The only way to have our stars piloting these trucks while racing through the desert was to have the vehicles stunt driven from remote cells (or blind drive cell). Special Effects Department built Remote Drive cells for the War Rig, Fuel Truck, Giga Horse and Nux Car. These Drive Cells were mounted low on either side or front of the trucks. Each character truck was based on a different donor truck, so each Remote drive cell was specific to the truck type. The War rig was built over a 6-wheel drive Tatra off-road truck, running a 10-speed manual gearbox. There was no automatic option for this truck. It created quite a challenge to work this gearbox remotely. After many weeks or R&D we ended up using a series of modified pneumatic rams (running water for reduced friction) to select all gears remotely. Linear actuators with position sensors, push pull cables and Hydraulic Helm steer units were used to operate all other controls of the vehicles remotely. SFX department built 2 remote drive cells for each character truck. (There were doubles or triples of every truck). This allowed shooting crew to move straight onto a second pre-rigged truck and complete many shooting angles without waiting for SFX to re-rig the remote cell to the opposite side or front of the truck.

George Miller told us early in pre-production that he wanted to shoot in sequence, so we would need to have simtrav (Simulated Travel) available on every location. We designed a system that could be broken into small components and assembled under the trucks on the sandy Namib Desert floor. Simtrav bases used large air bags in pairs at each vehicles axle group to provide float, and bounce via fast acting pneumatic valves combined with hydraulic rams pushing in the x and y axis, this combination gave a very realistic motion capable of a very subtle sway or violent bounce and lurch. George also wanted to be able to direct action on the fly and didn’t want to wait for any programming of the simtrav rigs. So although we did have some pre-programmed moves via PLC system, SFX technicians manually controlled nearly all action. George would often call the bounces and swerves via comms or loudspeaker as we shot.

Using simple pneumatic valves and robust hydraulics proved to be very reliable in the harsh desert conditions. (Very minimal electronics to fail). The Simtrav base for War rig was assembled and used on every location and not once did it (or any of the simtrav bases) fail or cause a delay in shooting.

We built simtrav bases the War Rig, Fuel Truck, Giga Horse, Excavator truck, Doof Wagon, Big Foot monster truck, Nux car and Razor Cola. These hero character vehicles all had doubles or triples, and our bases needed to fit any vehicle. Simtrav bases were set up over 100 times during our time in Namibia.

Driving trucks through the desert created huge amounts of dust. George loved it, and told us to embrace the dust! Matching this effect for simtrav shots definitely created a challenge. We had 3 x V8 wind machines permanently mounted on Telehandlers (Grade-all) and multiple venturi rigs powered by large road compressors creating wind and introducing huge amounts of dust at high velocity.

fxg: For Max’s first big car roll, what did it take to make that possible both in terms of the car mechanics and driving and the dust that gets thrown up?

Dan Oliver: In the opening sequence where Max in his interceptor, he was being chased by an armada of bikes, buggies and trucks, we needed a spectacular crash and roll. Guy Norris (Stunt supervisor and Action Director) wanted as many rolls as possible. With all those unprotected stunt riders and drivers directly behind Max’s interceptor, the use of a Pole cannon would have been far too dangerous (the heavy pole gets ejected in the path of the chasing vehicles). So we developed what we called ‘The Flicker’. It was an arm that ran across the Interceptor chassis and hinged just behind the driver. A large bore nitrogen ram running just under 3000psi drove the arm into ground causing the car to flick into the air and roll. The arm would then retract under the chassis. We believe that this mechanism is possibly a first. Guy Norris drove this stunt himself. We achieved 7 ½ rolls on the rehearsal but unfortunately only 5 ½ on the shoot day. Looked spectacular both times, and more importantly, Guy climbed out of the wreckage smiling. The huge amount of dust thrown into the air happened naturally due to the violence of the roll on the naturally dusty Namibian Desert.

SFX did add as much light weight debris as possible into the Interceptor so it would fly into the air with the dust as the car was roiling.

fxg: Can you talk about testing and rehearsing the special effects for Fury Road? What kind of prep time did you have and did you get a chance to road-test any crashes, explosions and other effects? Are previs or miniature vehicle staging any of the methods you employ?

Dan Oliver: Fury Rd was the longest film I have ever worked on. Including pre-production, testing in Broken Hill, shooting in Namibia and Capetown and then pick ups/ final crash sequence in Sydney. Me and my core group spent 2 ½ years designing, building testing and shooting. During this time we set up, packed up and moved our workshop 6 times. George had story boarded every piece of action in the film (and also had many shots prevised), so the mechanical action required for every truck and car crash was quite specific. SFX built test trucks and cars for every flip or roll and crash in the film. Test vehicle dimensions and weight distribution needed to be as close as possible to our hero vehicles, so we could test and fine tune our methods to achieve the correct spin, flip or roll in our hero trucks/cars on shoot day. Most tests were stunt driven; the remainders were ‘tow ins’ with radio remote steering and brakes. A golden rule for our SFX team is that “Nothing goes to set without being tested”. This ensures that we don’t end up with egg on our faces and most importantly we keep all effects as safe as possible.

fxg: What were the technical specs of the main explosions in Fury Road (ie. materials, ingredients, detonation techniques)? Can you talk in particular about the spectacular cascading explosion of one of the tankers seen behind Max on a pole?

Andy Williams: The tanker explosion was a very complicated gag. The tractor unit was remote controlled, the vehicle was traveling across the desert at 50 mph surrounded by camera cars and with a camera helicopter overhead. Every step of the process was tested many times, we had mock up vehicles and tankers which we rehearsed in the desert on the move. There were many component parts to the event here is a broad list.

Fuel – 1360 litres.

Detonators – 96.

Primer cord – 280 meters 10gr.

Black powder – 5kg.

Flash powder – 2kg.

Nonell dets (non electric detonators) and cord were used everywhere to alleviate any risk from static, radio interference or other extraneous current.

It took 3 days to load the event.

Igneous remote firing system was used for non-electric ignition.

fxg: Can you talk about collaboration on this film between the special effects department and others, particularly visual effects – how do you think that helped the final film?

Andy Williams: George wanted every stunt and piece of SFX action to be prepped and rehearsed as a live action shot. Only if it was impossible to shoot safely did VFX department come to the rescue. In the end there was a mountain of VFX required- but never to completely replace live action, only for rig removal, enhancement and tie together complex and dangerous shots. Andrew Jackson (VFX Supervisor) had the same mindset as George; he knew including as much live, in camera action as possible would create the best action sequences. In my opinion the huge amount of live action and seamless CGI enhancement made Fury Rd one of the best action films ever made. There was an amazing team spirit on the project which was apparent from the first day I started work on it.

Dan Oliver: We had a very open relationship with George Miller and were always involved in meetings and discussions with him the visual effects team, Colin Gibson etc from the early stages. We also worked extremely closely with the art department and design team who were excellent as were all the crew. The tightknit crew, the easy access to all h.o.d.s. and in general a feeling within the production that we were all part of the same family most definitely contributed massively to the end result.

fxg: Andrew, as the visual effects supervisor on a film praised for both its practical and digital effects, what are your thoughts on how and why these two aspects of the filmmaking combined so well on Fury Road?

Andrew Jackson (production visual effects supervisor): There are a couple of points I’d make, one is that this film is firmly grounded in reality, all the things that happen are theoretically possible in the real world. The second point is that George was very keen to let the randomness of the real world determine, at least some of the outcome of each event. The combination of these two facts swung the decision towards practical effects wherever possible. This extremely practical approach required a similarly practical solution to the VFX and wherever possible we used filmed elements to achieve the effects. It is because the practical and VFX elements of the film are made from the same raw elements they combine so well.

fxg: You’re a hands-on supervisor with practical suggestions for making effects possible, for example with day for night, adding real elements and making that final bungey cord/steering wheel shot a reality – what do you attribute the confidence to realise shots in this way to?

Andrew Jackson: I like to base my ideas and suggestions on real world practical solutions, preferably with examples that illustrate the idea. I have a background in practical FX and building miniatures, I also grew up on a farm surrounded by tools and machinery which I think helps develop a good sense of how the physical world actually works. So if I can’t find good reference I will shoot something that helps to explain the idea.

fxg: What do you think is one effect or aspect of a shot that your teams pulled off that most people won’t realize is visual effects work?

Andrew Jackson: In talking to people who have seen the film I would have to say the canyon sequence is the one that no one realises has any VFX. The fact the canyon in virtually every shot in the journey has been made significantly taller and narrower is a big surprise. The rock towers of the citadel also seem to have a lot of people convinced they were shot in a real location.

fxg: People are still surprised about the day for night shots – were you ever tempted not to reveal the methodology behind these, and would you recommend the same process again?

Andrew Jackson: No, I’m always happy to discuss how we do things. Yes I would make the same suggestion again and next time I would have this film as an example.

fxg: In the Citadel sequences there’s a strong sense of geography and scale – how difficult was that to achieve given the way plates for that were filmed?

Tom Wood (Iloura visual effects supervisor): While each shot had been prevized or storyboarded, many of them were not shot with the scale of background ultimately wanted by George. We took each shot and crafted the composition to control light. The huge edifices of rock create light and shade so in nearly every shot we were moving the sun, or the rocks to create stripes of light, slivers of sky and deep, dark shadows to reinforce the scale and domination over the crowds that they represented. Andrew wanted to base the Citadel on real-world rock formations, and took a photogrammetry approach. He took hundreds of high-res photographs of real cliff-faces in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney, and we used images from the Jenolan Caves for the Citadel interior. At Iloura, we developed a pipeline with a variety of software to create the CG assets including Agisoft PhotoScan, ZBrush, Mudbox and Mari. Due to the photogrammetry, we had a realistic surface texture to work with which saved us an enormous amount of time in production. We did spend a good amount of time however re-working the cliff formations and geometry, re-colouring and texturing the rock formations to achieve the required look.

fxg: What was striking about the toxic storm for me was just how suddenly and more intense it became – where did you look to for reference or guidance about what kinds of things would happen in the storm?

Tom Wood: George had an idea of how he wanted the Toxic Storm sequence to develop, he described it as a ‘super-cell’, a cluster of storms within a greater storm with violent winds and twisters. He wanted a weather front with a huge dust wall to bare down on the approaching armada. Before meeting him while I was still working out of London, I used the Method concept team lead by Olivier Pron to flesh out some ideas I had for the look and content of the storm. These were shown to George and immediately became the look used in the edit room. One of the ideas we fielded was fuel burning and being sucked up into the twister – our concept twister was much more narrow so we had shown it licking right round. However George was focused on the main twister being massive, losing our perception of up, down, left and right, but still kept the fuel idea. The dark sky look inside the storm also came from the concept work, with a bright, low horizon, seemingly reachable but never getting any closer. The exterior too is a direct result of our concept art. There’s a massive pull back reveal of the Armada in the movie that sits a little out of context with the sequence. This was a single frame concept that George absolutely adored and stayed almost completely the same throughout the post period.

Reference material came from sourcing footage of real twisters and dust storms. We would sift through the footage to pick out the elements we liked and recreate them in CG. Lightning strikes were added as light sources and had a whole series of choreography passes reviewed by George to accent the action. George also specified that he wanted real-world dynamics for the shots where war boys are thrown from the vehicles, and referenced some horrific car crash videos from the web that featured real people, as well as motorcycle crashes. Interestingly, what we found was that real world motion simulations do not translate well in film language, as an audience we’re not used to seeing this kind of motion. So with George’s direction, we based our digi-doubles on real-world motion, but tweaked the movements to suit.

fxg: Can you talk about the particular tool, Mincer, that was used to help create the storm, twisters and dust clouds?

Tom Wood: Yes, our R&D team wrote this tool. It’s a particle iteration software which allowed us to run complex particle simulations through Houdini. Using Mincer we could render up to half a billion particles, still guided by the artist which gave us a huge advantage. Base smoke simulations were used for close-up shots of the twisters with layers of turbulence and collisions adding detail. Wider shots were modeled and animated by hand then converted to density volumes and level-set surface representations rendered in PRman using multi-layered procedural noise and displacement.

All images and clips copyright 2015 Warner Bros. Pictures.