They may be airing on the small screen, but a raft of recent TV series certainly contain impressive, complex and feature quality visual effects work. We break down some notable VFX shots from The River, the Titanic mini-series, Inside the Human Body and Underbelly: Razor.

Scaring up effects for The River

The eight part ABC series, The River, which aired earlier this year, contained almost 700 visual effects shots by Encore Hollywood. From CG dragonflies to monkeys, characters who are set on fire, and even a flying twig monster, the show delved very much into the paranormal. Although all of the work was completed before the episodes ran, Encore still had to deal with a significant number of shots with a ‘found footage’ and handheld approach – which means the series was acquired often on Canon 5Ds and 7Ds, the Sony EX3 and even GoPros.

“We went into it knowing that,” says Encore VFX creative director Stephan Fleet, who was also the on-set effects supervisor for The River for seven of the eight eps. “So we came up with a workflow early on to combat that shooting style. We made the decision to not use any greenscreen and pulled the trigger on doing full roto and relied on one of our talented 3D tracking artists. But we still had to deal with all the rolling shutter and degraded picture quality issues.”

Filmed in Hawaii, The River made use of practical boats and effects, but Encore was called on to enhance several environments. “The river they used was very small,” notes Fleet, “and there were a lot of technical issues with floating the boat back and forth. We’d have to remove extra boats, and change the mountains in the background to make sure it didn’t look the same all the time, and we widened the river. In one episode, too, there’s supposed to be two boats next to each other but it couldn’t fit, so we added it in digitally.”

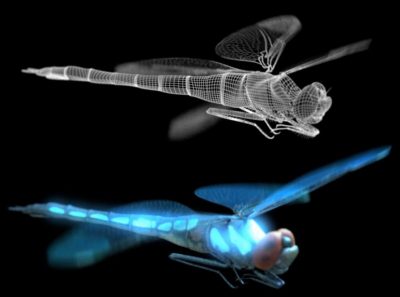

The dragonfly, a recurring creature during the series, was originally proposed as a background character. “We studied real dragonflies and came across a cobalt blue dragonfly,” says Fleet. “We first modeled and lit it and it looked exactly like the real thing but everyone said that it must be fake. But really it looked fake in real life!”

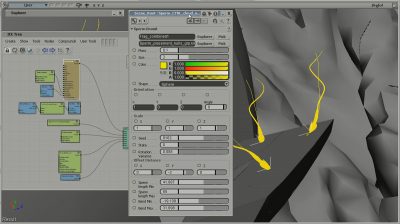

Other CG creations by Encore include a monkey (shot with a stand-in child), a river snake complete with Naiad water sims, and a transforming CG jungle – which features in the show’s final shot. “Initially we took a Maya approach to that and it just wasn’t feeling right,” recalls Fleet. “So we put a bunch of FX people on it and they crafted a particle based sim, then used a plugin for Max that lets you grow trees. The other thing was asset and data management with billions of polys. We had to break up the scene to sub-scenes in Max.”

Monkey progression.Another feature of Encore’s work, despite the usual tight TV deadlines, was the ability to try out new approaches, such as deep compositing and point pass re-lighting in Nuke which were used, for example, in a burning man shot. Fleet also adopted a quick approach to the film’s digi-double requirements. “One of the coolest techs we used was Autodesk’s 123D Catch – a cloud based rendering system. On set, if you take about 30 photos of someone’s head while they’re standing still from an array of angles, it will very quickly combine that into a CG bust to scale. We’ve been using that a lot here. We created CG doubles of everybody in the show and it took 15-20 minutes for each person.”

Back to Titanic

ITV’s recent four-part serial Titanic marked the famous ship disaster’s one hundredth anniversary. To help tell the story of its doomed voyage, Rocket Science VFX’s Tom Turnbull oversaw the series’ 500 visual effects shots. These were completed by Rocket Science VFX, SPIN VFX, Digital Apes and Vertigo. “It was a very character-driven script that also focused on the class system,” says Turnbull. “So we decided to use that and keep it very much with the characters. Nobody had really done it before from the perspective of, say, some poor person treading water hoping to survive.”

Filming took place in Hungary, both at Stern Studios where a Titanic set and water tanks were built, and by the Danube for scenes of the ship leaving Southhampton (filmed with only a few greenscreens and gang planks but filled out with a CG ship and background enhancements by SPIN). The series was shot on the ARRI Alexa, with Turnbull shooting as much practically as possible. “I’m a big believer in elements,” he says. “My background is in camera so I’m very comfortable acquiring elements. We would shoot elements for smoke, crowds, water. The elements set the standards for the way things should look – benchmark for anything CG – the CG people had to look as good as the real people.”

At Stern, production built Titanic set pieces, including the promenade and boat decks, that would later be extended by Rocket Science VFX with wider views of the ship and water. An extensive scan of the set by Plowman Craven, and HDRI’s, helped facilitate the extension shots and greenscreen composites. “We also shot with as many tracking markers as possible,” adds Turnbull. “And we photo-surveyed the set to death. If I’m out supervising a show and I don’t come back with 5,000 pictures then I haven’t been doing my job.”

The extension shots were made somewhat challenging by the fact that the filmed sets were in slightly different proportions to the real ship (and what was being modeled in CG). “The practical decks were built largely accurately to the ship, but had various changes,” recalls Turnbull. “For example, the width of the deck where the boats were deployed was a little larger with more floor space and the life boats were smaller than the real ones. The height of the deck houses were also a little higher and the actual decks of the real Titanic were not flat, but the sets were. We had to massage the geo between the two and find ways to marry them up, using the stacks to make sure things were kept to scale.”

– Above: watch a breakdown of Rocket Science’s VFX for the show.

Rocket Science’s other major contribution was the iceberg impact. “It was described by someone after the sinking as the Rock of Gibraltar,” says Turnbull. “So we took that idea and built a physical model of it. The first version looked too much like the Rock of Gibraltar, so we re-modeled to keep the general character but not similar. It was modeled in clay, then cast it in fiberglass. We had it scanned and that’s what we handed off to the 3D guys as a dense mesh of geometry to be rendered in 3Delight. They’re pretty opaque, icebergs, and frosty looking but there is a bit of scatter that goes on – you see it in the deep crevices – so we approached it like that.”

For ship scenes, Turnbull looked to SPIN VFX to model and animate a digital Titanic. One of the overriding principles was that the exterior shots of the ship at sea had to look like a ‘floating palace’. “There’s a definitive line in the book A Night To Remember,” says Turnbull. “They described it as a sagging birthday cake, implying its grandeur was being eroded away. We definitely had that in mind as we were doing most of the shots – that it looked as much as possible as the floating palace, so that when we started to sink it in the water it continued to be damaged.”

To aid SPIN’s visual effects for the digital Titanic, Turnbull provided significant reference and the team looked to period photographs and books. 3ds Max and Maya were then used for modeling, with Photoshop and Mari for texturing, PFtrack for tracking, Maya for animation, RealFlow for water sims, RenderMan for rendering and Nuke for compositing.

“Our biggest technical challenge was the hull,” says SPIN visual effects supervisor Colin Davies. “Specifically, getting the pattern of overlapping plates to work at all distances. We ended up having to model in all of the plates in order to get the detail we needed. It was a real challenge to maintain those hard edges but also have the large-scale sweep of the hulls compound curves hold up at very oblique light angles.”

“The rivets, portholes and mooring cleats were created procedurally in the shader in order to reduce the amount of geometry in the model,” adds Davies. “Most of the look of the hull was created using custom procedural shaders creatively combined in Nuke. We did use some painted textures for close shots but that was the exception. When we did use painted textures, Mari was a real asset. We implemented late in the production but it really helped out in a few shots where the camera sweeps in close to the ship and we needed the extra detail.”

Water, foam and smoke were simulated in RealFlow and combined with large-scale smoke elements shot by Turnbull. SPIN also created debris sims for when the Titanic breaks apart. For passengers, the solution was a mix of greenscreen extras and digi-doubles. “We key framed the passengers in the sinking sequence due to the inclination of the ship and the specific actions we needed,” says Davies. “We used the 2d elements for all other shots with passengers.”

The crane shot showing the passengers boarding at Southhampton was one of SPIN’s most challenging. “It was the first time we got a close look at the ship so we had to make sure it looked totally believable and supported the mood of nostalgia, awe and foreboding,” comments Davies. “The plate was shot on location in Hungary with a green screen backing that covered all of the actors and most of the slowly rotating cargo net in the foreground. We tracked the ship and used onset HDRI for the basis of the lighting. We get so close to the hull here we did paint in some additional hull detail and then spent a great deal of time in comp getting the feel just right. This served as the key look shot for the ship in daylight and was well worth the effort.”

Award-winning effects for Inside the Human Body

Jellyfish Pictures’ work on the BBC series Inside the Human Body won the Outstanding Visual Effects in a Broadcast Miniseries, Movie, or Special (Phil Dobree, Sophie Orde, Dan Upton) at this year’s VES Awards. The studio’s effects were predominantly seen in the series’ first episode ‘Creation’ which follows the story of conception inside the female body.

“The BBC were very clear, as were we, that this should be different to anything done before and should be immersive and narrative rather than explanatory and dry,” notes Jellyfish creative director Phil Dobree. “I was clear that we should make the sequences narrative and led from an animation story telling perspective rather than dry, as this hadn’t really been done before extensively on internal sequences on television. It meant finding the stories in our bodies that allowed the CGI to do this, then going out and finding real life stories that backed these up. The science needed to be accurate, but the final visual images needed to be wondrous and immersive and the look definitely led the narrative in this sense.”

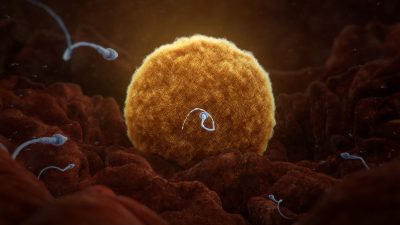

For reference, Jellyfish drew inspiration from the photography of Lennart Nilsson. “We got some fantastic concept art and storyboards drawn up for the sperm to egg sequence that would help provide us inspiration for the series look,” says Dobree. “We thought the best approach would be to limit the camera moves thus giving us the opportunity to use digital paintings and CG models that worked fantastically from certain angles but didn’t need to work from all angles. What was particularly helpful was to avoid shots that went from wide shots down to macro shots – always a difficult and time consuming process in CGI. By using cuts, camera drifts, slight pans and tilts we were able to create a series of beautiful images in CGI that looked complex and had a lot of depth.”

Progression for egg shot in Inside the Human Body.In one shot, as the sperm break the corona of an egg, artists blocked out the animation in Softimage with simple geometry, then took the scene in 3ds Max to add extra detail and procedural animation effects. “We then enhanced the surface with a combination of manual and procedural modelling,” explains Dobree. “We extracted a part of the surface which intersected with the sperm, cut the geometry up, ran a cloth simulation. We made the surface into a volume which was then filled with millions of particles. The particles near the intersection were attached to the simulated surface then in particle flow we set up a system where some of the particles would break away and then would be moved into a Fume simulation which created the effect of the sperm churning up the particles.”

“We also ran other simulations of particles being ejected and floating around,” continues Dobree. We would normally render a depth pass and add the lens effects in comp but due to the complexity of the particle surface it had to be rendered with 3d depth of field and motion blur. In the comp the 32bit images from Krakatoa were altered greatly to create the look we wanted and we then added the larger out of focus particles.”

Jellyfish would then render out some key images from the shots, bring them into Photoshop and paint them up to be projected back onto geometry. “This allowed us to create complex images and render the backgrounds extremely fast, which freed up more time for complex simulations,” says Dobree. “Slowing cameras down and avoiding crazy ‘just because you can’ clichéd CG camera moves helps to create a more cinematic feel. This was a deliberate stylistic approach from the very beginning and was deliberately decided before any work was started.”

Building a bridge

For the Australian TV drama Underbelly: Razor – a show set in the 1920s and 30s in the Sydney underworld – Digital Pictures was called on to feature one of the city’s most iconic landmarks under construction: the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Artists looked to several sources for reference imagery and video from the era.

“Google is always a prolific source of documentation of course,” says Marcus Bolton, Head of Post Production and VFX Supervisor at Digital Pictures, “and if you do an image search you would be surprised by the amount of period pictures that are available. Fortunately, the building of the Harbour Bridge was quite well documented, and the National Library of Australia’ was quite rich in archive pictures, as well as NSW State Records which was very useful and well documented with an online research engine which allows you to access pretty much anything.”

Digital Picture’s VFX team built a Harbour Bridge model in Maya initially intended for background scenes. “We were quite confident that we could shoot with pretty much any angle as long as it was kept as a background or illustration,” recalls Bolton. “The budget wouldn’t really allow us to film a real construction scene occurring with cranes and tradesmen. Having said that the film crew captured some footage with the actual bridge shot from around 500 meters and the substitution between new Harbour Bridge and the construction bridge worked out beautifully.”

“Once the background plate was shot,” adds Bolton, “our matte painter team would then position the 3D model of the Harbour Bridge accordingly and started texturing it. A beauty pass was then provided to the compositing team to finalize the shot with camera projection on the 3D model if needed.”

For recent coverage of visual effects in other TV shows, check out our feature articles on Terra Nova, Breaking Bad and season two of The Walking Dead. And we’ll soon be highlighting Pixomondo’s VFX for season two of Game of Thrones, and Tippett Studio’s impressive VFX work in Hemmingway & Gellhorn.