Photo credit: Justin Lubin © 2025 Amazon Content Services LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Mercy judges a detective who is accused of murdering his wife, – in the near future, a detective (Chris Pratt) stands on trial accused of murdering his wife. He has 90 minutes to prove his innocence to the advanced A.I. Judge (Rebecca Ferguson) he once championed, before it determines his fate. The film was directed by Timur Bekmambetov, (Wanted, Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, and Ben-Hur ) with VFX by DNEG. We spoke to Chris Keller (CK) and Simon Maddison (SM), VFX Supervisors, who worked with DNEG Production VFX Supervisor, Axel Bonami about the film and their work.

fxguide: When did you first get involved with the film?

CK: I started on the show in August of 2024, when the Vancouver unit was brought online, mostly to take care of the shots featuring virtual screens.

fxguide: I believe the film was heavily shot using a virtual production volume (LED wall) at Stage 15 of the Amazon MGM Studios lot in Culver City, can you discuss how effective this was in allowing final pixels in shot? I imagine in addition to some digital extensions – there were shots where the lighting was useful but the ’screen’ context was redone in post?

CK: The courtroom was built in Unreal and wrapped around the set, so Chris Pratt was performing inside an environment that already had the right design language and, crucially, motivated interactive light coming from the same places it would in the final. Because we kept the look very consistent between what was on the wall during the shoot and what we delivered, we were able to stick to the practical photography for many medium and close-up shots, with little or no cleanup.

In wider shots, we’d often replace the volume with the final rendered courtroom and keep only Chris and part of the chair from the plate. Even then, the volume was still doing heavy lifting by providing lighting and reflections, which made integration easier.

The volume was extremely helpful for moving screens. Production ran temp screen animations on the wall, so any sweeps and pops were already happening during the performance. The exact content and layout evolved in post; we tried to build our CG screens around the timing that was baked into the photography. Only a small number of shots needed dedicated 2D relighting.

fxguide: On top of that, there were shots where clearly the screen became a full holograph around Chris’ character, could you discuss the challenges of those shots?

CK: A big part of the work upfront was defining that underlying logic: How do you get a believable 360 reconstruction from 2D source footage? How does it materialize in space? Where does Maddox (Rebecca Ferguson) go once the world around her becomes the display?

We grounded our logic in the way current AI systems segment images, isolate subjects, pull depth and layers where possible, and then inpainting what’s missing in the background. That gave us a framework to choreograph a loading / resolving animation that sells the idea that the AI is assembling the scene in real time.

The next challenge was lighting and integration. As I mentioned above, the photography provided good interactive lighting, but this had to be tweaked and augmented once final backgrounds were in place.

One not-so-obvious problem was the look of our virtual screens against a bright background. The UI look was very much developed against the dark courtroom. We had to tweak aspects such as transparency and diffusion to keep the screens legible without changing the overall look and feel.

Photo credit: Justin Lubin © 2025 Amazon Content Services LLC. All Rights Reserved.

fxguide: Because of the use of the LED screens, I’m guessing that the lighting on Chris across his face etc. was able to be capturing camera or did you have to do relighting in Nuke?

CK: Some relighting was necessary for key moments since the on-set animation didn’t always match the final timing, but we generally tried to design our VFX to work with the photography.

fxguide: Can you discuss how you approached the large scale destruction sequences, especially as the truck smashes through various roadblocks and police vehicles in the final act?

SM: Except for the truck driving through the homeless camp and hitting the food truck, all of the destruction was CG. Every police car crash, ejecting driver and civilian car crash in that sequence was generated digitally. There was a plate shot of the truck crashing through a fence, but it was ultimately replaced with a CG version for framing purposes. We also had some footage of the truck crashing through police cars, but once again, we decided to replace it.

Having a collection of very robust vehicles set up for destruction was key, having built and tested them extensively so that by the time we were putting them in shots, they behaved as expected. The reference shot on set was also remarkably helpful. Even if it wasn’t ultimately used, it showed us EXACTLY how the action should play out.

fxguide: How did you arrive at the final look for the municipal cloud? Was this conceptualised close and tight before the team started based on the art department? Or was there more experimentation and investigation to come up with the final look?

CK: Production ran temp graphics on the volume, which consisted of a few dozen screens with temp footage, more or less randomly instanced. This gave us useful interactive light, but it needed a proper redesign.

The brief was that the cloud should overwhelm Chris and the audience, but it couldn’t feel random. We looked into real-world database visualizations and then defined a simple internal logic. The idea is that data is organized in hierarchical clusters: the first layer is always location footage (CCTV, phone, bodycam). Anything of interest inside that footage spawns a second layer of smaller screens with deeper reports, and some of those spawn a third layer (passports, bills, fines, that kind of thing). The result is a fractal structure that can fill the room while still feeling organized.

DNEG Production VFX Supervisor, Axel Bonami and the editorial team assembled a huge library of footage and images, and we had a separate ingest unit on the show whose only purpose was to import the insane amount of footage. It was immediately clear that the scale of the cloud required a full 3D solution (while most of our other screens were achieved with an advanced Nuke setup). We loaded the data into Houdini and instanced it procedurally. We followed that with an art direction pass, where we would remove duplicates and create hand-crafted hero clusters for the foreground. Finally, we matched the established UI design by building RenderMan shaders that carried over the Nuke lookdev: bevels, glassy diffusion, and subtle reflections, including self-reflections.

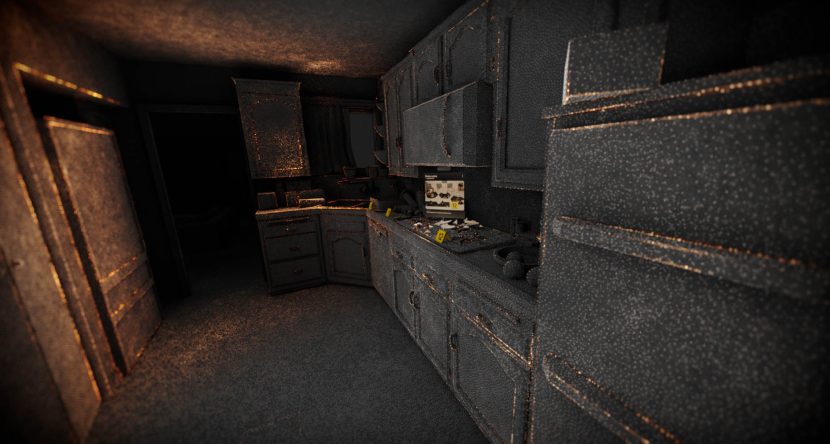

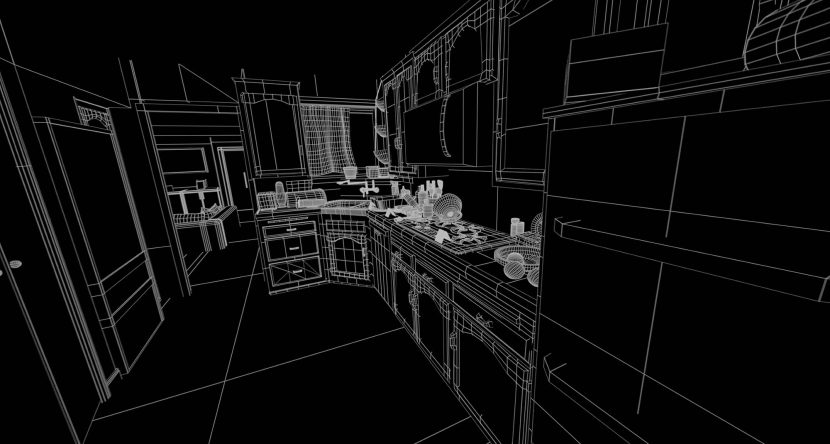

fxguide: I was fascinated by the forensic crime reconstructions. I’m assuming that you used either LIDAR or Gaussian splats? Could you discuss the methodology behind these sequences especially in the kitchen and the house?

CK: That’s a great observation. Yes, we did look into both LIDAR and splats. We spent a lot of time studying real-world forensic workflows, because we wanted those reconstructions to feel grounded (with a futuristic polish and real-time AI technology thrown in the mix).

We did experiment with Gaussian splats early on, but we ultimately landed on a cleaner point cloud methodology. Splats are not terribly pipeline-friendly and can be difficult to art direct, and the aesthetic we were after was more sleek and with a focus on readability. The same applies to true LIDAR. Real scans tend to be noisy and uneven, and if we had used them literally they would have overwhelmed the viewer. So what you see in the film isn’t raw LIDAR data. It’s an artistic recreation that follows the logic of forensic scans and recreations.

Our approach was to start with clean proxy geometry of the crime scene, and then generate controllable point cloud representations at different densities (light, medium, and dense) that we could mix depending on the story beat and what part of the room we wanted to emphasize. To keep the image legible, we also rendered supporting passes like occlusion, lighting, and edges. Occlusion was particularly important. Foreground objects needed to properly block the points behind them, otherwise you end up reading multiple layers at once, and it quickly becomes visually confusing.

From there, a lot of the final feel came from compositing. We used depth and position data to drive depth of field, shape the focus, and create scanning behaviours like radial pulses.

Photo credit: Justin Lubin © 2025 Amazon Content Services LLC. All Rights Reserved.

fxguide: One of the interesting vehicles of the future was the police drone. Can you discuss how that was created and integrated, particularly given the significant downwash experienced by those around it during take-off? Also, when the policewoman is thrown off, I’m guessing you used extensive digi-doubles? Or did you need to rely more heavily on stunt performers as well, especially for the crowds that scatter as the truck approaches?

SM: The down draft from the drone, when it was on set with a gimbal or crane arm, was practical and worked with great effect. Sometimes we augmented it in post with 2D elements. Any wide shots, for example, when it sweeps past the truck and begins travelling backwards looking into the cabin, because this shot was entirely CG, the wind was generated in comp.

The Quadcopter pilot was scanned, giving us a highly accurate digital double of her. This worked for a lot of mid-shots, and most importantly, for when she was thrown from the vehicle.

Other digital doubles in the film included the pedestrians, the homeless, and police and SWAT team members. The crowd parting in front of the truck was 100% CG, so we had a crowd system setup for that. For more specific shots, such as SWAT teams landing on top of the truck or being thrown from crashing police cars, we employed assets with a higher level of detail.

Extensive Motion Capture was performed for the crowds, as well as some of the more specific stunt action. A lot of the previs for the film was done by Proxi in Australia, which provided excellent capture reference. We also did some crowd work at the DNEG Mo-Cap studio to augment that work.

fxguide: thanks so much guys!

© 2025 Amazon Content Services LLC. All Rights Reserved.