At fxguide we’ve covered some incredible invisible visual effects work in the past, and now we present two examples that again evidence the key role VFX studios play in helping to tell director’s stories; Creed, Point Break and Southpaw. Find out how BigHugFX delivered seamless environments for a boxing sequence in Creed, how Image Engine produced invisible visual effects for several of Point Break’s action scenes and how Zero VFX also helped make convincing boxing scenes for Southpaw.

Creed

Director Ryan Coogler’s Creed from MGM and Warner Bros enthralled audiences late last year with its continuation of the Rocky Balboa franchise. Part of the appeal of the film, which sees Sylvester Stallone reprise his famous character as a trainer to young boxer Adonis ‘Donnie’ Johnson (who turns out to be the son of former heavyweight champion – and former Balboa rival – Apollo Creed) were the impressive boxing scenes. Meticulously constructed with raw performances and immersive camera work, the ring bouts were also made possible with the help of visual effects supervisor John Nugent and his team of VFX studios. Among them was Munich-based BigHugFX which worked on Creed’s final fight – a rousing sequence depicted in Goodison Park, Liverpool.

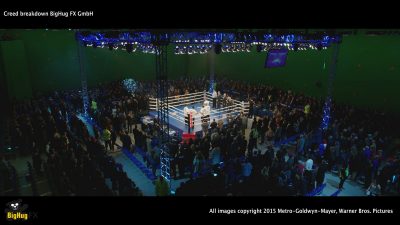

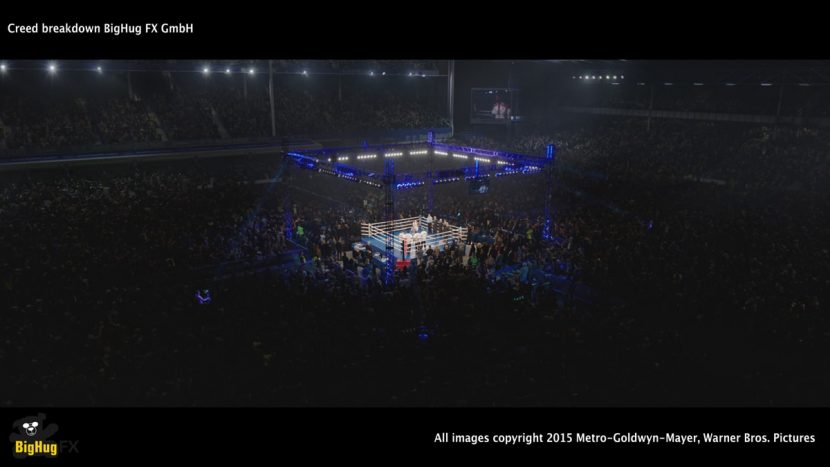

“Our main task was to create a realistic crowd and stadium background,” explains BigHugFX CEO and visual effects supervisor Benedikt Laubenthal. “Some of the hero shots needed a full CG crowd and full CG stadium, others could be solved with a 2.5D solution – the production company had been shooting a full 360 degree panorama inside the actual stadium in Liverpool when it was packed with fans waiting for a soccer game to start.”

The final sequence required 350 visual effects shots, of which BigHugFX crafted 141 with a team of 18 artists over five months. The rest of the shots for the sequence were completed by Sandbox F/X and East Side Effects. Live action was filmed in a greenscreen studio, with the first couple of rows from the boxing ring filled with crowd extras. “John was on set to grab all measurements and take care of a well lit greenscreen and good tracking possibilities,” outlines Laubenthal. “Nevertheless, the DOP’s as well as the director’s vision was to replicate an actual boxing match as close as possible, which meant that there was on-set fog and roving spot lights. John made sure that this wouldn’t hamper the keying process.”

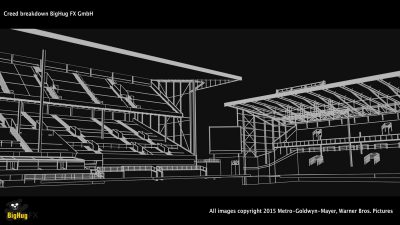

BigHugFX was then tasked with extending the principal photography with a CG version of the Goodison Park stadium, and with crowds. “We had a lidar scan of the stadium to use as a base and it was good enough to use as a reference for all of the necessary detail,” says Laubenthal. “A low-res version was also made for matchmovers and compositors to always be sure about which direction the camera was pointing in each shot.”

In NUKE, BigHugFX artists established a 360 degree panorama setup using footage taken from a soccer match at the Goodison stadium. “It was shot on eight RED cameras bolted to a rig and provided enough overlap between each of them to stitch everything together in NUKE,” states Laubenthal. “Lens flares needed to be painted out and a few empty seats needed to be filled. Everything was then pre-rendered as a cube map with 10K tiles and forged into a 3D gizmo that could easily be updated and shared with our co-vendors.”

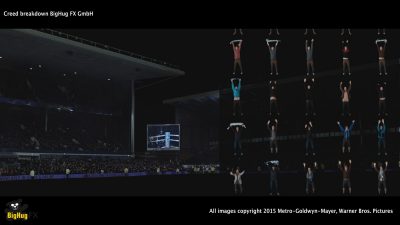

A two-step approach was formulated for the crowd. First, live action extras were filmed doing various performances and then placed onto cards in NUKE. These were then mixed with digital crowd elements generated in Houdini, allowing the visual effects teams – which shared stadium shots – to “pick the right solution on a per-shot basis and re-use as much as possible to get shots done quickly for test screenings,” says Laubenthal.

In particular, the Houdini effects crowd made use of 40 different animation cycles and 50 different character models, with switchable clothing – the result was a diverse mix of spectators who would be cheering, shouting and clapping at different moments. “I think the key,” suggests Laubenthal, “was to be flexible enough for change requests of any kind since caching and rendering a CG crowd takes time. So we tried to incorporate actual people.”

BigHugFX also found a way to make the construction of crowd scenes even more efficient. “We had the whole staff of BigHugFX dressed up as boxing fans and filmed on our own greenscreen stage whenever the behavior of only specific characters needed to be replaced,” describes Laubenthal. “This allowed us to move that work to the comp department and avoid time-consuming re-rendering of CGI.”

All images copyright 2015 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures, Warner Bros. Pictures.

Point Break

Image Engine is known for working both on large scale visual effects films and producing stunning ‘invisible fx’ work also. Recently they were one of several studios which contributed to Ericson Core’s Point Break re-make. Amongst some stunning stunt and special effects work, the studio’s visual effects, which were overseen by overall supervisor John Nelson and Image Engine’s Andrew Chapman and Dave Morley, had to match the very practical aesthetic established in the film.

In an early daring sequence, the criminals unload millions of dollars from a palette of bills over Mexico – while skydiving. Shot with real skydivers over a desert environment, production also launched the skeleton of a weighted down cash palette from a plane. “It had some tracking markers on it but it formed just the sillouhette of the palette,” explains Morley. “At least the skydivers when they jumped had something real to look at – they had to actually find their way to this practical palette and grab onto it. It gave us real lighting reference and great reference to work with.

Image Engine then added digital cash as bundles onto the palette and, upon their release, a waft of flapping notes. “We matchmoved the palette itself and did a lot of rotoscoping,” says Morley. “The cash was a bunch of Houdini work. We had a lot of caches of flapping notes and a dynamic rig that allowed it all to jiggle around. Then there was the environment below which we replaced to be more like a jungle and we also added digital clouds done in Houdini.”

Towards the end of the film, the criminals look to subvert the operation of a gold mine by detonating explosives that take out a convoy of trucks carrying gold ore. Afterwards, they escape and motorcross bikes.

“The first part was the detonation of the side of the mountain which causes the avalanche,” recounts Morley. “There were no practical elements shot, it was all digital explosions, matte paintings and environments. We had LIDAR scans of the whole environment, we had digital trucks and everything combined to build the world and understanding where the explosion was happening versus the trucks.”

Image Engine produced heavy rigid body sims for the explosion in Houdini, with rendering in Maya through 3Delight. “When you look at the reference of what an avalanche or landslide looks like it’s more often than not a complete obliteration into dust and you don’t read the fine detail of rocks and everything coming down,” notes Morley. “The filmmakers, however, wanted to be able to see everything that’s going on. It was a bit of a back and forth how much we can cover it with dust versus how much we want to actually see. It evolved from a very dry landslide to one being a bit more wet, so it kind of felt like a mix of mud and dirt.”

“Image Engine have some great tools for how we pass data from Houdini into Maya for rendering,” adds Morley. “We were essentially just passing points – millions – and were all being tagged with IDs which were dynamically picking up rock assets which we being procedurally textured at render time. I don’t think that could have been done any other way. We also used our own lighting and rendering solution called Caribou.

Image Engine also produced effects for a sequence atop an Italian mountain where the lead criminal attempts a bank heist. This scene was filmed at a real location that contained a gondola station, but would be fleshed out with an entire village (street level scenes were filmed elsewhere). “For the outskirts of the village,” states Morley, “they used this exterior location and we had to place a digital village into it. There’s a couple of big stunts where he jumps onto the top of a gondola which was all done in camera with a lot of wire work. There’s also fight sequence they’re on a gondola which was shot on stage – we had to do a digital environment that surrounded it and linked it to the location.”

Finally, Image Engine combined with Scanline VFX for a selection of free climbing shots at Angel Falls, Venezuela. “They shot a lot at the location but had free climbers doing the climbing,” says Morley. “So what we did was some digital face replacement based on Light Stage face scans, while Scanline did a lot of sims to fill the falls up with more water.

All images copyright 2015 Warner Bros. Pictures.

Southpaw

https://vimeo.com/152353371

In Southpaw, starring Jake Gyllenhaal as Billy ‘The Great’ Hope, director Antoine Fuqua once again turned to the specialists at Zero VFX to help bring some key scenes to life. Many of the boxing scenes made use of extended digital environments and some subtle sleight of hand compositing work to help land devastating boxing blows.

The fights were filmed in a small arena against black, then turned into Madison Square Garden and Caesar’s Palace locations with CG stadium sections, crowds and lighting. “That’s prevalent for many, many minutes of the film,” said Zero visual effects producer Brian Drewes in a release. “We didn’t attempt to escape from any of that – we built it all by hand.”

Fuqua shot the boxing scenes round-by-round, a somewhat unusual approach to tough sequences like this. “The production shot three rounds at a time, using 15 different cameras,” remarks Sean Devereaux from Zero, Southpaw’s VFX Supervisor. “The actors would do a round, go and sit in their corners, do the lines they had to do, then get back up and keep boxing, all while the cameras continued to roll. We weren’t working with specifically designed shots, where we stop the action to cut to inserts or cutaways for cool punches. It was all in real-time.”

Then, Zero assisted by adding in the CG crowds and stadium as well as making the actual fighting as intense as it could be by helping to connect punches. This involved repositioning actors, head adjustments and generally adjustment the movement following a blow.

“There’s not a single near miss where the sound effects do the work,” says Devereaux. “Every punch thrown that is supposed to connect with the other fighter makes contact with their face, warps it, and spit and blood are ejected. That’s every single punch – there’s not one that misses unintentionally over the film’s 35 minutes of boxing.”

All images copyright © 2015 Weinstein Company.