Kim White was the director of photography (lighting) at Pixar on Inside Out, which is just on DVD and Blu-Ray. Recently at the VIEW Conference in Italy she outlined Pixar’s process for how the studio approached lighting in the film. fxguide then spoke to White afterwards about the dinner table scene in which Riley appears grumpy – at this point inside Riley’s mind Joy and Sadness have ventured into unknown territory leaving just Anger, Fear and Disgust behind.

https://youtu.be/HVoi6HHA92M

fxg: Can you set the scene for this dinner table conversation?

White: It’s after Riley has had her bad day at school. There’s color in it but it’s heavily saturated. It’s also evening, so we’re using that light from above. You never actually see the lightbulb of the main light because we thought it was distracting, but they don’t at this point have a shade – so it’s pretty strong lighting from above. Even so, you don’t want it to be harsh on the characters, you still want them to be appealing. It’s not meant to be an interrogation sequence.

So what I love because we have that light from above is that we can have darker areas behind the characters, such as in the kitchen and out in the entry area. You get these nice looking characters in the foreground and then darker in the background, which gives it a visual complexity.

fxg: How do you visualize the lighting?

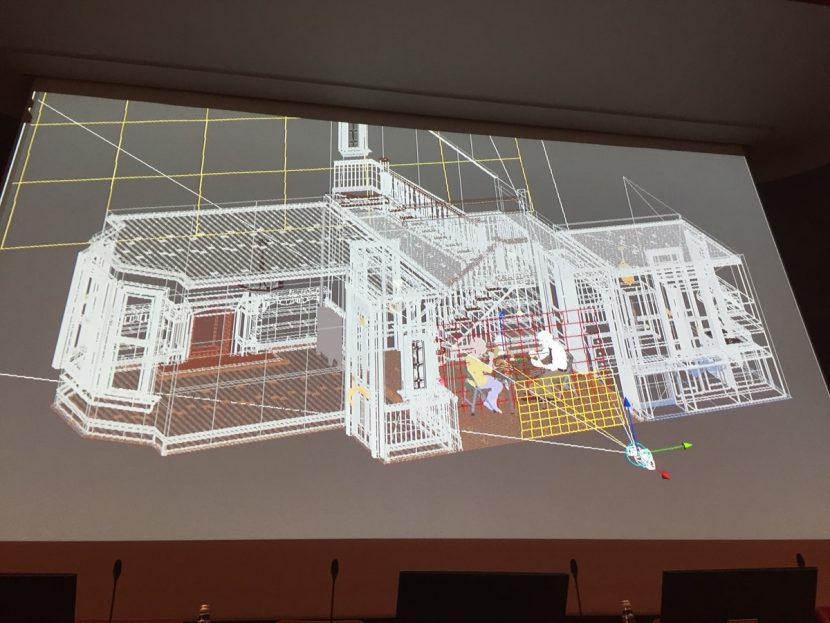

White: Ultimately you’ll want to do a render, but we do have tools that can calculate the lighting very quickly – it’s not realtime, although we’re all looking to that day! But it’s very quick and it caches a lot of the aspects in the scene and knows what you’ve moved, so that it can only render that and give you feedback very quickly. That helps a lot because you’re iterating a lot of things all the time.

fxg: How long do you have to do the lighting for a scene, typically?

White: Typically a sequence like the dinner table sequence you would lock in the master lighting which could take anywhere from a week to four weeks. They block in the main lights, and the shot lighters take the lights. If you’re looking at Mom, that might take three days to get it crafted right. There’s many shots of her at that angle, which means you could plug in the same lighting to different shots and tweak the little things that don’t quite work.

Then if you have another shot that’s further back and has all the characters and the whole set, that can take a couple of weeks to nail down since there’s so much going on. The shots of Riley were harder than of Mom and Dad because she’s looking down. That would take a lot of work, because it would get dark and it would look like she had a beard! So we had to cheat the lights and find the balance to make her appealing and well-shaped. That takes more time.

The lighters learn the characters and the visual goals of the movie. Which means earlier in production we’re slower but by the time we get to the end of the film we’re a lot faster.

fxg: What is the review process for lighting a shot like this?

White: Early on, Ralph Eggleston the production designer and I would look at the sequence without any lighting, and I would say to him, say, ‘For me to direct the lighters, it would be fabulous to have this wide point of view and maybe this shot,’ and then he’d suggest shots too. Then we would make the color keys and show them to the director. I’d be there too and he would add his comments.

We then take everything and I direct the master lighter based on the color keys. Then once we get in there we might say, Oh let’s make this a little bit warmer, or cooler, or shift the colors. For the most part you’re using the lighting color keys as your guide. At this point we’re not working on every shot – just a couple.

Once we get it to a place where we think we have what we need to go into shot lighting, we call on the director to come and meet. On Inside Out, I liked to have Pete Docter there, the master lighter there and Ralph there. We would meet and say to Pete, we’re going to go into shot lighting, do you feel good about this? And he would give the all clear and might have any notes.

Then we distribute the shots to the shot lighters. You might give all the shots of Mom to one person and all the shots of Riley to another – you break them up to the groups that make sense. Sometimes if you’re lucky you’ll get all the shots to light from one sequence – Abstract Thought was one of those. The same master lighter lit all those shots, which I love because they have ownership of the sequence, they work quickly because they understand the sequence. But it’s often not like that simply because of time.

The shot lighters would then start lighting, and they come to see me every day or every couple of days. The goal might be to get say two particular shots done by the end of the week. I’ll give them direction as they’re going along. When the shot looks good I final it.

At the end of the week or beginning of the next week, I’ll show Pete all of the shots that I finaled. Depending on where we are in production, that could be 10 shots or 100 shots. As we go along, and things get done, our quotes get much bigger. The idea there is hopefully Pete is not going to give us too many notes. Me finaling shots is to save everybody time. He might have a couple of notes, and they go back and get worked on until being finaled.

I watch everything in continuity so I see the shots with the other surrounding shots. As we’re working on a sequence I’ll take time to look at the entire sequence. At a certain point when we think a substantial amount of it is done, we’ll get the main leads from the other departments together with the director and the production designer and we’ll look at that sequence on the big screen. At that point they are looking at everything – animation, effects – not just lighting. Does the sequence flow? Is there continuity?

fxg: You said in your talk that although you try and light realistically, sometimes it’s about cheating the lighting, too, to hit the right emotions.

White: The first pass on it isn’t necessarily about reality. You might have some lights that don’t actually do what they would normally do. But you’re working from broad to fine. So in an ideal world your lighting is as simple as you can make it, so that it renders faster and if someone else has to take over a shot they can understand. When it gets too complicated you can kind of see it in the image. Things aren’t adding up properly.

So you do want to keep it simple. The idea is that we start with the broad strokes. It’s not necessarily reality, but it’s the reality of the original goals in the color key that we’re going for. Then we refine it from there. It’s also all constructed anyway, even if you’re using global illumination – you’re still constructing the image. What I do is look at it and say, is it believable to the viewer? Would the viewer see that and trip up on it? Are they looking where I need them to look and conveying what I need to convey?

It’s also based on how we want the audience to feel. For Riley, we really want the audience to feel for her, because she really for a time turns into an obnoxious pre-teen. So whenever you light her, you need her to be cute and vulnerable. You cheats on Riley, not just for her shaping but to make sure that she looks that way. You don’t want the audience to go, good riddance! On Toy Story 3, as well, Bonnie always needed to look as cute as we could possibly make her because we wanted the audience to feel OK about the toys going to live with her.

fxg: There’s a lot of subtle work involved in making the audience read these characters and emotions, do you ever get worried people won’t notice?

White: Yes, I even just got asked by someone, why are spending all this time on the lighting, is anyone even going to notice? But I said to them, here’s the deal: when you watch The Godfather, that’s an ‘A’ film – the story is amazing, the visuals are too. A lot of audience members can’t tell you why, they just know it’s beautiful. It’s manipulating you emotionally. That’s an A movie. So we want to make A movies, why would we want to make a B movie? Without that care taken to lighting, you might not have that extra complexity of emotion.

I remember a scene from A Bug’s Life that really hit this point home with lighting. The grasshoppers decide to come back to Ant Island and they’re flying back and they light them with this sunrise or sunset lighting – it’s really, really colorful. But then when you cut to the shots of Ant Island it’s really gray and fogged over. But by making those grasshopper shots really saturated, when you cut to Ant Island it feels even more gray. So I realized it’s not even about the individual shot, it’s how they cut together. It makes you feel even more scared and anxious. I thought that is the coolest thing ever that this can be done with lighting!

All images and clips copyright © 2005 Disney/Pixar.