We recently covered Baltasar Kormákur’s Everest here at fxguide, a stunning film with VFX led by principal vendor RVX and overseen by visual effects supervisor Daði Einarsson. But the film’s visuals were also made possible thanks to the contribution of several other VFX vendors, including One of Us in London. In this special bonus article for fxinsiders, we talk to Dominic Parker and Emmanuel Pichereau from One of Us about their work for Everest, and we feature several before and after stills of their shots.

fxg: Can you talk about the DMP work – was this something you got from the main vendor and could re-use or was it more bespoke?

Dominic Parker: A high resolution 360 degree DMP of the Himalayas as seen from the summit was supplied by RVX. But … the entire narrative rests on some characters summitting too late in the day. And the photographs which made up the DMP were all taken at the time of day when you could be at the summit and still safely descend. So we had to entirely re-light the 360 – and in fact we ended up with three versions for different times of day. Other more straightforward modifications were made – adding detail, removing clouds, etc. So, while it was very helpful to have the RVX DMP as a starting point, the end results include almost nothing of the original.

fxg: From a compositing point of view, what challenges in particular do mountainous and snow settings pose given the brightness of the white backgrounds and blue skies?

Emmanuel Pichereau: The biggest challenge for putting together the summit shots was to find the look – to find a balance of deep blue sky, readable faces, painfully bright snow (there’s a reason why they wear dark goggles) – and to bring these together in a way which was compelling and beautiful. We looked at a lot of reference photography, and this makes the problem clear. If you expose for faces, the snowscape blows out completely. If you hold on to detail in the terrain, then the sky goes a surprisingly deep shade of blue, and faces disappear into shadow. We had to find a creative balance, which of course is something of a fiction, but which we believe works.

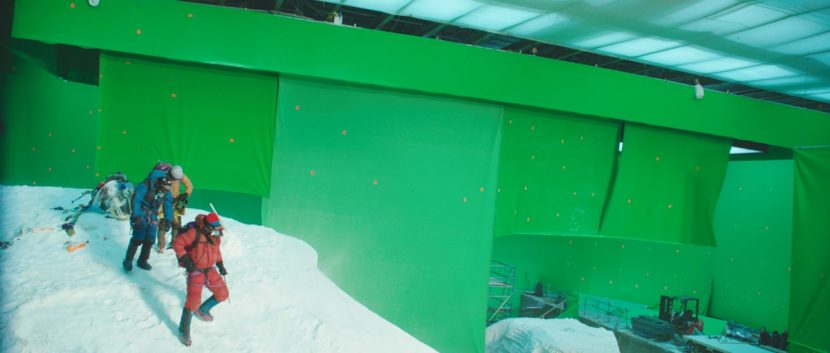

Add to this the complication that the entire summit sequence was shot on a greenscreen stage, and every time the exposure balance changed we had to re-work our edges… This project required a huge amount of re-working of shots, and this is a very difficult thing to accommodate – creatively, and in terms of schedule and budget.

fxg: What was your solution for adding ‘atmosphere’, mist and clouds into the shots? What was the right mix?

Emmanuel Pichereau: Adding atmos to the shots was an essential part of setting the scene at the summit. Reference footage has a sharpness of light, but also of atmosphere. The sun hits tiny particles of ice, and the effect is that you have fast moving layers of mist, but within this you have pings of light which are so brief that they don’t even motion blur. We spent a lot of design time finding the right balance of layers. We had a few practical elements against black, but our shots were so specific in angle and camera move and wind direction that we found it hard to use the practical stuff. And the practical elements in the plates, whilst giving a great energy to the performance, were often unusable in the comp, because they would fly off the edge of the green. So it came down to a lot of cg elements in different layers, bedded in with a few practicals.

fxg: For the storm, can you talk about your solution for the particles and ferocity of this?

Dominic Parker: The storm shots were obviously a big number for us. Looking at the wide establishing shots of the storm – at Base Camp and in the Khumbu Valley – we felt we could deal with these mostly with animated DMP. The reference we had for the storm front showed it as a lowering mass of dark cloud, but without a lot of internal turmoil. We projected DMP onto slowly developing geometry, and added layers of more particle based material on top of these. This approach worked well for these four or five establishing shots.

But the biggest shot for us was when Rob gets hit by the storm, and this shot could not be short-changed. It had to be a full cg broiling cloud rushing up the side of the mountain and hitting both climber and camera. The Director’s masterstroke was to add lighting deep in the heart of this dark cloud. This was all Houdini based atmos work, rendered through Mantra. On the shoot as the cloud reaches the climbers a burst of practical snow was thrown into the wind machine – and we added cg snow to this, so that we feel the physical impact, and we know that Rob is doomed.