fxguide delves into the tech and artistry behind Walt Disney Animation Studios’ latest feature Frozen and the development of a new tool called Matterhorn for deep snow. Plus we look at how Frozen’s accompanying short film Get a Horse! re-imagines the days of Disney old.

How Matterhorn was made

Amongst the many challenges faced by Disney in creating the Chris Buck and Jennifer Lee-directed feature Frozen was how to deliver shots of heavy and deep snow that both interacted believably with characters and had a realistic sticky quality.

Above: watch a video demonstrating the research behind Matterhorn – “A Material Point Method For Snow Simulation.”

“We looked at all the SIGGRAPH and graphics papers we could find,” says Walt Disney Animation Studios principal software engineer Andrew Selle. “There was a lot on accumulation of snow, making snow drifts, but there wasn’t a lot on the simulation of character-sized snow.”

Previous efforts in simulating and animating snow typically relied, then, on using a rigid bodies, particles or fluid sim approach. “When you chose one of those,” notes Selle, “you made your snow look kind of like that quality. So if you chose fluids and made it viscous, it couldn’t really chunk up. If you made it into rigid bodies, you made it into this pre-sized chunks that you would see. And if you did it as particles, it was difficult to get the volume of snow.”

What Disney wanted was the ability to have a more ‘all-encompassing’ and organic tool that provided snow effects but didn’t require switching between different methods.

Disney’s Frozen toolkit

Along with Matterhorn, Disney employed a host of tools designed to help artists complete Frozen’s complicated effects.

Tonic – enabled artists to sculpt their characters’ hair as procedural volumes. Elsa’s hair, for example, contained more than 400,000 CG threads.

Spaces – Olaf the snowman’s deconstructible forms could be moved around and rebuilt in this software.

Flourish – allowed for extra movement such as leaves and twigs to be art-directed.

Snow Batcher – this tool previewed the final look of the snow, especially when characters were interacting with an area of snow by walking through a volume. Matterhorn would be called upon for highly detailed shots.

The search for a snow simulator actually began as an intern project at Disney in which a researcher looked to simulate individual snow particles in a smarter way. Although that method was not adopted, the research within the studio eventually led to a new academic collaboration and the result was this: a usercontrollable elasto-plastic constitutive model integrated with a hybrid Eulerian/Lagrangian Material Point Method.

So what exactly is that? Andew Selle explains:

“Firstly, if you do fluid simulation, you use something like a grid, and it tends to be the optimal way of solving the fluid. If you want to simulate a piece of cloth, you use a mesh and you simulate that mesh with collisions. But what the material point method does is that it uses mesh or particle-based things combined with grid-based schemes. It’s a hybrid scheme. Through that hybridization, it can do everything OK, but it can’t do everything really well.

The basic assumption we had is that we can model snow as elastic and plastic material. So this is similar to a piece of toffee, where you stretch it and you pull it so far that it doesn’t return. Similarly when you bend metal, that’s a plastic thing. This is something you see with snow, because you can kind of pull snow apart or you can compress it together and it doesn’t return to its original shape. It remembers that shape. So we knew that the plasticity was important.

The thing that’s different about toffee – when you stretch it, it doesn’t break very easily. It can make these long tendrils. Eventually it will. But snow will break into chunks. The material point method comes in here. Since snow doesn’t have any connections, it doesn’t have a mesh, it can break very easily. So that was an important property we took advantage of.”

Disney worked closely with researchers at the University of California on the tech behind a snow simulator that would become Matterhorn. The result, initially, was a paper published at SIGGRAPH 2013 – A material point method for snow simulation. Out of the research, Disney developed a material point simulator that could be implemented in production on Frozen. “We created a Houdini plug-in so it could be implemented with the tool that the effects animators use,” explains Selle. “Houdini is already able to handle millions of particles – we could optimize and parallelize it to make it handle things efficiently.”

Selle notes that Matterhorn came into play for several key sequences in the film. “One really interesting sequence is where Anna is stuck in the snow and is pulled out by Kristoff,” says Selle. “There you see him walking through and see his footprints breaking the snow into little pieces and chunk up and you see her being pulled out and the snow having packed together and broken into pieces. It’s very organic how that happens. You don’t see that they’re pieces already – you see the snow as one thing and then breaking up.”

Another Matterhorn shot was Anna falling off her horse and becoming stuff under a tree. “She tries to use the tree to get up,” recounts Selle. “She pulls on it but the tree is folded over and stuck like a slingshot. It ricochets up and shoots a whole bunch of snow in the air, then a huge pile of snow falls on top of her. It was probably the most art directed Matterhorn shot. We changed what the initial snow shape was. It’s similar to how you art direct fluid simulation shots – you have a collision object underneath the snow mass that pushes kinematically and allows you to get shapes that you would like by pushing the simulator along.”

The more Disney’s artists used Matterhorn, the more they discovered its advantages. “There’s a shot where the ship is turning over with Kristoff riding through the ice field in fjord,” says Selle. You see the snow tumbling off of it. Matterhorn was robust enough to use in these large scale shots as well, and didn’t require any additional tuning. It worked for ‘free’. We even used it for a shot with dirt in the movie. They’re with the trolls and they’re about to marry them and they dig the marriage pit – that was a Matterhorn simulation.”

Art directing snow

Although Disney had several tools for snow effects at its disposal, the studio was still able to look to more traditional methods to achieve a more art-directed look when necessary. “Myself and several other artists in the effects department have a 2D background, and in some cases we did draw-overs,” says Walt Disney Animation Studios effects supervisor Marlon West. “Then we’d bring some of those paths into Houdini. Especially when the floor freezes with ice – most of those were hand-drawn effects that we actually projected and extruded to give them thickness in 3D.”

The technique was also used so that 2D artwork drove the final look for the freezing fountain, and for a sequence in which Elsa is singing ‘Let It Go’ and making snow sculptures. “We had some very specific vis-dev art that the directors really liked,” says West. “We hit that very closely but they were a little too straight-edged. We ended up picking an approach that was more graphic and 2D-designed. They would then start being affected by the wind and start dissolving off.”

Above: watch ‘Let it Go’.

Giddyup with Get a Horse!

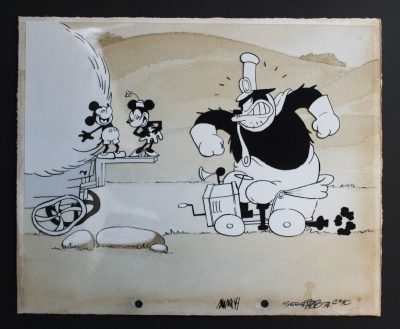

Frozen audiences have also been expressing their delight with the accompanying short film Get a Horse!, a 2D/3D hybrid presentation that begins in the theme of classic Mickey Mouse and then bursts into color, literally, from the screen – an effect further enhanced in stereo.

The short was directed by Lauren MacMullan and represents 18 months of work within Walt Disney Animation Studios from a crew of around 125. “We’re really one of the only studios to have both hand-drawn and 3D-CG artists,” notes Get a Horse! producer Dorothy McKim. “On this film they worked so closely together, and in the screen credits, we put them altogether in one group. We never thought of them as two separate departments.”

Watch a clip from Get a Horse!In order to replicate the look of the classic black and white Mickey Mouse, the studio researched shorts created between 1928 and 1946. “We wanted to make it feel like you were back in 1928,” says McKim. “We essentially had to train our artists away from perfection and do things like not register Minnie’s feet to the ground. There was also a ‘film damage’ pass added which had film lines and dirt.”

The stunning reveal as the characters jump in and out of the screen going around in a circle onto a stage required meticulous co-ordination between 2D and 3D. “We drew everything on paper and cleaned everything up on paper too first,” explains McKim. “On the shot running in and out of the screen in the circle, we had Adam Green our head of CG animation and Eric Goldberg our head of 2D animation work together. I think in one day they passed that shot back and forth to each other four times.”

The filmmakers even mocked up one of their story rooms with a miniature stage complete with curtains to serve as reference. “We got a rear projector to show what it would actually look like when they come on the screen,” says McKim, “and then once they pop out of the screen, to make it feel like it was an old-time movie projector. Then we did a lot of camera work with that research to make sure we could actually translate that onto the screen.”

The filmmakers even mocked up one of their story rooms with a miniature stage complete with curtains to serve as reference. “We got a rear projector to show what it would actually look like when they come on the screen,” says McKim, “and then once they pop out of the screen, to make it feel like it was an old-time movie projector. Then we did a lot of camera work with that research to make sure we could actually translate that onto the screen.”

“And we knew right from the beginning this would play right into stereo,” adds McKim. “When Mickey pops out of the screen onto the stage, we had to make sure that stage was just right, so that when you’re in the theater it looked right. Most movie theaters don’t have a stage, so we had to do test after test by going to different theaters to make the platform/stage look right in stereo.”

The short’s throwback to Disney’s animation heritage extended not only to the final look, but also its sound. As it turned out, Walt Disney Imagineering had a library of authentic sound effects from the 20s and 30s which made it into the film. And even Walt Disney’s voice, itself, features as the voice of Mickey Mouse. “It took our crew three and a half months to pull all the dialogue from 1928 to 1946,” recalls McKim. “We had everything in there except for the word ‘red’. We could not find ‘red’ anywhere. So our associate editor went through and pulled a ‘arr’, ‘eh’, ‘deh’ out of Walt’s dialogue and created the word red!”

Pingback: Behind the Scenes: How Disney Blew Up a VFX Snowstorm in Frozen

Pingback: Why it Matters: Disney’s Frozen | Cinema Confessions

Pingback: Is Pixar Sacrificing Originality For Money?

Pingback: It’s Snow Time..

Pingback: Frozen– 3D animation research | kcimgdsiampatterson

Pingback: The Foxer | Rock, Paper, Shotgun