fxguide was recently in Italy for the VIEW Conference, where a wealth of animation and visual effects practitioners presented on their latest work. We’ll have several fxinsider stories to come from VIEW, including this one where we sit down with ILM visual effects supervisors Ben Snow and Tim Alexander to discuss problem solving. It’s one of the key tasks of a VFX supe – take moments from the script or requests from the director that are key parts of the storytelling in the film and find a solution for how to bring it to the screen. Snow and Alexander told us about specific challenges they faced on films like Jurassic World, Age of Ultron, The Lone Ranger, Noah, Rango and the recent Star Wars Facebook 360 experience.

Getting dinos into frame

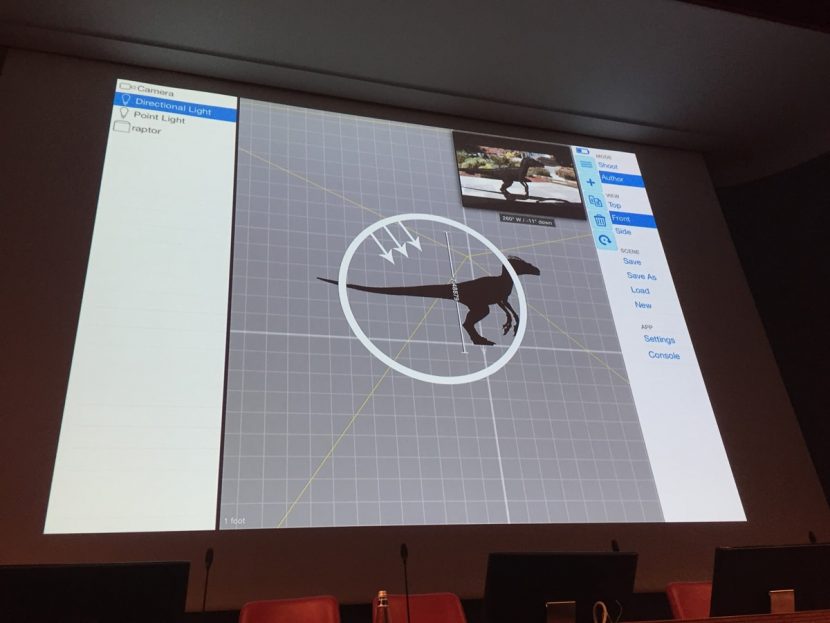

ILM has of course been part of dinosaur movies before, as well as numerous films where CG creatures are composited into live action plates. Many techniques have been used to help imagine how the final shots would look and how the plates can be framed to ensure the CG creatures will ‘fit’ in the final shots. These include previs, stand-ins and cardboard cut-outs – all of which were still used on Jurassic World. But a new way to solve the problem came in the form of ILM’s Cineview iPad app, as visual effects supervisor Tim Alexander explains:

We created Cineview for Jurassic World and now it’s being used by many supes on different shows. It really saved our hides a number of times to get the framing right for the dinosaurs. It’s all standalone, that’s the main idea. You can put your assets into it, which are kind of video-game versions, but not terrible quality. They can be the previs models or ones that we’ve been modeling – they can be an OBJ with textures, basically. You import that into the library and you have that in there and it’s very Maya-like where you can put the assets out into space, set a ground plane, have shadows and basic lighting.

In the version I had for Jurassic it was just pan/tilt but it was lens accurate. I could stand next to the camera and plug in what lens package we’ve got and what camera we’re on and then you can dial in a 35mm and put in a dinosaur and from that you could work out if you have to tilt up or move the camera – and we’d make changes on the spot if we needed to. It wasn’t super-complicated but it got everyone in the right space.

We even used Cineview to cast the guys who would be playing the baby triceratops that the kids ride in the petting zoo. We hired these big Hawaiian police officers who were 6″ 5′ and put a saddle on them and the kids rode on their back. I had the baby triceratops on the app and this guy on his hands and knees and I could see if the guy was going to be the right height.

Since then, we’ve integrated the Structure Sensor which can be easily fitted to the iPad, and with its depth sensor it makes things translational so I can walk around the dinosaur, as long as the environment’s good for tracking. I think this kind of thing will replace the need for a simulcam – you’ll be able to take your iPad out and do the same thing.

In the version I had the dinosaurs were static, but we’ve just implemented another thing – we’re calling them Beacons – you have say an iPhone with a GPS on it and you go out and be the dinosaur and you carry the Beacon with you. You go out to the forest and walk around and the dinosaur will also walk. That means we can have multiple sessions that aren’t connected to each other but they all see the same object, so you can see it from different angles. That means multiple camera operators can each have an iPad and see the dinosaur moving out there.

The Force Awakens in 360

In September, Facebook announced that 360-degree videos would begin being available to see in its News Feed. One of the first videos was a desert ride along a speeder within the Star Wars universe, a tie-in to the release of The Force Awakens later this year. The video was crafted by ILM’s new ILMxLAB which has been behind several VR and immersive experiences. ILM visual effects supervisor Ben Snow oversaw the work, but first he had to consider how to give a hint of world and how to make it immersive, as he relates to fxguide:

In September, Facebook announced that 360-degree videos would begin being available to see in its News Feed. One of the first videos was a desert ride along a speeder within the Star Wars universe, a tie-in to the release of The Force Awakens later this year. The video was crafted by ILM’s new ILMxLAB which has been behind several VR and immersive experiences. ILM visual effects supervisor Ben Snow oversaw the work, but first he had to consider how to give a hint of world and how to make it immersive, as he relates to fxguide:

We had a very limited time frame and essentially what they wanted to do was a make 360 interactive video experience that you could pan around on Facebook. I was really interested in VR and immersive things – this actually isn’t a VR project, but we do have the xLAB now at ILM. It’s funny, I had been trying to avoid knowing anything about Star Wars! But I had to go through all the footage and materials they had and try to find something that I felt could be compelling and be different from the movie. Something that would really exploit the 360 viewpoint.

Star Wars: The Force Awakens Immersive 360 ExperienceSpeed across the Jakku desert from Star Wars: The Force Awakens with this immersive 360 experience created exclusively for Facebook.

Posted by Star Wars on Wednesday, September 23, 2015

At SIGGRAPH, USC had an open house and that meant I had a great bootcamp on VR, plus the xLAB team here is doing some amazing things. Not knowing everything about VR and immersive tech was an advantage in some ways because I could go in there and break the rules. We’re going to put the camera on a moving vehicle. Some of the VR experts I spoke to said there had been all these studies that in VR you need to see the horizon line. We were on the speeder bike so we played with the idea that if it was stable to you, you wouldn’t feel so disorientated.

We had to find something that we could pretty quickly get up to speed to make into a 360 experience, and that would involve looking through everything Star Wars was doing and adapting it into 360. That was a soup to nuts problem, but those are the most fun sometimes. We were worried and conscious of the horizon line issue. The first version was quite smooth and we showed it to JJ Abrams and he said he wished the bike went up and down a little bit more and followed the terrain. It was a 360 video, and not VR specifically. But we did get a couple of the guys from Disney Interactive who have done lots of ride films, and they were fine with adding in a little more undulation.

‘We’re going to need a bigger environment’

On The Lone Ranger, the film’s signature end sequence required a two train-horse-desert-mountains-forest pursuit that had to look photoreal. During planning and shooting, Tim Alexander quickly realized ILM would need a new solution for these complex environments:

On The Lone Ranger, the film’s signature end sequence required a two train-horse-desert-mountains-forest pursuit that had to look photoreal. During planning and shooting, Tim Alexander quickly realized ILM would need a new solution for these complex environments:

Our biggest issue to solve were the photorealistic environments and then also modifying the environments that were in there. Before we started the movie, that end sequence presented itself as the biggest hurdle. Gore Verbinski (the director) and I had made this 50 per cent rule – we were always going to try and get half the shots in-camera no matter what we do. But we did need a lot of CG for this sequence – there was no other way to do it, because we had to get two trains next to each other. We actually looked for locations where it might be possible. First of all, trains don’t go as fast as you want them to go in America, and you just can’t find a location like Gore had in his previs. He really designed that whole sequence with the music all beat out and we ended up producing something very close to that previs. It was very specific about where one train was in frame compared to the other train in the frame.

While we were shooting we knew this would be our biggest issue. I kept calling back and telling the guys, these environments are going to be big! We had to replace the road we were driving on anyway. We did do some tests, but what we did was sit down with our TD supes and modeling supes and our generalist team and say this is our problem, who wants to take it? On that show it was decided that the generalists and digimatte team was the best way to go, and that supe (Dan Wheaton) went off and started spec’ing how everything was going to be done. Giles Hancock also did some early work on it as well. We went to V-Ray for the trees and environments because we found we had to go deeper and deeper into the environment and we couldn’t just use cards.

An even more believable Hulk

ILM had tackled Hulk a couple of times before his appearance in Age of Ultron. By then, the VFX studio was heavily invested in its creature pipeline, certainly, but the character still needed more – more believability, more realistic muscle and skin sliding. Ben Snow set out to solve that problem early on in production:

ILM had tackled Hulk a couple of times before his appearance in Age of Ultron. By then, the VFX studio was heavily invested in its creature pipeline, certainly, but the character still needed more – more believability, more realistic muscle and skin sliding. Ben Snow set out to solve that problem early on in production:

Hulk hadn’t actually worked for me as a character until the first Avengers. I thought they had done a great job and it was a great starting point. One of the problems they had on that film was that they had to do a lot of corrective shape work. The animation would take place and then it would be put through creature and simulation and Hulk would end up looking quite different. So they had to do a lot of hand work and they would drift off-model and the modelers would be there for all hours to fix it.

So we thought this was an important thing to solve. We put a lot of work into the muscle system so we wouldn’t have to do all that extra work. But it wasn’t just an efficiency gain, it was also about him staying on-model. And we had better looking muscle sliding underneath the skin. It solved several problems – production and creative.

So we thought this was an important thing to solve. We put a lot of work into the muscle system so we wouldn’t have to do all that extra work. But it wasn’t just an efficiency gain, it was also about him staying on-model. And we had better looking muscle sliding underneath the skin. It solved several problems – production and creative.

It was basically one of the first conversations I had with Christopher Townsend (the overall visual effects supervisor). We had lunch down in LA and he was feeling me out because he didn’t want the answer, ‘Oh we think Hulk’s great and he’s perfect,’ but I thought we could improve the work. He’d actually been involved in Ang Lee’s many years ago so he was aware of some of the challenges.

Tackling an animated feature

Rango was ILM’s first animated feature, but previously the VFX studio had been exactly that: a VFX studio. That meant a new thinking in terms of pipeline and workflow, something Tim Alexander tackled head on:

Rango was ILM’s first animated feature, but previously the VFX studio had been exactly that: a VFX studio. That meant a new thinking in terms of pipeline and workflow, something Tim Alexander tackled head on:

Our biggest challenge on Rango was pipeline, and keeping ourselves from a ‘keep everything alive for the whole length of the shot because everything’s going to change at the last minute’ which we do in VFX and try to get ourselves into an animation pipeline. We did a lot of research and talked to a lot of people in animation, and we knew our VFX side. The mental part of it was separating the pipeline after animation and what we were calling final layout and going into lighting and all the stuff past that and actually making a strong break point there. And closing out a whole sequence in animation and in final layout. And say, OK, now we’re going to throw that over the wall to lighting, we’re not going to go back. That was a big change for us, but also something the director Gore had to buy into as well. It was a very big mental hurdle for everybody to do that.

We were having a lot of problems at the beginning because our layout pipeline wasn’t designed to move a whole bunch of set dressing around and have that stick. We hadn’t really done a lot of set dressing, it had also been done in the digimatte realm previously. What that allowed us to do is – we did something called pre-flight which was we had a non-senior lighting person, say an assistant technical director, go in and do the first lighting pass on the whole sequence. The whole sequence was packaged up at that point and included set dressing and final cameras. This person would actually go in and do a first lighting pass on the whole sequence, and me or John Knoll would brief them and say this sequence is about – it’s supposed to look hot, so let’s bring the sun a little further forward and let’s give them a quick rundown.

Creating creation

Darren Aronofsky’s Noah presented many, many challenges to ILM, not the least of which were shots showing animals entering the ark, and a sequence that revealed the creation of the universe and of animals themselves. For these, ILM had to solve design issues, shoot background plates and work on an efficient way to model, rig and texture so many animals, as Ben Snow explains:

I was scared to death of the creation sequence. Originally ILM wasn’t going to do that sequence. The guys who did the previs were going to execute the sequence. We had done a lot of planning and some tests and then these other guys were going to do the sequence. Darren’s concern was that he wanted it to be as realistic as it could and he wanted to use some photographic components. There had been some exploration done for how photographically it would work and it was pretty effective, especially because it was a more ethereal and abstract thing.

I wrote down a plan and said here’s how each of these sequences is going to be approached. I hadn’t realized it, but I had been thinking a lot about how we were going to do this. I said I would get one of my colleagues, Grady Cofer, to go out and shoot the plates in Iceland and see the sequence through. By that stage we were so heavy into production with the rest of the film.

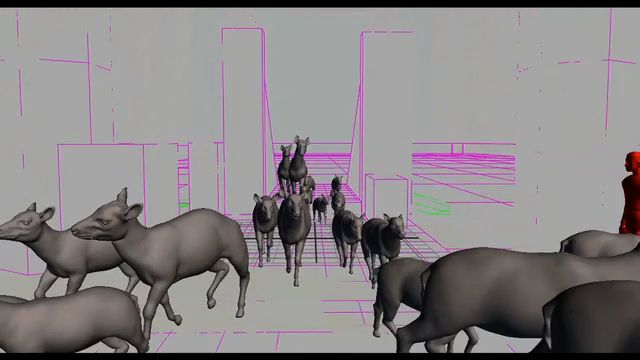

We had developed a new approach to rigging for making animals with our BlockParty 2, originally for the ‘entering the ark’ shots. We were concentrating originally on those shots being a big herd of animals. But in the end they were much closer to camera shots and there was a huge variety of animals – hundreds of different types. The way we approached it was – I asked, is there a way we can make the animals in parts to create this ‘Zoo’ – we had eight fundamental animal shapes and the model supervisor came up with an approach where he could make those into components and it was really clever the way he could mix and match all these things to make a huge variety of animals. They shared a topology and then we could transport textures. So you could paint a Tasmanian Tiger type texture and have that applied to very different types of animals. That meant we could really create an infinite variety which is what we needed to do in an efficient time.

But it also meant we could work out ways to make the same rig be transportable – we wanted to take animation and apply it to so many different animal shapes. Then all of that planning and thinking went into the creation sequence. We did some great research and we hired a grad student and he researched what would be the timeline from amoeba through to ape and tried to make a timeline for that. I then put that timeline and had the different animals for so many seconds each. Then we took the zoo kit we’d created and built the creature that could evolve before your eyes. That, combined with the terrific backgrounds, made for what I think was a really unique sequence.