In this interview we talk to Digital Domain visual effects supervisor Matthew Butler about his team’s 350 shots for Transformers: Dark of the Moon. Responsible for the characters Laserbeak, Brains, Wheels and the Decepticon protoforms hiding out on the moon, views of the space bridge, as well as the elaborate Bird Men skydiving sequence, Digital Domain this time handled all of the shots in stereo for the film – director Michael Bay’s third Transformers outing. Additionally, Digital Domain’s sister company, In-Three, handled some of the 3D conversion.

fxg: Can I start with Laserbeak, who I think came across as such a great combination between being a real messy character but also very calculating. How did you approach him?

Butler: Laserbeak is this evil, sinister, assassin killer. He’s the cleaner. He’s sent to clean up and whack out all the humans that have been used by the Decepticons over the years. We would start with an initial direction from Michael, and a little bit of temp dialogue. We would start animating and then Michael would interview voice-over actors and then we would re-animate based on the new behavior.

There’s a scene where Laserbeak is interacting with the character Jerry Wang, played by Ken Jeong, before he is killed. Michael Bay is very much into hands-on behavior on set. We had this little blue sock with a tool in it that we puppeteered to move Ken Jeong’s glasses around his head and ruffle his hair. And then we put in the CG character around him, as if Laserbeak was the one interacting with Jerry’s face. We actually resurrected some slimy saliva that we developed for Alice in Revenge of the Fallen for Laserbeak in that scene.

So Laserbeak was very much a character defined by the on-set interaction. And we did the same thing with the other characters. When Wheels jumps up on Bonecrusher, the dog, we got some little tongs and moved his ears around. Michael’s a big fan of having something in the plate that’s photographically real, and then working around it, and setting the tone.

fxg: There’s a fun scene of Laserbeak when he’s pursuing Sam at the office building and has to fly in such a confined space. What did you have to do in terms of making that scene work?

Butler: We went round and round with that one. At first we did an animation study and made him a chaotic bird that flapped its wings. And a lot of the time, Michael didn’t like that – I think it was just too friendly a behavior. So then we investigated this notion of Laserbeak having a delta-wing pose, because he has these ducted fans for thrust, so he didn’t have to fly like a bird that we’re used to. But we had to decide whether he was flapping his wings or thrusting his engines, and we ended up with some sort of hybrid.

In one scene he ends up in the server room and he “Terry Tates” – wham! – into the side of a filing cabinet with racks of computer gear and he stumbles and stammers to the ground. In that case, Michael said he should rag-doll a little bit like a trapped bird that gets caught in your house and starts to freak out. Michael was the one who suggested making it messy.

fxg: What tools were you using to model Laserbeak and the other characters such as Wheels and Brains?

Butler: In general, everything was modeled in Maya. Now and again we put extra detail in by using programs like Mudbox. All the lookdev was also done through Maya and rendered almost entirely through RenderMan. There were times when we would do a pass here and there through V-Ray or Mantra.

Michael is a huge fan of complex, highly-reflective lighting. Every day on set there is not one thing that he doesn’t light in that manner. He will always have the DP or a gaffer with reflector boards made of mylar or broken mirrors with colored 1Ks pumped into them. So the lighting is always incredibly complex. Luckily nowadays our vocation is not considered ‘post’ – we are there on set to acquire all that data because we’ve got to match that feel. And we would do all that data acquisition, including animated HDRs and projections and video reference.

fxg: Can you talk about Brains and Wheels – what’s behind the smoke emanating from Brains’ hair?

Butler: [laughs] The production designer, Nigel Phelps, would put together some concept art that Michael approves. We had some pretty good artwork for Brains, who was designed as a sidekick with two wheels. Then you look at the dialogue and he would say things like, ‘I got something – hot, hot, hot! I’m smokin’ here!’ He was this over-clocked, hyperactive, CPU-powered robot. We talked about him arcing and steaming and that’s what we added in. Michael ended up loving Brains and the smoking hair, because he just thought it was funny. There was actually a shot earlier in the movie where Wheels put him in the fridge, and we did a character study of him coming out with a bag of frozen peas on his head, but it got cut before it was even filmed.

fxg: DD also worked on the wingsuit Bird Men sequence – what were the broad strokes of that?

Butler: I was in Chicago to supervise the plate photography on that sequence. Julian Boulle wore a stereo camera rig on his helmet which had two SI-2K cameras mounted to it. JT Holmes headed up the ‘squirrel’ team which had three others, so there were always five jumping. We had long conversations with that group early on. They did a phenomenal job but I think we also did a great job supporting their mad antics. Their stunts were amazing, but we added CG vehicles, digital environments and also a bunch of CG birdmen for some shots.

fxg: How far was the sequence planned out or previs’d?

Butler: There was a lot of planning generally. There was a lot of scouting. We ‘flew the roofs’ out there and found out where and when to drop people from a helicopter or a building. One interesting side note is that the FAA requires anybody jumping out of an aircraft to be wearing a back-up chute. But these guys are basejumpers and have never flown with two separate chutes, because if you’re pulling at 500 feet, there isn’t time for a second chute. It’s actually dangerous for them to wear two because it alters the airflow and weight. But the FAA put their foot down and wouldn’t let them jump without it. So they did a couple of test jumps. Then the irony was – when they jumped off the buildings they didn’t have to have a second chute, because there was no federal control. So they could ditch having two chutes and just jump with one!

We always had one helmet camera running, then we always had three ground cameras and one Spacecam on the helicopter. We basically rolled everything we had, because it was a very short jump – you get maybe six seconds of useful air time. I scoped it out with the jump DP, Rob Bruce. We picked rooftops to cover from. Then there were also a number of fully synthetic shots, and I would go and shoot plates for those to use as reference.

fxg: What kind of shots did you have to deal with for that Bird Men sequence?

Butler: We had everything – we had shots that were blurred with panning cameras. Some of the hardest were the SI-2K stereo rig helmet shots. That camera has a rolling shutter where the sensor on the array scans from left to right, top down. If you’ve got a fast-moving camera, by the time the sensor’s reached the end of its sensing, the content may have moved position. And you get this real warbling feeling. So if you pan a camera with a slow uptake fast, vertical lines end up looking a bit like bananas or soggy noodles.

It’s tolerated by the eye, but the nightmare is, how do you simulate that in a synthetic world? What does it mean to track a camera and create a synthetic one that matches a real life camera but wouldn’t have that artifact. If you put a CG object in a scene that does not have that aberration, it won’t fit with the rest of the scene. We also shot on the Sony F35 which is a spherical camera and doesn’t have any rolling shutter issues, nor does a film camera which has a very discrete shutter. We also had to deal with all these issues in stereo as well – stereo from the F35, the helmet rig and provide 2K post-dimensionalized plates, as well as fully synthetic stereo.

fxg: What were the assets you had to build for that sequence, like the Ospreys they jump out of?

Butler: Well, we had those but I think the hardest things were actually the fire and smoke. Digital Domain is historically very good at naturalistic effects. For one shot when they jump out of the back of the Osprey, the whole thing was shot overcranked at 120 frames per second. So you really get to study it – and there’s not a lot of camera motion. You have this Osprey outside that falls past camera and we hang on it for a long time, and it is hyper-hyper real. We spent a lot of time developing that. There’s also a lot of city destruction and moving cameras – so we needed to see a lot of parallax. We ended up doing a lot of smoke plumes in 3D rather than as photographic cards. Michael wanted to make sure also we had the correct light direction.

fxg: What tools were you using for your fire and smoke?

Butler: We lean heavily on Storm, our proprietary volumetric renderer. That and Houdini are the two main workhorses for volumetric, natural phenomena or gaseous effects. Then we use FSIM our proprietary fluid sim for water and splashes. But it’s always the people, not software, who create these beautiful images. We had a team of about 27 people just for the effects.

fxg: What about the digi-double work for the sequence – did you have an opportunity to scan the jumpers at all?

Butler: The jumpers never got close enough to camera to need digi-double work. Meaning we had to do photorealistic birdmen, but we didn’t have to match particular actors. We had a ton of reference from the birdmen guys, which we studied laboriously and matched in terms of animation. We also sim’d the cloth – it’s a tactile thing and we had to see how it plays. It’s not necessarily how you think it would be. We had our modeler and lighter over there and put a lot of attention on that. We also added detail with the lighting, translucency, kicks, the decal and the animation for how the guys would get hit mid-air.

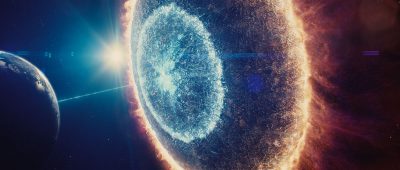

fxg: Can you talk about the shot of protoforms coming out of the moon? Because it was a fully synthetic shot, how did you approach that to give it a real-world feel?

Butler: My rule is that whenever you’re looking at a fully-CG shot, you need something that grounds it in reality. So a lot of attention was put into making the animation as realistic as possible, so you’d say, ‘Oh that’s bipedal behavior – I’ve seen that before, I can grab onto that.’ We’ve also seen natural phenomena of particles moving before. Maybe we haven’t seen it in zero gravity, and we haven’t seen it that commonly in a vacuum, but we’ve seen something like it.

We could have played the moon dust exactly as it should have behaved in those conditions, but it would have looked a little alien. So we let some things creep in that we’re used to on Earth, again to give the audience a visual point of reference that feels real. And we’ve all seen photographs of the moon. We put a lot of energy into studying that. Mårten Larsson, one of our CG supervisors, studied it until the cows came home and he wrote an incredibly realistic shader. And then we added as many optical aberrations as we could like lens flares to give it a photographic feel.

fxg: You’ve mentioned the stereo work, but what were some of the particular stereo challenges on this show?

Butler: Well, for starters we were shooting with so many different cameras and each one has its own idiosyncrasy – F35s, anamorphic film mono, spherical film mono from the Spacecam work, and also stereo SI-2K. We even shot a bunch of video for things like the Decepticon vision because Michael wanted it to be very real and hand-held.. We have to study each format and match the color gamma and everything. So it’s not just about getting it in the can and then it’s done for us – there’s a lot of behind the scenes work.

The increased workload was a challenge as well. It’s not always as easy as rendering out another eye. There are a lot of tricks we use in a monoscopic world that we can’t use anymore, such as “paint fixes.” You can’t do a lot of paint in stereo because the ‘cheat’ gets exposed in the other eye. For anything shot in stereo, we also have to match our CG assests to the camera and define the interocular separation and the convergence. Someone has to work out when that comes into play and whether it will work editorially with the other surrounding shots. So stereo necessitates a lot of extra work right from the word “go.”

The increased workload was a challenge as well. It’s not always as easy as rendering out another eye. There are a lot of tricks we use in a monoscopic world that we can’t use anymore, such as “paint fixes.” You can’t do a lot of paint in stereo because the ‘cheat’ gets exposed in the other eye. For anything shot in stereo, we also have to match our CG assests to the camera and define the interocular separation and the convergence. Someone has to work out when that comes into play and whether it will work editorially with the other surrounding shots. So stereo necessitates a lot of extra work right from the word “go.”

Finally, we have to deliver a ton of assets to the conversion houses, one of which was our sister company In-Three. We give them all kinds of elements, like z-depth renders and Nuke scripts that help integrate stereo conversion into the visual effects process as a whole. This too involves a lot of work, but the combination of proper planning along with a smooth workflow ends up producing better stereo 3D in the end.

All images copyright © 2011 Paramount Pictures. Courtesy of Digital Domain. All rights reserved.