Feature films produced using Linux include Star Wars Attack of the Clones, Lord of the Rings 2, Star Trek Nemesis, Harry Potter, Scooby-Doo and many more. Every major studio has converted to Linux or has a Linux conversion underway. Linux has become the most popular operating system for feature film production. But with no Adobe Linux version of Photoshop, – the most popular open source Linux application in the post industry is now Film GIMP (or it was …

Film Gimp has changed its name to CinePaint, which marks the coming of age of this program, and its recognition as an important separate program from the main original GIMP image editor. ( And lets face it after Pulp Fiction isn’t GIMP just about the worse name for a product in the history of post !)

Linux started it move into the visual effects production pipeline over 5 years ago. In 1998 for example Daryll Strauss at Digital Domain used a wall of Linux servers to help render some of the computer intensive water scenes in the Academy Award winning Titanic. Linux’s use quickly spread from servers to workstations as key vendors started porting their applications to the widely growing operating system.

One of the first vendors to port to Linux was SideFx software and its Houdini 3D animation system but the real fun began when the Visual Effects Society organized a summit where 24 of its members companies met and jointly asked the vendor community to port to Linux. In 2000 when the summit was held only a hand full of programs ran on Linux. Today every major equipment supplier has an active Linux solution or at least a private Linux strategy –except Adobe. The use of the operating system has moved from render-farms to desktop solutions with Maya, Softimage, Discreet, Shake, Nuke, Renderman, Kaydara, US Animations, and SGI all withLinux solutions. Linux has now become the number one operating system in Hollywood. More popular than Windows, Macintosh, or SGI’s IRIX. There are 300 Linux desktop systems at Dreamworks alone. Digital Domain has now used Linux in 21 motion pictures, and has won two technical achievement awards one for Track and the other for NUKE, both run on Linux. But perhaps the most noticed industry move was when ILM switched its animation department to Linux. Rob Coleman, ILM’s famous lead animation director from Star Wars commented recently in Sydney, ” I am normally against switching platforms or software versions, but we switched over completely in mid project ( of Star Wars Ep 2)” Coleman went on to point out that it was the pure speed improvement that the animators gained that convinced him the move was the right thing to do, even with – or because of – the huge task ILM faced on Ep2.

One of the major areas left unresolved in the Linux world is Adobe’s Photoshop. The IRIX version of the program (version 3) long ago fell behind in releases and Photoshop is one of the most universally loved graphics programs, from 3D textures to digital matte paintings, Photoshop is used and loved.

Enter GIMP and the film version : Film GIMP.

GIMP began as a class project by two students at the University of California Berkeley in 1995. Film GIMP started as a break away from the GIMP project around 1988. Originally it was developed as an open source paint program to companion to Silicon Grail’s Chalice Compositor. CinePaint can be thought of as a Linux Photoshop – but designed for frame sequences rather than layers of a single frame and absolutely critically it runs at 48 bit rgb, ( 16 bit colour depth) rather than just the 8 bit colour that GIMP supports. Actually the so called ‘Hollywood group’ did not intend to break away from GIMP, but its enhancements and suggestions were shunned by the core GIMP developers, unfortunately this left a bad taste in the industry’s collective mouth, as Pixar’s Vice President of Technology, Darwin Peachey commented in Linux Journal, Feb last year “Extensions were done by the VFX industry but weren’t picked up by the project. This left some members of the industry feeling that because we’re a market segment different than what open-source developers are interested in, the industry can’t get any open-source developer seriously interested in what the industry needs”

After the rejection from the GIMP project team, Silicon Grail dropped its sponsorship, (and two years later they were bought by Apple anyway !), things looked bleak for Film Gimp, but the project wouldn’t die and was still being used ‘underground’, in production, at Rhythm & Hues. From there it spread to Sony Pictures Imageworks (SPI). At the time most thought that Film Gimp was dead, including Robin Rowe – writer and software developer, – now CinePaint’s project leader Rowe recalls, “for my column at Linux Journal I wrote a story about Film Gimp. Film Gimp was always obscure. It was believed extinct. Discovering that it was in use in Harry Potter was a bit like finding a live sabretooth tiger.

The mail I got asking me questions about it urged me to delve deeper, and I wrote a second Film Gimp article for Scooby-Doo. Everyone was turning to me for Film Gimp information because they couldn’t gain access to the studio developers. There had never been a public release of Film Gimp, and nobody wanted the job of supporting it. I became release manager.”

Since launching on SourceForge on July 4, 2002, the Film Gimp/CinePaint project has made 16 public releases, averaging two releases per month. That’s a remarkable rate of progress. It has advanced from being used at three movie studios to four (Rhythm & Hues, Sony Pictures Imageworks, Hammerhead, and ComputerCafe), and has grown from just a few developers to more than a dozen. That’s a lot to have accomplished in eight months.

CinePaint is now the most popular open source tool in the motion picture industry, but ironically, comments Rowe, CinePaint is not behind the switch to Linux. “It is the most popular open source tool in the motion picture industry, but not a driver for Linux. Actually, it’s the other way around. That Photoshop doesn’t run on Linux compels studios to consider CinePaint. What is enabling Linux on the desktop is powerful graphics drivers from companies like NVIDIA. What is driving studios to consider Linux is retiring SGI IRIX workstations. ILM has observed a 5x performance boost in switching to PC Linux workstations. In Hollywood speed is everything, and that’s what’s driving Linux.”

The remarkable color range of CinePaint appeals to 35mm cinematographers and photographers because film scanners are capable of more color bit-depth than can be displayed on a monitor. CinePaint supports many file formats, both conventional formats such as JPEG, PNG, TIFF, and TGA images — and more importantly cinema formats such as Cineon and OpenEXR. It is a general purpose tool useful for print and the Web, but it is firmly focused on the motion picture industry.

Coming in 2003 is import/export of popular video formats. That will include DV, MPEG, AVI, and Quicktime. Motion picture users work with directories of images, but converting to video files will make CinePaint useful for video editors, too. This feature is a plug-in, not integration of video editing like, say, an Avid or FCP offline editor. Rowe is also planning a plug-in for browse editing. “This is very quick news-style cutting, unlike the typical Avid or Premiere finish editor. I have a background in television news. I built a browse editor used at news station Time Warner New York One. Years ago I was an NBC-TV technical director”.

CinePaint is used for a lot of retouching, but it is only now just starting to appeal to matte painters. Rowe comments that “the GUI overhaul will help. CinePaint requires too much mousing and clicking in common painting tasks. They ( matte painters) also need macros. The next enhancement is improving how layers work”.

Some ‘stills’ features are also coming. CinePaint also intends to expand outside the motion picture space. Menus are being added to offer easy access to darkroom-style operations, somewhat along the lines of Photoshop Elements. CinePaint has announced some sort of CMYK support coming in 2003.

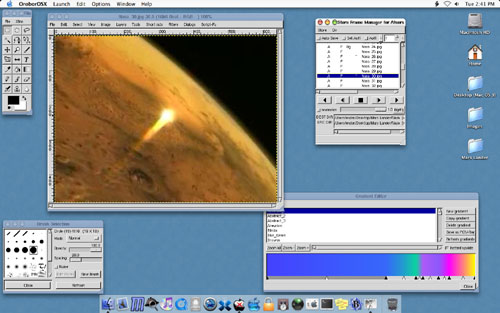

And it is expanding out of just the Linux space. The Mac OS X version has now been released. but an objection from Mac users is that CinePaint is running on Mac/XDarwin, rather than being a true Mac/Aqua app. XDarwin is an X Server, and running that layer is extra complexity for Mac users. There is a popular tool called Fink that manages a lot of that complexity, but it isn’t as simple as running on Aqua directly.

CinePaint Mac port lead Andy Prock and Rowe began researching ways to make Film Gimp into an Aqua app as soon as the XDarwin version was released. “The reason Film Gimp Aqua is hard is that GTK+, the GUI that Film Gimp uses, doesn’t have a native Mac port. On Windows there is one, but not for Mac. We looked at other GUI libraries such as FLTK that support cross-platform, but it looked to be a lot of work to make a toolkit change. Andy discovered an abandoned incomplete OS 9 GTK+ port, and researched bringing that back to life as an OS X project”, explains Rowe. Two weeks later, on New Year’s Eve they launched the GTK+OSX project and their first release of GTK+ for Mac OS X. Development moved very fast. “GTK+OSX is a separate project because it can bring not only CinePaint but the rest of the Linux GTK+ and GNOME apps over to Mac Aqua. There’s tremendous interest in that. Our announcement generated record traffic at OSXFAQ.com” points out Rowe. The CinePaint web site predicts the Aqua Max OSX version as coming June 2003.

Even with all its popularity and success for far, some people are still surprised to hear that the current software release of CinePaint is still a pre release version ! Rowe points out the project is far from finished, “The GUI is the main thing holding us back now. The goal for 2003 is to make the GUI in CinePaint better than that in Photoshop. I’ve been itching to work on the CinePaint interface from day one, but infrastructure, stability, and cross-platform have had to come first. ”

“We’re also going to declare version 1.0 sometime soon !” jokes Rowe.