We take a look at the visual effects in Tim Burton’s latest film, Dark Shadows, talking to overall VFX supe Angus Bickerton and showcasing the work of MPC, Method Studios, The Senate and Mattes and Miniatures.

The ideal approach

Old school

This film is a modern version of a classic TV show, modernized and updated for the present. As were the visual effects.

This film is a modern version of a classic TV show, modernized and updated for the present. As were the visual effects.

The film was shot on film (and not shot in stereo nor converted to stereo). The DOP Bruno Delbonnel, (Amélie, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince) shot the whole production on film so the various effects houses had to match film stocks, grain and look. The stock was 500ASA 5219. Peter Doyle (Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings) was the supervising digital colorist, Doyle and Delbonnel having worked together on The Half Blood Prince. (Note: some of the example images in this article are pre-final grade).

The film was set in the past, and whenever possible the filmmakers used traditional well executed VFX methods, but like the film’s central plot line, even the old techniques were brought forward in time with the addition of the latest effects techniques.

Thus it is that Dark Shadows – a story about a man out of time – has miniatures, over cranked shots, recorded at high fps, actors filmed under water for zero gravity effects, hardly any previs and it was all combined with cutting edge camera projection, complex fur tricks and painstaking attention to detail – that extended to removing every blink of Johnny Depp’s eyes and every hint of his reflection from hundred and hundreds of shots.

The film is based on a TV series that was not itself a comedy, explains VFX supervisor Angus Bickerton. “It evolved a bit from the TV series, the TV series was never intentionally funny, it was this slightly strange gothic soap that ran three or four days a week early afternoon – just in time for Tim Burton and Johnny Depp to get home and watch it!,” he jokes. “I dont ever think it was intended to be funny, and when I read the script for Dark Shadows, I imagined – you know, Tim Burton – dark gothic with tinges of humour, but I think more fun came out of it as it evolved”.

The film is based on a TV series that was not itself a comedy, explains VFX supervisor Angus Bickerton. “It evolved a bit from the TV series, the TV series was never intentionally funny, it was this slightly strange gothic soap that ran three or four days a week early afternoon – just in time for Tim Burton and Johnny Depp to get home and watch it!,” he jokes. “I dont ever think it was intended to be funny, and when I read the script for Dark Shadows, I imagined – you know, Tim Burton – dark gothic with tinges of humour, but I think more fun came out of it as it evolved”.

Angus Bickerton, VFX supervisior

For a lengthy in-depth discussion with Angus Bickerton, listen to our fxpodcast.

Miniatures

Almost a main cast member in the film is the family manor house in the mythical town of Collinsport. This house was based on a real estate house north of New York that was filmed for the original TV series. “I knew within the space of about three minutes of talking to Tim,” recalls Bickerton, “I literally got the script and went in for a chat with Tim, didn’t chat for very long – 15 minutes – and the first thing he said was, ‘How do you feel about miniatures?’ And I said, ‘I love miniatures – I think they are great.’ And he said, ‘Well I think we are going to have to do some in this film – I think it is appropriate to the style of the film'”. And Bickerton agreed completely. “So there was no hard thinking about that… the only thing I ummed and ahhed about was 1/4 scale or 1/3 scale.”

The mansion was built by Mattes and Miniatures, ultimately at 1/3 scale. The team calculated the real building was “about 100 feet to the very tip of the tallest tower so yeah – it was a bigature,” notes Bickerton.

Rick Hindrick designed the house and very much referenced the original building from the TV series. The house as seen in the title sequence was shown as a day for night shot of a real house and that house is an actual mansion north of New York. In later series they may have used a different house. But the film references the first series house.

While the team could have used motion control to match the live action plates to matching scaled photography of the ‘bigature’ they decided against it for a number of reasons:

- the camera work would match better using projection

- motion control would slow down main unit

A few years ago that would have been the way to do it: “film the live action – track the live action and the solve the live action and program the scaled mo-co move,” says Bickerton. “But you just know these days that there will be Steadicam and that you are going to have to extend via a Technocrane.” The problem Bickerton points out with scaling such dynamic moves is that tiny bumps and imperfections in the live action don’t scale well down to motion control. “The rig can’t do such tiny bumps and moves and thus they are filtered out, (at any normal speed), and today there are more choices. I opted fairly earlier on that we would take camera measurements, a survey, good camera notes (camera start and end heights, lens info etc) and then we would plot it out and do a mix and overlay. Sometimes I would do a best guess pass, sometimes I would just shoot a start and end of the move, all with the intention that we would image project to the match move.”

Filming the miniature to match the lighting is clearly extremely helpful. The miniature was set up at a new film space/studio near Longcross studios not far from Shepperton studios. The primary set was just outside London and it was just the front facade. “If you looked into the house (in the film) then the shot was a composite,” says Bickerton, since the door on set lead to green screen and the interiors were added in post.

“We built a flexible miniature shoot schedule to match the lighting, and the miniature was built so that it was in the same (compass) alignment as the ground floor set, but allowing for it being 4 months later,” explains Bickerton who earlier in his career had worked with UK miniatures expert Derick Meddings (1931 – 1995). Meddings was a British television and cinema special effects expert, initially noted for his work on the ‘Supermarionation’ television puppet series produced by Gerry Anderson, and later for the 1970s James Bond films and the Superman film series. “His favorite ploy was always to build a miniature and film it outside,” says Bickerton, “and let God do the lighting and that is what we did. We built it (up) on a 12 foot rostrum and aligned it so that it was in the same alignment to the sun as the original set in Bournewood, taking into account that it was four months later.”

In an interesting aside, Derick Meddings worked with Tim Burton on the 1989 Batman. Meddings later said before his death that he thought Burton invited him to work on the film due to his work on Thunderbirds, of which Burton was a fan. Bickerton also worked on Batman as a motion control cameraman. This live action SFX camera background clearly served Brickerton extremely well on Dark Shadows.

Shooting a large scale miniature outside has several advantages:

- the light is parallel and not as a cone shape as happens from a close point light

- the light is very even in sunlight, the inverse square distance law is irrelevant. An actual light on set would mean one end of a miniature is closer to that light will be at a higher f-stop than a further away part of the model but sun light it is all even (due to scale and distance to the source) so the f-stop is even across the model

- a large amount of light means one gets a great f-stop in light levels to help with having a high fstop and thus deep depth of field

- the lens is also normally wider on the miniature to match the camera and “you tend to be on the infinite end of the lens and there is something that really makes a difference about filming at the long end of the focus,” points out the experienced Bickerton.

Fire

The Collins manor house burns in the climax of the film. Once again the miniature was used. The team shot for a week and half of the miniature and then the miniature was burnt. Mattes and Miniatures rigged the whole model they built. Bickerton had earlier seen a burning miniature done by Mattes and Miniatures for the film The Wolfman. “I was really impressed with the flames on that,” he says. The miniature manor was rigged with gas flame lines, and the collapse was rigged. There was a basic previs of where it would burn that was shown to the director, before the model was burnt. “It was all rigged and then it was a one shot gag!”

The Collins manor house burns in the climax of the film. Once again the miniature was used. The team shot for a week and half of the miniature and then the miniature was burnt. Mattes and Miniatures rigged the whole model they built. Bickerton had earlier seen a burning miniature done by Mattes and Miniatures for the film The Wolfman. “I was really impressed with the flames on that,” he says. The miniature manor was rigged with gas flame lines, and the collapse was rigged. There was a basic previs of where it would burn that was shown to the director, before the model was burnt. “It was all rigged and then it was a one shot gag!”

Leigh Took (DaVinci Code, Lost in Space) was the SFX / Models Supervisor at Mattes and Miniatures. Took started in the industry as an apprentice learning the classic techniques of matte painting, and miniatures, at Pinewood Studios for over ten years, working on many major feature films. He then left Pinewood and went freelance to work with the late Derek Meddings (at Magic Camera Company) on Burton’s Batman which is of course where he also met Bickerton. Took did multiple shots of Gotham City for Batman along with Mark Gardner and Pete Talbot (who was DOP of the splinter unit on Dark Shadows). Also part of Meddings’ team was “Angus Bickerton (Dark Shadows VFX Sup), Peter Chang, (who went on to be VFX Supervisor on John Carter, Bourne Ultimatum), Steven Begg (who went on to be VFX sup for Skyfall and Casino Royale) and Neil Sharp (Brazil),” recalls Took recounting the amazing talent director Tim Burton brought together on the 1999 Batman.

Took has a long career in matte paintings in addition to miniatures, specifically with Cliff Culley (Dr. No, From Russia with Love, Goldfinger, Thunderball, You Only Live Twice, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang). Culley took on some miniature work, and Took got to work along side Ray Harryhausen, (The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, Jason and the Argonauts). Harryhausen literally filmed his animation next door to where Took worked, so Took would often quietly watch the great animator work.

For Dark Shadows, Took explained that miniatures, like the Collinwood manor house, are very much like a matte painting, in that much of what works in a matte painting is the illusion of detail, not just actual fine mechanical detail. “With a miniature it is almost like a matte painting, you can play around with the depth and it is like a 3D real matte painting,” he says. “It is the same thing, you are creating an illusion. I am 52 and I still get excited about it – which is good!”

One of the challenges of building the manor model was the need to burn it down. This meant that it needed to be built in such as way that would both burn correctly and not reveal its miniature construction techniques. For example, a non-burning model could use pins to hold things in place, but these would be revealed in a burn.

The building had to be made to partially collapse. To achieve this the team built the model with:

- Specially made lead light windows, so the lead between the tiny panes would ‘melt’ causing the glass to fall separately

- The building was rigged with internal weights and drop lines that would cause roof and sections to fall and collapse – timed by the nature of the melting and burning temperatures of the material used

- Debris dumps were hidden in the tower and released by timed burns to fall on cue

- The turf grass in front of the house on set had been laid, but due to hot weather had dried out and so Burton did not like the live action grass. Miniature green ‘fun fur’ yarn / grass was added to the front of the miniature, raked with hair gel and then sprayed with fire retardant so it could be used and have falling burning elements hit it. Some real plants were used, which Took laughingly pointed out “got a bit burnt but we still have here at the office, and they’re all surviving”

- The curtains needed to burn behind the windows, so Took and the team at Mattes and Miniatures built false rooms behind the windows

- For the tower and roof collapses, there was internal dressing and structure revealed. Specific roof tiles were held with materials that would melt sooner, allowing for those roof tiles to slide and fall earlier, while other areas were made with an acrylic plaster ‘jesmonite’ which is a non-toxic unlike fiberglass. Jesmonite is a gypsum-based material in an acrylic resin that burns at a very high temperature but can be made to look like stone, yet is extremely light weight.

Unlike some other crafts, however, all the physical work of this miniature at the end of the day “was pushed into a skip (bin), but when you look at rushes it is all worth it,” says Took. “We were looking in a van with Angus when we were reviewing next day rushes. Angus put this stuff on, and some of our material of the door way and we couldn’t even tell it was our model at first, of course a lot of credit needs to go to the lighting.” The burning model had been lit be a high soft balloon light, to mimic moonlight, even through the building burns, it would not have been enough, so some ambient light was required, “and that let us see all the detail, the gargoyles, so it did take a while to light it,” Took adds.

Took, while one of England’s most experienced model and miniature artists working today, is very comfortable with the full complement of digital tools. Matte and Miniatures use a host of modern tools, but with the key ingredient of physical textures, elements and photographed elements. Took’s team work therefore integrated extremely well with the digital compositing of the various effects houses and the company exemplifies the blending of old and new that seemed to be at the heart of Dark Shadows.

The company is based at Pinewood and Bray Studios and has a crew experienced in all aspects of designing, constructing and filming visual effects. Digital facilities at the Pinewood base combine the best of traditional matte techniques with the new and the Bray Studios base includes a traditional matte painting studio, motion control, model and special effects workshops and art department.

The interiors of the burning Collinwood Manor were composited by MPC.

Ghosts

In an approach reminiscent of the ghosts in Poltergeist perhaps, the production decided to film Josette duPres’s (Bella Heathcote) ghost scenes in an underwater tank, to gain the weightless ghost like features. The final shot is a combination of a stunt double and the shots of the actress, and CG crabs. Josette DuPres dies in the film and when she returns she needed to walk, fall and attack other characters.

The underwater scenes were shot on U stage at Pinewood. U Stage is used by many different types of productions; over, on, in and under the water. The facility is globally unique, with over 1.2 million litres of water heated to 32°C turning around every four hours. There was a test shot done with a stunt double in the dress and the director really liked the movement of the dress. Bickerton points out that while it looked great there were also disadvantages:

- the artist needs to fight against the water’s viscosity

- they could not move very fast so this meant some of the footage needed to be sped up to look normal

- there is always a need to do extensive paint out of bubbles

- “over the course of about 20 feet you lose the red channel,” says Bickerton, so keying can be really difficult

Bickerton wondered if they could not get something similar by filming an actor sitting or standing above a massive air jet. They also tested this shooting on just a domestic cheap high speed camera and showed Burton. The results were close but this new technique came with its own problems. They needed to over crank the dry footage – the inverse of the water situation.

He liked both tests, the hair was better on the underwater test but the dress better on the air jet approach. In the end the solution was to use both. “The majority was the over cranked dry – air footage shooting at a 120 fps,” explains Bickerton, “but then we got a stunt double in and shot underwater, so on screen you are often seeing underwater hair with dry Bella.”

For Josette DuPres’ ghost to seem to interact with her environment, contact lighting was done on set. Lights on the corridor were achieved by a member of the lighting department moving lights up and down the corridor in a separate pass, these were then combined and projected via geometry on the walls, to give the ghost more presence in the environment.

The digital crabs were quite a late edition to the shots, those were modeled and textured in Mudbox, rigged and animated in Maya by The Senate. The team had to combine the digital crabs with accurate object tracking to the actresses body, to allow them to accurately crawl over body, and in one case out of her mouth.

As she falls and ripples through the floor, the individual tiles were modeled so each tile would have an independent ripple effect that combines to an overall watery feel, to match and reflect the characters own real death earlier in the film.

Josette DuPres’ on screen fall from the chandelier was achieved by having a stunt woman fall back – all under water – shot by underwater cameraman Mike Valentine. The stuntwoman had weights in her dress and weights in her hands, and she actually falls back but only a short fall of about five feet. In mid fall the VFX artists took over and extended the shot to make it seem as if she was falling much further. The element was then stabilized, tracked and placed back in the lobby set as a ‘card’ and the floor and lighting added to feel the shot.

Josette DuPres’ on screen fall from the chandelier was achieved by having a stunt woman fall back – all under water – shot by underwater cameraman Mike Valentine. The stuntwoman had weights in her dress and weights in her hands, and she actually falls back but only a short fall of about five feet. In mid fall the VFX artists took over and extended the shot to make it seem as if she was falling much further. The element was then stabilized, tracked and placed back in the lobby set as a ‘card’ and the floor and lighting added to feel the shot.

The shot took a long time to get right. “Tim kept on saying, ‘You’ve gone too Harry Potter, too Harry Potter, you’ve gone to fancy, I want it nice and simple, I want a nice beautiful effect’ because he thought it was appropriate to the story,” says Bickerton.

Blinking

Barnabas Collins (Johnny Depp) is a vampire and as such apparently never blinks. Thus it was that in 700 shots in the film there was precise blink removal. This was done either by the individual effects houses working already on a shot, or by a special unit set up at the production office by Bickerton.

This was indicative of the attention to detail the team applied. The idea to not have Barnabas Collins blink came directly from a discussion between Johnny Depp and director Tim Burton.

Reflections

As a vampire, Barnabas Collins also casts no reflections. While this was very strongly played in some shots such as when he is brushing his teeth, Collins is not reflected in anything. “As he walks around the set he doesn’t reflect in anything,” explains Method Studios’ VFX supe Mark Breakspear. “He does not reflect in the sides of cars, he does not reflect in windows of shops, in edges of telephones. His reflection is painted out in the entire movie.”

Breakspear jokes that while that may seem like a “gross misuse of visual effects” to some, for Breakspear it is also “quite beautiful and conceptual and in all seriousness it was very cool.”

Cracking up

As the plot and future unravels for Angelique Bouchard, the character starts to crack, literally. The reference Burton gave Bickerton was that of a antique china doll, although the final look took some time to agree upon. The majority of the cracking happens in what the film makers nicknamed the Battle Royal at the end of the film. Burton described the scene as super natural domestic violence. Early on Burton decided that we wanted to be able to later decide how much and how she was cracked, so on set the actress had image markers applied to her but no special effects makeup.

The actress was cyber-scanned and filmed by the primary camera and two witness cameras. The actual cracks were designed as Photoshop art, and it was combined with the actress via complex object tracking. Mocha was used in some shots to get some highly accurate 2D tracking to really lock on to the actress’ real skin. But to avoid it seeming just like a UV mapped tracked 2D effect, the team displaced and moved some of the ‘cracked tiles’ so the effect would seem more dimensional. The on-screen Angelique Bouchard is a combination of the original live action performance of the actress, “with additional blended in match moved 3D of her too,” explains Bickerton.

The cracking was handled by MPC and The Senate.

The Senate

In the film the audience sees the family home of Collinwood manor in all its various states, from run down to re-furbished, and from burning to its original construction at the beginning of the film. While a model was built, The Senate had to digitally provide the half constructed version of the giant manor house.

The Senate started with geometry derived from a LIDAR scan of the full built 1/3 miniature Collinwood Manor. “Once we had that, we could start pulling it apart,” explains The Senate Visual Effects, VFX supervisor Anton Yri. “We (digitally) pulled off the walls pulled off the roof, and modeled the wooden structure – that was all done in Maya, and then once we had that we had to add detail such as ropes, scaffolding, frames. We did a lot of the more detailed modelling using Mudbox.” Not only did the building need to look like it was under construction, but it need to be under construction in the 1800s. “We did quite a lot research for the construction techniques of the 18th and 19th century,” says Yri, “and while we did not have photography from back then, the team did build up a lot of understanding of how building such as this were built.”

The detail extended not only to techniques of layout and approach but also building materials. For example, The Senate tried to get the right wooden sections modeled with shaders that indicated manual cutting techniques and period markings. “It had to be well constructed but we could not rely on them having modern tools to do it,” adds Yri, “everything had to have a slightly rough edge to it and all the wood needed to look dirty and scuffed.” Also, in the film it was established that the building took years to build so the team had to dirty up the exposed materials to indicate they had been weathered during construction, even if they would normally be internal beams or supports.

All of the manor shots also had to also be placed in an American location, given the ground floor set was built and filmed in the UK. Because the film was set on the east coast of Maine, the team added CG trees accurate to the area and further extended the environment with photos from around Maine. The team also added a lot of 2D mist and fog to create the atmosphere of the United States east coast.

Angus Bickerton worked closely with Oscar award winning Production Designer Rick Heinrichs (The Big Lebowski, Fargo, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest). Heinrichs won an Oscar for his work with Burton on Sleepy Hollow (1999). One key area of cooperation between all departments was the canning factories. There is Angel Canning the competition and the original Collins fish factory, which is seen in many states of repair, inside and out.

The Collins canning factory is normally seen only from the outside, but in a couple of scenes it was important to enter the factory, and The Senate helped build one row of cannery workers into three rows back and three rows wide.

The Collins canning factory is normally seen only from the outside, but in a couple of scenes it was important to enter the factory, and The Senate helped build one row of cannery workers into three rows back and three rows wide.

The factory needed to be extended up and back as it needed conveyor belts moving up in the air. Yet the idea was to not make the factory too busy, and too confusing. With the amount of reflective surfaces and additional works, the shots quickly became quite complex. The Senate provided Angus Bickerton with accurate guidelines of which angles to shoot the few extras that were available on set on greenscreen to allow an efficient shoot on set, that would still perfectly match with the complex factory layout.

MPC

MPC delivered 340 shots for the movie, lead by VFX Supervisors Arundi Asregadoo and Erik Nordby.

Nordby’s team at MPC Vancouver were tasked with the completion of 90+ shots. The main focus was on two sequences set in and around a 200 foot high sea-side cliff referred to as Widow’s Hill. It is here that much of the pivotal action takes place between Barnabas and his heroine from each respective time period. Twice in the movie people hurl themselves off the cliff onto the rocks below. But due to the power of the vampire bite, unexpected results push the movie into very different directions.

The cliff itself was comprised of seven large slices of rock-face, all built at different resolutions depending on their usage in the movie. The cliff edge, where much of the action takes place, needed to match a set piece built during production. Several other promontories were then built along the coastline. These were mainly featured in large establishing shots of the area.

For all of the cliff shots a combination approach was taken splitting the tasks between DMP/Env and traditional assets. The rough shape of the cliff was built, and some portions of it were sculpted in Z-brush to help add detail. It was lit in such a way to pull as much topology as felt natural. This was then married with a bespoke set of Env textures that were projected onto the slices.

Above the cliff was a pine forest and the Manor that held the Collins family. The forest was built by seeding individual trees using VUE software and then painting over the top. This allowed a lot of natural variation and parallax on the moving shots. Vancouver was also tasked with creating the large establishing shots of Liverpool that open up the film.

MPC London’s main focus was on the supernatural showdown between Barnabas Collins and his scorned ex-lover, the witch Angelique. All of this unfolds in the foyer of Collinwood manor. The action involved wooden statues (caryatids) coming to life, Angelique’s gradually cracking skin, a vengeful ghost. One of the biggest challenges was depicting the transformation of Angelique into a cracking ‘porcelain doll’. The team worked on over 115 shots showing her gradual calcification and break down.

Of course no horror film would be complete without a werewolf, this time a teen she-wolf, played by Chloe Grace Moretz. Having some experience with CG werewolves (Wolfman, Harry Potter, X-Men: First Class), MPC’s pipeline was well prepared for this work, however Chloe’s design was far more stylized than anything they had previously created. The art department initially, followed by a fairly sharp round of 3D groom and lookdev, were able to create something very close to Tim’s initial vision, and she was rendered, complete with animated wolf legs, in the shots depicting her attempted attack on Angelique during the showdown.

MPC’s DMP, FX and animation departments worked closely on bringing wooden statues to life in the Grand Foyer. As Angelique casts her spells around the house, we see her bring the myriad wooden statues including a serpent and caryatids to life, which are then shot by Michelle Pfeiffer’s Liz and one caryatid even captures Jonny Depp and restrains him for a considerable portion of the edit.

The statues were built with considerable flexibility in their rigs so that they were able to perform a number of eerie movements, some more violent than others. MPC’s Animation Supervisor, Peta Bayley, had her team focus on the statues as a single ‘beat’ of the action and the FX team added ‘breaking away’ FX as the statue tears away from the wall. The DMP team had a crucial role in creating the feel of increasing levels of blood and destruction unfolding in the background. A shorter segment at the start of the scene shows some hero shots, which utilize some lovely live action elements, to sell the idea of the blood emitting from statues and cracks.

Method Studios

Mark Breakspear and the team at Method Studios Vancouver were invited to join Dark Shadows primarily to do environment work, they had previously worked with Barry Hemsley (Production VFX Producer) and Angus Bickerton (the Production VFX Supervisor) before on environment shots. In total they did about 185 shots, with some shared with other facilities like MPC and the Senate.

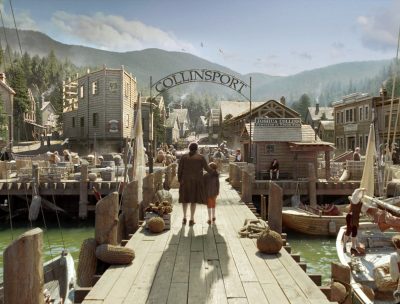

The majority of Method’s work was Collinsport – the fictional town in the film. The movie was being “filmed in London at Pinewood, and it was supposed to be this beautiful little town, on the east coast of Maine (USA), and there is obviously a stark difference between filming on the backlot at Pinewood in a tank and making it look like a coastal village,” says Breakspear. “We shot in the water tank at Pinewood, with an 80 foot blue screen and a partial set build around the key areas and we extended it from there.”

Method also had to wrangle digital seagulls. It was decided early on that seagulls really sold the town as coastal. Breakspear jokes, “We got very very good at creating CG seagulls – if you take a picture of anything, a jar of jam, and add some seagulls in the background, one goes ‘you know I think that looks like it is at the beach.’ You can take anything – a shot of a desk – add Seagulls – it is a desk at the beach. It is an instant recognition, so much so that I am going to write to The Foundry and suggest they make an auto-seagull plugin for any shot that might come up in the future!”

Not only did Method get good at making seagulls, but director Tim Burton got very good at directing them and balancing believable bird action, but stopping short of having the actions of the birds distract the viewer or draw attention to themselves. The CG birds were actually named by the production team. Method did shoot reference of real seagulls – for the animators to use a reference, which consisted of some poor assistant standing on a real pier with a mass of bread while flocks of birds descended upon them – all in front of a Method witness camera, “I think we lost a couple of PAs that way!,” Breakspear adds laughing.

Method also worked on the prologue to the film which has the Collins family leaving Liverpool in the 1800s. This sequence and others required not only digital environments of buildings but also large amounts of digital oceans and water. See below for Advanced Nuke work.

Most of Method’s shots involved replacing the roof or rather adding roofs to the sets that were built, and extending out the town, but two other interesting sequences not directly in Collinsport were also handled by Method, the train station and the first fireplace sequence reflection removal.

Train station: In the story one of the main characters arrives in town via train. On the day the train station was actually a tiny piece of green screen in between two offices at Pinewood. A small amount of station was build and then LIDAR scanned. Method then not only added the rest of the station but the entire train.

Train station: In the story one of the main characters arrives in town via train. On the day the train station was actually a tiny piece of green screen in between two offices at Pinewood. A small amount of station was build and then LIDAR scanned. Method then not only added the rest of the station but the entire train.

Fireplace sequence – ‘Hall of mirrors’: Early in the film Barnabas descends to a secret room under a fireplace. The corridor leading to the room is lined with mirrors, and as Barnabas is a vampire, John Depp’s reflection needed to be removed, while keeping in his companion’s reflection (Michelle Pfeiffer). To achieve this the whole set was Lidar’d, the actors were then removed from the backplate and then added back into a CG environment, with some real reflections added back, but only those of Michelle Pfeiffer and the lamp Depp was holding.

Advanced Nuke work

One of the most advanced Method shots came from narrative story flow and matching camera work. In the sequence where the Collins family leave the UK and head to the US of A, it was discovered in editorial that almost every shot the camera was moving slowly forward with the actors. The sequence is largely a dialogue free montage of shots, in which every shot but one has the camera tracking slowly forward with the actors as they move both across the screen and across the Atlantic. All but one.

In the shot a young Barnabas and his father are walking down a jetty towards the town in 1752. The shot that ends up in the film is a moving/tracking shot and this was done by re building the entire town and the shot in Nuke. It was not done as a CGI build but as a projection build using Nuke’s excellent camera mapping and projection techniques. “Up until this point – in the past, when we had done this sort of thing in say Angels and Demons (2009), it was very much done in Maya and then rendered and composited in either Shake or Nuke,” explains Method’s Mark Breakspear. “This time we really wanted to use everything we could inside Nuke to put this environment together – since environments tend to be really tricky and very heavy – we had trees, buildings, thousands of people layers, dust (and brilliant seagulls everywhere). We built it in a way that worked – it was a heavy render – we were working with 4K plates, because of the amount of projection we were doing (but the film was still finished 2K).”

The final shot follows the actors along, which illustrates the care and precision of the Method team “to do it right we needed to build the entire existing environment, and re-project it in Nuke”. But any projection only is perfect from the original projection point. While projections are very powerful, they do not magically see around corners the original camera did not see. Thus as the move develops, the projection shows up edges, imperfections and seams where there is missing visual information, the result, if left unfixed, is like a giant tear in the image. “We had to go through and repaint everything and so what end up in this sequence, is not only repairs but we added CG boats back in, since in the original composition the frame was balanced but now a gap is revealed as you move forward, and you say to yourself – ‘well if I had really filmed this – I would have put a boat there’ – so we ended up putting a boat there – and people on that boat etc. It was just a very cool development of the shot in terms of a Nuke project – a very big environment that allows you to control all those pieces for a perfect final render.”

As with other sets such as the ‘room of mirrors’ set, the town was Lidar’d. “Lidar is great but getting it to be useful is extremely difficult, and so one of the things we did was write some custom software that would take the Lidar data and import it into Nuke,” says Breakspear. Nuke has a ‘point cloud’ feature but Method found it lacking and not useful on this film. The Method code allows the Lidar to be imported and then used like a positional map or p-pass (pmap) in Nuke. Pmaps provide a location in zspace for each visible pixel, and this in turn has the effect of mapping the filmed footage over a virtual point cloud 3d model of the set. The image looks the same to the viewer at first glance but now each object is correctly positioned in z space or 3D space ready for advanced compositing. This does not allowed for finessed roto, but it helps with expanding the city and providing set extension. In 50% of shots this allowed for projections to be used, projected over that Lidar positioned geometry and furthermore other CG elements could be added. One thing that was needed to sell the modern version of the town was power cables. Here the Method team actually used a fur software engine and used a modified hair (fur) render to actually be the swaying and realistic power lines between telegraph poles. “It is quite funny but we didn’t budget for much fur work on this film, but we quite a bit of it (!) – and of course it was not a problem, but it was just a brilliant way to be able to solve the problem,” notes Breakspear. The ‘fur’ power lines was a solution that also relied on having an accurate 3D layout of the entire set.

Nuke became a central hub for the team, with referenced geometry, and layers of green screen extras, and complex projections. Breakspear is clearly extremely pleased with the pipeline and Nuke as a product. The work that the Method team did pushed Nuke towards its limit, but it never reached Nuke’s limit and all the shots worked out “extremely well. It played a major part, and we embraced (Nuke) as a hub for this type of work. We are not the first company to do this, but this is the new paradigm, this is going to be the way people do compositing. I was saying this the other day, once upon a time you could gather 10 (film) compositors and you could almost have 10 different compositing platforms that they all worked on. You take 10 compositors – take a 100 compositors from a 100 different companies and you’ll find that 90 something of them are Nuke – and I have not seen a time before where that was the case they have the market right now – and deservedly so.”

Buf adds to the effects of Dark Shadows

Buf completed several sequences for the film, under visual effects supervisor Christophe Dupuis. “We originally had to work on non invisible effects as we had a whole sequence with animated paintings,” says Dupuis. “As it sometimes happens the work changed along the road: only one shot with the painting is in the cut and we got invisible effects: a younger Alice Cooper, the mirror ball sequence or cracking glass shot. But that was very exciting knowing that we would have to collaborate with Tim Burton.”

For a scene of Barnabas and Angélique in a love tango, Buf created an extra long tongue and multiple arms ripping Barnabas’ shirt off. “Technically,” recalls Dupuis, “the shirt shot was the most complicated and most challenging shot to complete. The original plate was shot with no trackers at all on the shirt, so the first difficulty was to reproduce in 3D the shirt and its movements. For that we developed some tools: a displacement modelling every 10 frames combined with another tool to help with the interpolation. With this model we were able to recreate the shadows of the multiple arms and add the tears of the witch’s nails.”

Buf cracked the mirror ball through a CG sim. “Tim wanted to have something more spectacular than the real mirror ball that was shot on set,” says Dupuis. “We began with something close to what was originally shot, but to step by step we added some bounce to the simulation to get something more impressive.Another effect accomplished for this section was the high speed Barnabas – we reproduced a CG double for Barnabas to create a enhanced motion blur effect as he moves faster into the room.”

For Alice Cooper, Buf created a precise CG double. “Then we did a second CG puppet for Coooper,” adds Dupuis. “This other one was a younger shape of Alice. We had to imagine how he was in 1972 based on still photographs. We mainly reduced the nose, the hears, the chin and the belly. Another process was applied to the skin to lift it and make it look tighter and younger.”

Finally, for the talking paintings, Buf created some look dev tests to define the characters’ movements along the surface. “Tim Burton wanted to avoid the look of Harry Potter’s animated paintings,” notes Dupuis, “which is more like footage with 2D treatment. The idea was to rebuild in CG the different characters of the paintings. We based their animation on references shot by Angus Bickerton and we enhanced the animations step by step to match what Tim had in mind.”

Pingback: 14 Movie Moments You May Have Never Realized Used CGI | Led Zeppelin Site