In this interview, DNEG VFX Supervisor Jelmer Boskma offers a comprehensive behind-the-scenes look at the visual effects for Murderbot Season 1, emphasizing the importance of early previs and techvis in shaping key action sequences, most notably the dramatic “Worm Attack” in Episode 1. He explains how previs, creature design, and environmental planning worked in tandem to support both storytelling and technical execution, allowing for better stunt planning and photoreal CG integration.

A standout technical challenge was the deployment of Murderbot’s CG helmet, which involved reverse engineering, physical and digital tracking, and subtle post-production details (like an “ear wiggle”) to enhance realism. The team also created richly detailed digidoubles and developed multiple CG models of the alien worm to depict various stages of battle damage, enabling flexible but grounded storytelling in both fast-paced and emotionally resonant scenes.

Boskma details the FX pipeline across sequences involving dense creature interactions, complex lighting conditions, and large-scale CG environments. From managing dust, gore, and weapon fire through layered simulations, to matching weather inconsistencies with cloud shadows and matte paintings, the team aimed for seamless integration of visual effects into real-world footage.

Notably, Murderbot’s emotional arc was a guiding principle in animation and compositing decisions. Even subtle shots, like a CG-enhanced walk toward the Preservation AUX habitat, were fine-tuned to reflect the character’s unique blend of stoicism and awkward empathy. Boskma praises the collaboration between departments and highlights the artistry in invisible effects—those that go unnoticed but deepen the show’s immersive world. For him, the quiet realism of extended habitats or enhanced spacecraft was as satisfying as the spectacle of worm attacks, a testament to the team’s commitment to cinematic worldbuilding with restraint and precision.

Jelmer Boskma is an Emmy and VES Award-nominated visual effects supervisor and art director with a passion for cinematic storytelling and visual worldbuilding. He a VFX supervisor at DNEG, where he leads the creative and technical execution of effects from pre-production through final delivery, including on-set supervision. Jelmer began his career in digital sculpting and creature design, later expanding into matte painting, concept art, and art direction, all of which informed the great work on Murderbot.

Interview with Jelmer Boskma, VFX supervisor, DNEG

fxguide: You joined Murderbot right from pre-production, can you talk about how early previs and techvis helped shape the tone and scale of the action sequences? Were there any particular sequences where previs meaningfully influenced shooting decisions?

Jelmer Boskma: DNEG’s 360 Previs team was brought on early to help flesh out the ‘Worm Attack’ sequence in Episode 1. Working closely with Production Supervisor Sean Faden, our team, led by Previs Supervisor Pablo Plaisted, developed the sequence from the ground up. Since the scene was packed with action and complex stunt work, having time during prep to explore the blocking and shooting methodology was invaluable.

The script called for extensive physical interaction between Murderbot and the Female Hostile, the worm, including a significant portion set inside the creature’s throat. As Pablo and his team refined the scene’s blocking, Sean and I were able to identify some of the key challenges we would face in terms of photography and CG integration. Much of our early discussion focused on how to approach lighting for both Murderbot and the two other characters in a way that would feel grounded and coherent once the CG elements were added.

fxguide: Murderbot’s suit is a recurring centerpiece. How did you design the deployable helmet such that it tracked and matched the actor’s face, and if it had been real… and is it accurate in the sense that the actor’s head could easily fit inside when closed, or is it actually smaller than a real helmet would need to be?

Jelmer Boskma: Multiple physical helmets, with varying degrees of damage and wear, were fabricated by the costume department for Alexander to wear on set. The design allowed him to remove the faceplate as a single piece, but we wanted to explore something more dynamic. We looked into a more mechanical approach to the helmet’s deployment and retraction, aiming for something that felt grounded and functional.

This process was very much a case of reverse engineering and trial and error. We began by identifying natural cut lines in the existing helmet design, then gradually broke it into sections. From there, we blocked out a rough animation to experiment with how the pieces could move. It became a time-consuming puzzle for our modelling team, since we wanted to avoid visually cheating the scale of any components. Along with slicing up the outer shell, we added internal mechanical detail that only becomes visible as the helmet activates.

For shots that required the helmet to deploy or retract, we filmed Alexander both with and without the physical helmet. The practical piece fits snugly and actually compresses his ears slightly. I pitched the idea of adding a little ear “wiggle” in post to help sell the moment when the helmet clears his ears and they pop back into place. We also added a subtle bounce to his hair as it lifts once the helmet pressure is gone.

To ensure a seamless integration of the CG helmet, we body-tracked Alexander from the shoulders up using a 3D digi-double. This not only gave us a precise match for animation, but also allowed us to render shadow and occlusion passes that we could composite back into the plate for a more believable final result.

fxguide: The worm attack scenes are intense, layered, and quite visceral. Can you walk us through the creature FX pipeline, particularly the integration of digidoubles, gore elements, dust, and CG set extensions? Was all the blocking solved in previz to keep all the geography of the action legible?

Jelmer Boskma: Let me use the Digsite attack in Episode 1 to answer this, and break things down into three sections, as our work on that particular sequence spanned the entirety of the production schedule.

Preproduction

Previs formed the backbone for the worm attack sequence at the digsite in the first episode. The final photography stayed quite close to what we had blocked out during prep. Other sequences, like Mensah’s encounter with the female worm at the alien remnants crater, or the decapitation of one of Graycris’ secunits, were shot without previs since they were less complex in terms of choreography and interaction.

The digsite sequence involved multiple points of interaction between the worm and the cast, for which we utilized high-resolution digidoubles. While previs was ongoing, I began roughing out the worm creature in ZBrush to get an early sense of its form and physiology. Having a basic 3D model also helped me test its basic (facial) range of motion and confirm that the design could support the kind of action we were planning. As the model started taking shape, I moved into Photoshop to create a few paintovers exploring surface texture and finer skin details.

Working on both the previs and creature design in tandem turned out to be greatly beneficial to us. We were able to present showrunners Chris and Paul Weitz not only with a fully blocked-out sequence but also a set of fairly polished concept illustrations that gave a clear picture of the creature’s intended final look and feel. Knowing the model could perform as needed, and having their buy-in on the look early on, helped reduce uncertainty during later phases.

We also shared the 3D model with the special effects makeup department, who built a physical section of the worm’s head, which we used for lighting reference on set, alongside our usual sphere and chart plates. The model also proved helpful for the costume department with regard to Dr. Bharadwaj’s encounter with the worm. Since we knew exactly how she would be grabbed, they could create a ripped and punctured version of her outfit that would connect well with our animation later on.

For a few particularly complex shots, we also delivered techvis to help camera and SFX teams prep the rigs needed to shoot the plates.

Production

The majority of the dig site sequence was filmed on location at a quarry in Ontario over several days. Our biggest challenge proved to be the weather. Across just a few days, we went from bright blue skies with direct sun to overcast skies and rain. Even with the prep we had done, and confidence that the CG worm would hold up under different lighting conditions, lighting continuity for the sequence was going to be something we’d have to worry about later on.

Sean was able to shoot plates of our characters for nearly every shot, even in cases where we knew we might end up replacing them with digidoubles. Having real-world lighting and performance to reference throughout proved invaluable and helped ground the CG in reality. For quite a few shots we ended up bodytracking the photographed Murderbot with our digidouble, preserving the performance but gaining complete control over the lighting of the element, where needed.

Post Production

Our first task in post was bringing the creature animation from the previs into the live-action plates, most of which had been shot at high frame rates. This gave us the flexibility to retime the footage cleanly where needed. As we began blocking animation across the sequence, we were simultaneously refining the worm’s model, rig and lookdev. Having our creature and animation teams working in parallel also allowed our Animation Supervisor, Andrew Doucette, and his team to put the worm rig through its paces and relay any feedback to the rigging team directly.

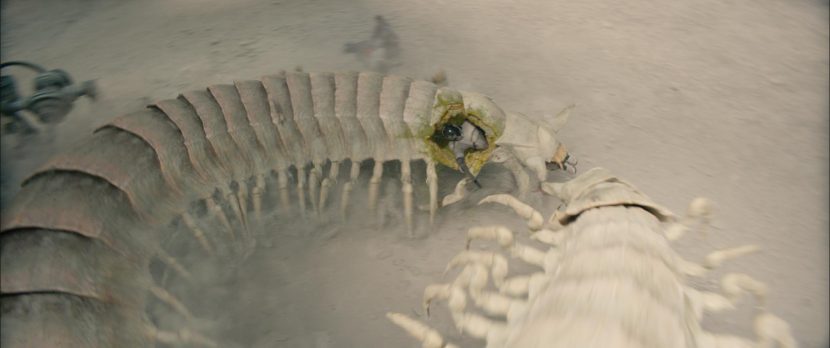

As we refined the animation, we evaluated which shots would benefit from swapping live-action elements with digidoubles. This gave us the flexibility to either push the action or improve integration. For the worm itself, we ended up creating three distinct models: our hero asset, a more detailed throat version, and a post-gunblast version used after Murderbot shoots through the worm’s body. On top of these, we maintained around 15 lookdev variations, reflecting increasing amounts of injuries and damage from Murderbot’s attacks.

Whenever we showed the worm taking a hit, we layered multiple FX simulations, ranging from ricocheting energy blasts on the harder carapace sections, to soft-tissue deformation, fluid sims, and a handful of severed limbs. All of this was layered on top of base-level skin and muscle simulations. Once creature animation and FX were final, we simulated environmental FX like dust clouds, fine sand particles, displaced pebbles, and ground punctures caused by the dozens of the worm’s pointy limbs.

Overseeing and tracking all of this was CG Supervisor Marc Austin, who worked closely with our lighting team to provide Compositing Supervisor Christopher Maslen and his team all the passes they needed to put the final shots together.

fxguide: How did your team approach the creature animation style for the alien species, especially were there any unexpected animation challenges, especially in how the creatures interacted with the environment or characters?

Jelmer Boskma: Our main challenge with the female worm creature was finding the right balance between erratic movement seen in real-world insects with similar design features and the need to convey real scale and weight. Early on, we knew that the animation couldn’t just be fast and twitchy. These creatures are massive, and their motion needed to reflect that, while still feeling otherworldly and aggressive.

The worm’s anatomy presented its own challenges. With dozens of limbs, two independently expressive heads, and a body that needed to feel physically plausible, a lot of the animation style was discovered through early motion tests. We experimented with how weight could shift between limbs, how quickly it could pivot or strike, and how the dual heads could operate both in sync and independently to create a sense of unpredictability.

One of the trickier aspects was integrating that movement believably into the environments, especially when interacting with characters. The sheer number of contact points with the terrain meant we had to allocate a substantial amount of time to clean up limb animation, to avoid the creature looking like it was floating or sliding. Likewise, when the worm grappled with a character, like Murderbot or Dr. Bharadwaj, we had to carefully choreograph the timing so the impact felt violent but physically credible.

fxguide: With multiple CG environments, Preservation AUX, Deltfall, Dead Worms Crater, the forest, what was your strategy for blending live-action plates with full CG enhancements, especially given the changing weather and lighting conditions? Any tricks or particular tools used in achieving visual continuity across the season?

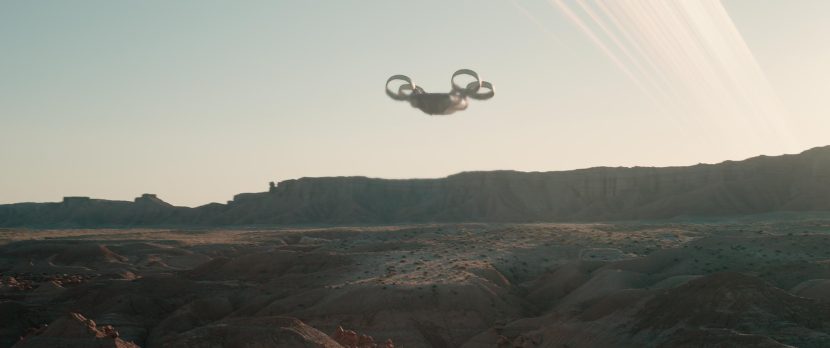

Jelmer Boskma: Each environment brought its own challenges and required a bespoke approach. Preservation AUX was the most extensive from a build standpoint. It appears throughout the season, often from different angles, across different days, and under varying lighting and weather conditions. Building it fully in CG gave us the flexibility to maintain visual continuity across all those scenes, and made the most sense in terms of scale and reuse.

The Dead Worm Crater, on the other hand, lent itself more naturally to 2.5D matte painting techniques, with the exception of some of the larger shots near the end of the sequence. For those, we built a sizeable section of the crater floor and surrounding hills to allow for believable integration of the dozens of worm carcasses.

For Deltfall, we enhanced the practical location with hundreds of alien trees and plants. Most of the vegetation was created as detailed 3D assets, though some trees were carefully rotoscoped and color graded from the plate photography. The Deltfall sequences, in particular, were a major task for our roto and comp teams, who had to isolate large portions of the live-action foliage to make room for our CG flora and other environmental elements.

Ultimately, this was well worth the effort as the blend of real and CG vegetation made that world feel far more grounded than if we had gone with a fully synthetic environment. Beyond the plant life, we added sulfur deposits, steam, hopper landing platforms, and a refinery to the lake. We also extended the practical Deltfall habitat, adding an upper level, two additional hubs, and connecting hallways in CG.

In terms of weather-related challenges, two sequences stood out. The first was Mensah’s climb up the crater wall in Episode 2, which was filmed in heavy rain. Since syncing simulated rain with photographed rainfall is virtually impossible, our prep team painstakingly painted out any visible raindrops from the plates. We then layered our own CG rain back over both the plate and the environment extensions.

The second major challenge was the worm attack in Episode 1, which I touched on earlier. We were hit with every kind of lighting condition over the course of that shoot: sunny, overcast, rainy, which posed a real problem for a sequence that plays out in under two minutes of continuous screen time. The solution was to normalize the lighting across shots by introducing sunlight into overcast footage, and cloud shadows into shots filmed under direct sunlight.

We were fortunate to have full LIDAR scans of the quarry location, which allowed us to project cloud shadows accurately onto terrain geometry that closely matched the plates. A set of partially cloudy matte paintings further helped unify the sky and gave the sequence the consistency it needed.

The biggest challenge was dealing with lighting on the actors. I really wanted to avoid artificially introducing or augmenting any lighting on them, as that can easily look fake or cheap. So we took a more grounded approach. If a shot was filmed under overcast conditions, we placed the actor in a cloud shadow. If it was shot in full sun, we kept the cloud shadow away from them. This subtle approach let us preserve the integrity of the photographed performance while still blending the scene visually.

As far as challenges caused by varying weather conditions, two sequences stand out. We were faced with heavy rain during the shoot of Mensah climbing the dead worm’s crater in episode 2, whilst we owed extensive augmentation for the background environment. As it would be virtually impossible to sync up any simulated CG rain FX with the photographed rain, we ended up having our prep team painstakingly paint out any visible raindrops from the plate. We then composited our CG rain passes back on top of both the extension and plate, and hopefully nobody would have noticed the difference.

The other significant challenge came with the worm attack in episode 1, which I alluded to earlier. We found ourselves with as varied a set of lighting conditions as imaginable, and for a sequence that plays in little under 2 minutes, we knew we had to do something about it.

The solution was to introduce sunlight into the shots that were photographed during the overcast days and to introduce cloud shadows into the shots that were shot in bright sunlight. We were fortunate enough to have an extensive set of LIDAR scans done of the location, which allowed us to render these shadows cast by our CG clouds onto geometry that closely resembled the terrain in the plates.

A set of partially cloudy matte paintings was used to further homogenise the scene visually and gave us the consistency we needed for the sequence to work. The most challenging part was working around the lighting on our actors, as I did not want to try and add or remove any light from them. It never looks right, and most of the time it can look cheap, even. So we opted for a method where, anytime they were shot during grey lighting conditions, we made sure they were standing in a cloud shadow, and when shot in direct sunlight, we moved our cloud shadows away from them.

fxguide: Can you break down the FX simulation work for elements like dust, blood, and weapon fire, particularly how you managed very fast-paced combat/head splats?

Jelmer Boskma: Our FX simulation work was all about layering, especially in the action-heavy sequences where dust, debris, blood, and weapon fire all had to interact in the same shot. For scenes involving the worm creature, one of the main challenges was managing the dust kickup and environmental impact caused by its dozens of limbs.

We approached this with a mix of soft volumetric simulations for finer, powdery dust and granular simulations for heavier particulates like clumps of sand. The creature also displaced small rocks and occasionally punched into softer terrain, so we built a system that combined contact-based emissions with enough art directability to allow for creative flexibility in comp when needed.

When it came to blood FX, we had some unusual targets to hit. The showrunners wanted the female worm’s blood to be a vivid emerald green, while Murderbot’s blood was imagined as a mix of blue, silvery, and red fluids. Simulation-wise, our approach didn’t deviate much from traditional blood FX techniques. We focused on getting clear, legible silhouettes, mixing fine mist, directional sprays, and thicker fluid elements to build impact and texture.

Especially in fast-paced moments, where a hit might only register for a frame or two, the key was to shape the sims so that they read graphically and immediately. In those cases, realistic fluid behavior is less important than making sure the audience feels the hit, through bold shapes, contrast, and timing.

fxguide: There’s a subtle beauty in the compositing work that often goes unmentioned. How did your compositing team maintain integration fidelity between the CG suits, creature FX, and naturalistic environments (and which renderer did you use)?

Jelmer Boskma: Thank you for mentioning this. Compositing often doesn’t get the recognition it deserves, and all the credit here goes to Compositing Supervisors Christopher Maslen, Varnica Mathur, and their teams.

One of the big advantages we had was working with real locations instead of soundstages, which gave us beautiful, natural lighting right out of the gate. But that also meant we had to be very deliberate with how we introduced our CG elements. Rather than overpowering the plate, the philosophy was always to work with what was captured, preserving the lighting, texture, and atmosphere wherever possible, and then layering in our CG in a way that felt organic and grounded.

We rendered using RenderMan, working out of Houdini, which gave us the flexibility to handle our CG environments, creature FX, and simulations in a unified workflow. Having clean AOVs and well-structured lighting passes allowed the comp team the ability to massage any specific aspect of the renders they were working with, whether it was making subtle color corrections to the lighting temperature or adjusting the atmospheric perspective in the deep background to work better with the plate.

fxguide: DNEG delivered 448 shots across 27 sequences. How did you manage consistency in Murderbot’s design and motion language across so many shots and directors? Did you have all the episodes turned over at once or did things develop as the series got shot ?

Jelmer Boskma: For the vast majority of shots across the season, Murderbot was photographed in-camera, with either Alexander or one of his stunt doubles in costume. Aside from a handful of helmet deployment shots and some enhancements to the helmet and arm blasters, most of what you see is practical. That gave us a strong, consistent foundation to work from in post.

From a scheduling perspective, things were turned over to us in roughly linear, episodic order, which helped with continuity and team focus. Episodes 1 and 7 were by far our heaviest in terms of shot count and complexity, so we requested that some of the larger creature shots be turned over early, even before the edits were fully locked, to give us a head start on planning and asset development.

Spearheading the effort of keeping everything on track was my producer, Vicky Gillett, who pulled off more than a few small miracles over the course of production, especially in managing a crew that was spread across multiple time zones. Her ability to keep things moving, while staying tightly aligned with both editorial and client-side reviews, was absolutely key to delivering the volume of work on time.

We were also lucky to have Chris and Paul Weitz heavily involved throughout the VFX approval process. Their direct creative feedback gave us a strong throughline in terms of tone, performance, and visual language. Sean Faden had an incredibly sharp sense of what they were after creatively, so our internal direction always felt aligned with theirs. That consistency—from showrunners through to on-set supervision—made the whole process as smooth and collaborative as anyone could hope for in a project of this scale.

fxguide: As a VFX supervisor, were there any particular sequences you personally loved, either because they were technically tricky or creatively satisfying? And what do you think audiences won’t realise was entirely CG?

Jelmer Boskma: With the scope of work across the series, there are quite a few shots scattered throughout the episodes that I feel were particularly successful, whether technically ambitious or creatively satisfying. Naturally, some of the larger centerpiece sequences stand out for the sheer complexity they demanded. But I also find myself drawn to some of our more subtle contributions, shots that may go unnoticed by the audience but were executed with just as much care.

Our CG extension work on the Hopper and the Preservation AUX habitat, for instance. Both assets were beautifully built and integrated rather seamlessly into the photography that they often pass as entirely practical. In many cases, we were completing partial set builds, adding upper levels, extending the overall structure, or finishing out the top and rear sections of the hopper, which had only been partially constructed on location.

These aren’t flashy shots, but they’re the kind of work that gives the world scale and credibility without drawing attention to itself. And for me, that’s part of what makes them so satisfying, they’re quietly successful. Audiences won’t realize they’re looking at CG elements, and that, for a VFX team, is often the highest compliment.

fxguide: Finally, Murderbot is both action-packed and character-driven. How did your team approach visual effects to support Murderbot’s emotional arc, especially as a character who’s constantly toggling between human empathy and synthetic efficiency?

Jelmer Boskma: That’s a great question. Murderbot is such a uniquely written character, and that’s only amplified by the way Alexander Skarsgård brings it to life. For the shots that required a digidouble, it was definitely a challenge to capture the same spirit through our animation. There’s a very specific balance to strike; confidence, aloofness, confusion, and just a touch of clumsiness, and it’s a narrow line to walk.

One sequence that stands out is when Murderbot jumps down from the crater’s edge to save Dr. Bharadwaj and Arada from the female worm. We couldn’t treat it like a superhero landing, it had to feel grounded in character. He stumbles, falls, picks himself up, and keeps going. There’s nothing graceful or perfect about that moment, but it’s exactly what makes it work. It’s very Murderbot.

I also remember one deceptively simple shot: our CG Murderbot walking toward the Preservation AUX habitat early in the season. It seems like a straightforward moment, but we ended up keyframe animating the entire walk because it needed such subtle tuning to match Alexander’s physicality. One version felt too confident, another too slouchy… then too jolly, too stiff, too mechanical. It took time, but we eventually found the right rhythm. It was remarkable how much of Murderbot’s personality came through in just that walk.

Outside of the character animation, our general approach to the visual effects was always about supporting the narrative and helping bring something new and otherworldly to the screen without pulling too much focus. That is, of course, unless we’re talking about a giant alien worm creature choking on our protagonist… In that case, we’re more than happy to take center stage.