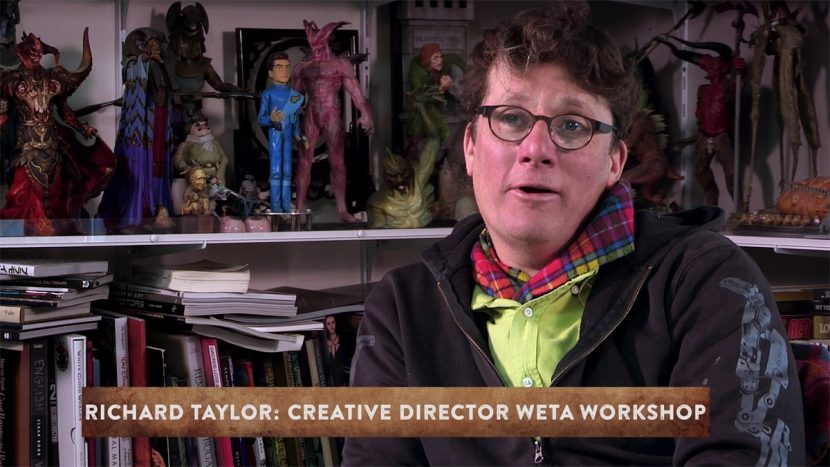

The fourth installment in George Miller’s apocalyptic Mad Max saga is now out on DVD. We spoke exclusively to the team at Weta Workshop headed by Creative Director and five time Oscar winner Sir Richard Taylor KNZM about their contribution to the development of Fury Road, and how educational the Weta team found George Miller.

Above: Sir Richard Taylor and members of the Weta Workshop team discuss their conceptual work and makeup, costumes and props for Mad Max: Fury Road.

Mad rides – finally

Richard Taylor is first to point to the team effort on Fury Road, helped enormously by the team not only having outstanding designers but some real ‘petrol heads’ among them – for which working on the film was a near perfect pairing. He could not speak more highly of how the Weta Workshop’s efforts were respected and reviewed by George Miller on this project, in fact, he found it highly “educational and a warm embracing of the creative process, as George stopped and shared his philosophical views on how to make the movie and how to build the shots, and how to creatively inspire the story.”

“He asks for your opinion,” adds Taylor, “and he involves everyone on the team in every stage of it, from our youngest designer to our most seasoned.” Of course, given the history of the Weta Workshop, Taylor has worked with some of the most successful and collaborative directors of the modern age, and he takes nothing away from any of those he has worked with before. But he did comment that “I found – as a company operator myself – to have that endorsement given back to the team working on the Workshop floor, where every effort they made was acknowledged with a thoughtful dissertation on their work, was really enriching.”

Taylor laughingly commented that this education even extended to his own vocabulary around the Workshop. He recalls since Mad Max several words are now in common use at the studio for the first time. “I’ll give you two examples – antecedent (as in the preceding event, condition), and jingoism (extreme patriotism, especially in the form of aggressive or warlike behavior or support). Jingoism is a very important word when you are looking at cultural influences in a film setting such as this.”

When done, Weta Workshop would deliver to George Miller 673 designs of vehicles, characters, makeup, costumes and props. They did actual R&D and prototypes on everything from the Gastown people to the Pretorian, and they even delivered 30 full body dummies for use in stunts and explosions. In all the project would span several years, six months of which the Workshop worked intensely on the world of Max Rockatansky.

Culture, practicality and being a bogan

Fury Road had a long and somewhat painful birth; many times over a period of ten years the film was on again off again. Around the time that Miller was completing Happy Feet 2 in 2009, Weta Workshop was contacted to embrace the work done in concept art to date and help move the film fully into hard core pre-production. Apart from the vast track record of skilled artistry, Weta Workshop provided several other logical reasons for joining the team. Firstly they have a long history of helping to develop culture and a unified sense of ‘being from a place’. When you see Weta Workshop’s designs you believe there is an entire valid history as to why things are the way they are – the material used, the iconography and the design aesthetic all seem of a place and of a particular people. This comes from years of experience, experience very few groups anywhere in the world can match.

Secondly, Weta Workshop’s team has always been focused on the tangible and the physical. At the point the team joined Mad Max, there was a need to move from just concept art in a design exploration sense to concept art that could be built, encompassing the needs of production as much as the practical restrictions of engineering and construction. Weta Workshop build things, and real things – especially real cars and props – and that was exactly how George Miller wanted to make this newest film.

Finally, Weta Workshop, by their own admission, were die hard muscle car Mad Max ‘bogans’.

A bogan, if you explore the world of online slang, is defined as:

bogan ˈbəʊɡ(ə)n/ . noun of AUSTRALIAN or NZ informal derogatory. An uncouth or unsophisticated person, regarded as being of low social status. For example: “some bogans yelled at us from their cars”.

An insult to some, maybe, but for a few very self deprecating and insanely talented artists in Wellington it was a badge of honor to be worn and exploited. If visually the film was to be made with real props and real cars, then the visual authenticity needed to extend to a faithful amplification of the sub-culture of muscle cars and ‘rev-head / motor head’ culture. As Taylor explains, “The Australian car culture first and foremost, then the fans of the material, and then finally the car fans of the world would have smelt a rat – so fast!”.

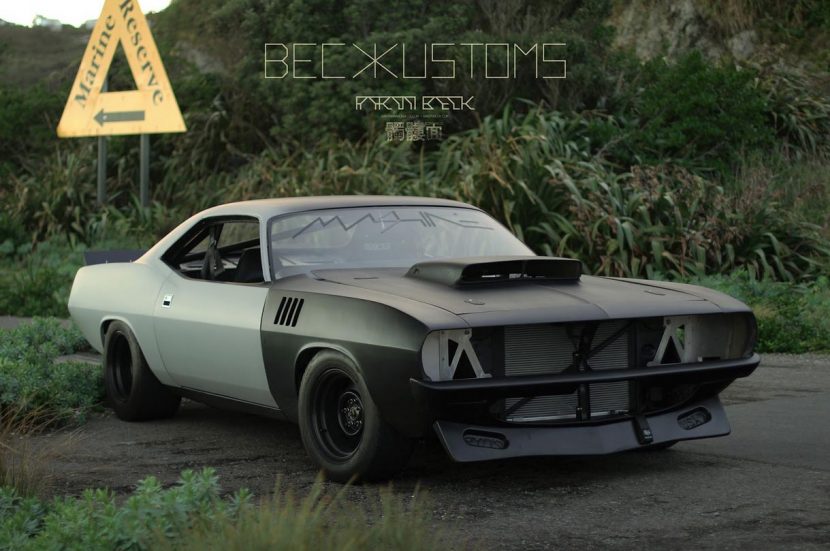

“In a sense you have to be a bogan at heart,” says Taylor. “If you are to design fast cars, hard guns and tough women in this design world, the spirit of design that has to be embedded in these sort of films needs people – needs designers – that are in touch with the material.” Indeed, Taylor offers the example of Weta Workshop’s Aaron Beck who is building a muscle car as a piece of fine art, which you can see at Beck Kustoms.

One of the great strengths of Weta Workshop’s concept design team is that it is so influenced by a wealth of experience in actually then turning designs into real things. Thus it was that an initial idea that George Miller had about having Warboys on poles as a way to swing them on to attacking vehicles was moved via Weta Workshop, from bending poles to counterbalanced pivoted swinging poles that one sees in the movie.

A swinging pole is both unstable and hard to work with a moving vehicle. “George had been walking somewhere in Sydney and seen people on poles,” recounts Leri Greer, senior art director at Weta Workshop. “The idea came to him that that might be a really good idea to deliver people over to vehicles.”

In Sydney, tests were done with stunt people at a disused airfield but they were not working due to the physics and inertia inherited from the base vehicle. One of the Weta designers Stu Thomas solved this, he suggested that “instead of a pole fixed the vehicle – add a pivot point with a counterweight and it will work independent of the physics of the vehicle,” says Greer. The Workshop debated and refined the idea and passed it to the Sydney team who then built and tested it, and this design is what was used by the stunt crew in Namibia during principal photography.

Visual style

Each group in the film have their own culture, back story and thus visual style, but this extends to much more than just making the groups look different or ‘cool’. The essence of good design is to build from the back story to inform the design decisions. A culture builds up and has it own aesthetics, but not arbitrarily – there will be reasons why they use a certain type of metal, why they adapted – it may be climatic, political or geographical, but a consistent piece of design from Weta Workshop has this thread of backstory informing all of an on-screen group’s costumes, weapons or vehicles. Weta Workshop does not seek to ‘get through’ the backstory so they can get a winning design, they embrace the backstory and the cultural dynamics that got the characters to the place they are at when the film starts.

Greer says the process was interesting given the mixture of mythology from the first few films and what George was trying to say. “There was conversation about what had gone before and then there was this new thing we were building up”, he explains, pointing out that in the second and third films “you could just say they were wasteland warriors, whereas this one was very well thought out in terms of the fact that the groups had segmented themselves and the how deep the cultures went.” In this film time had gone by and cultures had been formed with very distinct identities.

One of the hallmarks of the film was the production’s decision to build as much as it could in real terms and not have for example CG cars. Taylor is absolute in his opinion as to one of the key forces for this approach. “Colin Gibson is probably one of the Australian film industry’s most significantly unsung heroes. He was the production designer on the film and he has worked with George for a long time.” Taylor credits Gibson as being a primary force in having a physicality to the film – “to get something made, create something unique and build incredible vehicles. At some point the ephemeral has to be turned into the physical and Colin Gibson is a truly extraordinary filmmaker in that respect -he is fearless in the face of challenge.”

While Taylor does not see the mythology of Mad Max as being as deep as say Lord of the Rings, “it has a mythology as deep as any film that has ever been made – as the fourth part or sequel to a film,” and he points out this mythology does not stop with the director or the writers. “The fans have generated a mythology between the films that has kept the series alive.”

Taylor sees the fans enriching the film’s mythology, but also the actual world car culture having been influenced by this franchise. “The car culture of the western world arguably wouldn’t be what it is today without Mad Max. It is a very blurred line today between what is real and what is cinematic, and I thought George handled it to near perfection, where he has elevated that culture. So Mad Max has gone from a microcosm of a man and his car trying to save his wife, to a man and his car trying to save a community – to this film where a man and his car try to preserve the human race.”

For the team Miller reclaimed the post-apocalyptic genre, having so artfully defined it from the original films. “George needed to out do George,” explains Taylor, who goes on to remark that those new to the Mad Max films might otherwise have felt this film derivative when Miller’s own films helped create the genre. “And I thought he delivered,” adds Greer.

Part of this aesthetic reclamation came in terms of the film’s saturated palette. Around the time the Workshop team joined the creative process, much of the work had been in the palette of the second film, and it was at about this time that “George decided to bring color to the film very strongly.” Greer sees the color changes as “absolutely brilliant” and all about the emotion Miller was scoring to the action, in terms of “matching tone”.

For Greer, he was thinking about color in terms of the tribes – “Gastown, Bullet town and the Citadel”. It was important see how the various tribes approached their cars, and even how they dealt with their Warboys “as all the groups had Warboys of some form or other for protection, but in say Bullet town they are dealing with sulphur and for with things used for making ammunition, so we wanted that yellow patina on their Warboys, their makeup, the way they they adorned themselves. Their tribal way and importantly the way they treat their cars. It ‘is Bullet town’ – you can read it from a distance.”

“Compare that,” notes Taylor, “to the Citadel where moving up there is first the black grease across the forehead, and the death’s head, the Immortan symbol (Immortan Joe, being the primary leader and antagonist), leading up to the lush nirvana on top of the Citadel. To reach the Dome was to reach nirvana, you reached heaven, this sun drenched oasis. You have transcended, but to get there you have to go through the ‘Denizens of Hell and the tunnels of the Warboys.”

“It is the iconography of Heraldry, the British knights of the 14th century to 16th century,” adds Taylor. “They had incredibly vivid and bright heraldry with extraordinary tapestries and iconography to portray their ‘house’. Well it is no different with Mad Max, the bullet boys are the modern knights of this post-apocalyptic world – drawn together under the single banner of the heraldry of their tribe – and that heraldry has to have color, iconography, typography, graphics – and physical manifestation in the form of the steering wheel.”

There had of course already been a lot of work done before Weta Workshop joined – the team in New Zealand would be the first to say that their role was one of collaborators with the outstanding art department working in Sydney and who would take this work on set. The Workshop was invited to join the onset team but had to decline due to other pressing work commitments, but one gets the sense that the film has taken a special place for the designers who actually got to “tap into their inner bogan.”

Normally extreme designs stay on the page but not so for this project. As Greer summarizes: “This is that process where we get to say what if? We get to sit there and watch insane machines being built. If we design something cool then those guys in Sydney might actually build it. It snow balls into where you are just so excited. For me it is when on a film you can tell the people who are doing it just love it versus it just being a job. On this film, from the top on down, people wanted to work on this film, they wanted to make this film, it was what we grew up on.”