Shane Black’s Play Dirty reinvigorates the hard-edged heist thriller with trademark wit, whip-crack dialogue, and kinetic set pieces, all wrapped around Mark Wahlberg’s sharp performance as Parker, a career thief with his own moral code. But for Australian viewers, there’s a strange, almost disorienting magic at play: the film was shot largely in Sydney, yet looks every inch the gritty streets of New York, as you can hear in this week’s fxpodcast. That illusion is thanks to DNEG’s VFX Supervisor Dan Bethell and his team, who transformed familiar Sydney backlots into the frozen streets of Manhattan.

Turning Sydney into New York

When Bethell joined the production in mid-2024, he arrived just as principal photography was wrapping in New South Wales. “Eric Brevig, the production VFX supervisor, was heading to Sydney with Shane,” he recalls. “I joined to help supervise second unit and the night shoots, which helped to see the setups and challenges firsthand.”

Those setups ranged from chilly winter exteriors to controlled night-time intersections, none of which, of course, had a flake of snow. “We collaborated closely with art and set design to sell the winter look,” says Bethell. “Sydney’s not New York, and it doesn’t snow here, so we had to work hard to achieve that authenticity.”

The production built partial sets, streets capped with 20-by-foot blue screens, which DNEG extended into fully digital New York environments.

The T-bone crash and the subway wreck

The sprawling New York intersection shootout sequence ends with Parker’s car being rammed, and it was entirely constructed in Sydney. “We built a partial intersection and extended the rest in CG,” says Bethell. “Everything from the surrounding buildings to traffic lights and snowbanks.”

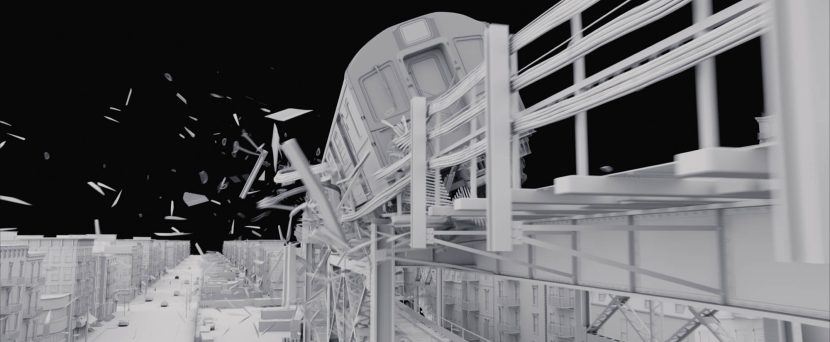

This led to the film’s show-stopping subway derailment, which demanded a meticulous blend of simulation and storytelling. The train crash was rendered through DNEG’s USD Solaris-RenderMan pipeline. Animation blocking started in Maya, but the destruction, forces, and interactions were handled in Houdini.

That VFX pipeline allowed the team to maintain cinematic realism while keeping the chaos readable. “It’s a viscerally immersive scene,” says Bethell. “But it’s also pivotal to the plot, so clarity was essential. We layered the sequence from gross motion to secondary and tertiary dynamics: the train, the destruction, the debris, even the snow kicks.”

Lighting authenticity was key. The team modelled huge sections of New York and positioned every light source correctly to light the scene accurately. Renderman did heavy lifting and compositing in Nuke then allowed the team to ” tweak the balance, but the realism began in render”, he adds.

Horses, heists, and a surprising challenge

At the other end of the tonal spectrum, Play Dirty opens with a daytime robbery that careens into a horse-racing track, a sequence that looked deceptively straightforward on paper. “We shot real horses and jockeys for most of it,” says Bethell. “Initially, I thought, ‘this will be the easier sequence. It turned out, not quite!”

One key challenge lay in the moment a horse vaults over a car, a mix of practical and digital artistry. On the day, the team got a horse to run over a padded, stationary car, with handlers and guide wires in shot. While not usable directly, it became perfect reference for the team. From there, DNEG built CG horses, complete with muscle and skin simulations, and digital jockeys with realistic secondary motion.

“The hardest thing,” Bethell notes, “was tone. You don’t want it to look horrific, but it can’t be absurd or cartoonish either.” The team iterated across versions, from the gruesome to the ridiculous, before landing on something thrilling but grounded. Wahlberg’s performance, shot separately against practical cues, became the anchor around which everything else revolved, as he was then composited into the action with the digital horses.

Lighting again became an invisible art. “Mark’s low in the frame, under these huge animals,” Bethell says. “We had to relight sections when he slides beneath or behind a horse. Bright sun, hard shadows, the comp team did an amazing job stitching it all together.”

The sunken Spanish galleon

DNEG started by tackling a fully digital underwater sequence: a centuries-old Spanish galleon wreck, with the object of Parker’s hunt in the film. “It’s the backstory, the MacGuffin,” Bethell says. “Only a few shots, but visually rich.”

The DNEG team drew on experience from their recent work on Fountain of Youth, which had required research into underwater light decay and spectral filtering. “Real deep-sea footage just looks wrong in a narrative context, too dark, too murky,” Bethell explains. “We wanted the found truth of underwater photography, but you still need to see what’s going on.”

Using Houdini and volumetric rendering, they created murky silt clouds, affectionately dubbed “fish food”, that gave depth and scale without the need for huge geometry builds.

Conclusion: invisible art

What’s striking about Play Dirty is how invisible DNEG’s work is. From Sydney’s disguised streets to the tactile grit of a New York intersection, to racecourses and underwater Galleons.. “We always ask: what serves the story?” Bethell says. “If the audience doesn’t notice we were there, we’ve done our job.”