Director Terry Gilliam relied on his longstanding relationship with Peerless Camera Company to delve into the hyper-real visual effects for The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus. Visual effects supervisor John Paul Docherty and lead technical director Patrick Ledda talk to fxguide about the film.

The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus

fxg: Peerless obviously has a close relationship with Terry Gilliam. Can you talk about how that helped on Doctor Parnassus?

fxg: Peerless obviously has a close relationship with Terry Gilliam. Can you talk about how that helped on Doctor Parnassus?

Docherty: Peerless was set up about 28 years by Terry and his visual effects supervisor Kent Houston. Peerless has worked on just about every film that Terry has made. It was originally set up to do the animation work for And Now For Something Completely Different, the Monty Python film. Terry’s one of the few shareholders and, as such, the artists have continued working alongside him on a lot of his projects. So normally when he sets up a film we’re very much part of the design process and the creation process.

On Parnassus, at one point there were 800 visual effects shots and I think we ended up with about 640 in the film. Because it’s a very unusual film – it’s not the sort of ILM visual effects treatment – it’s more like Mary Poppins. It’s imaginary stuff and not meant to be real. Each of the imaginarium sequences is built around the style of a painter, artists like Grant Wood.

If you buy into that, and you accept that it’s not meant to be real, then you can see where it’s going. It’s very much a development from Terry’s animations, really. In some cases, we deliberately didn’t put motion blur in there so that we got a stop-frame look that Terry had worked with on other films.

fxg: What were some of the challenges of adopting this approach?

fxg: What were some of the challenges of adopting this approach?

Docherty: It was a big challenge, because it was almost like seven different effects films in one. Each sequence had a different style – once the imaginarium is entered the look is completely different and it ranges from semi-realistic to just completely fantasy or cartoon and back again. As a result, each look had to be developed individually over the course of the show. This meant there was a huge amount of previs work – more than I think I’ve ever done on anything before. Part of it was to get Terry’s ideas into a visually identifiable form. Part of it was that fact that it was seven different styles of movies in one.

fxg: What kind of previs or concept work did you end up carrying out?

fxg: What kind of previs or concept work did you end up carrying out?

Docherty: We did a lot of previs and drawings with production designers, particularly David Warren. We then did previs for pretty much every sequence with a company called Fuzzy Goat, a company at Pinewood Studios in London. Then once we had shot the live action pieces in London, we moved onto a bluescreen shoot in Vancouver, after Heath Ledger’s unfortunate death. We actually then did what we call ‘midvis’. Here we would take every effects shot in the show and bring it to a level where you could see the backgrounds and foregrounds, but not necessarily bring it to a finished shot. It was half-way between previs and the final look.

This was necessary so that we could orchestrate what we were going to shoot on the bluescreens. Otherwise, the actors wouldn’t know what they were meant to be looking at or reacting to. After Heath’s death, it was even more complicated because we had Jude Law, Johnny Depp and Colin Farrell coming in late to the project and having to imagine everything.

So we had to do about 900 shots, at first, as part of pre-edit before we shot the bluescreen. That meant that Patrick and our head of CG, Ditch Doy, had to come up with simple ways of showing what would be very complex effects in the end to get the feeling across so that Terry and Mick Audsley, the editor, could edit it and then we could shoot the bits we needed. Bear in mind, this wasn’t a big Hollywood movie. It’s orders of magnitude less than, say, Pirates of the Caribbean. We just couldn’t afford to shoot stuff that we weren’t going to use.

fxg: How did you tackle the midvis work?

fxg: How did you tackle the midvis work?

Ledda: The biggest challenge was that every sequence was very different. We used different kinds of software for each, too, with XSI, Maya and Houdini. Quite early on we had to assign the different sequences to different software. Another challenge was that Terry wanted to see something very quickly.

Docherty: Yeah, he’d say, ‘I want it now!’

Ledda: And once we got past that stage, I think it was much easier for everyone involved because we knew where we were going.

Docherty: I’ll give you an example. There’s a sequence that isn’t in the movie that Terry put together. It was about 80 visual effects shots. We went to a previs level, then a midvis level and then we shot all the miniatures. It was a gorgeous thing – it involved a child who earlier in the film had wandered by accident into the magic mirror and Doctor Parnassus translates him into the world of imagination. He ends up on a tall rock spire with a choice in one direction of a huge fairy world called ‘War World’. There’s these kids running around shooting each other with machine guns and helicopters on strings flying by.

Docherty: I’ll give you an example. There’s a sequence that isn’t in the movie that Terry put together. It was about 80 visual effects shots. We went to a previs level, then a midvis level and then we shot all the miniatures. It was a gorgeous thing – it involved a child who earlier in the film had wandered by accident into the magic mirror and Doctor Parnassus translates him into the world of imagination. He ends up on a tall rock spire with a choice in one direction of a huge fairy world called ‘War World’. There’s these kids running around shooting each other with machine guns and helicopters on strings flying by.

The look was patterned after Apocalypse Now when they go up the river and it becomes like fairy land. On the other side, there was this beautifully designed building that was very much like a Greek temple with elephants holding the world up and hundreds and hundreds of kids playing piano. It was a bit along the lines of The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T, the Dr. Seuss film. So the child had to make a choice between the two worlds. Visually, this was one of the more impressive sequences in the movie.

But when we got the midvis together, it ended up being too much. It was in the first 15 minutes of the film and it was almost too much, too soon. Terry had to make the very tough decision to pull it, even though we’d gone that far into it. Now, we wouldn’t have been able to make that decision without having done this very extensive previs and midvis. I’m a bit gutted we never finished that sequence because visually it was spectacular, but I think dramatically Terry was right, because it would have ended up leaving the audience completely confused.

fxg: Do you have any other favourite sequences you can take me through?

fxg: Do you have any other favourite sequences you can take me through?

Docherty: I’m particularly taken by the fly-in to the monastery with those huge elephants. That was a large model built by a chap called Leigh Took at Mattes and Miniatures out in the old Hammer studios west of London. When you see that shot, there’s a bunch of scaffolding running up the side of the half finished temple. They were actually mostly coffee stir sticks taken from the local coffee shop! That shot leads to several monks floating on carpets. That’s classic Terry.

The flying carpet bit – no one had ever talked about it – but on the day of the shoot Terry said, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if they were on flying carpets?’. So they got them all wired up and it made for the biggest wire removal I have ever seen in my life! Every carpet had eight wires going up to the ceiling rigged up in a day. But we found the money to clean it up and I think it looks fantastic. They’re all floating in the air, bouncing about. That was a bit of inspiration on the part of Mr Gilliam on the day.

The other sequence that works well for me is the Grant Wood one where Jude Law is walking on the stilts on a ladder that breaks apart. He’s being chased by a Russian gang. A lot of Wood’s paintings have these distinctive trees and Disney-esque landscapes, so Terry latched onto that. The tricky thing about it was that it’s quite difficult to make someone on stilts that are 50 foot high look believable.

We managed to find a physical effects guy in Vancouver who did X-Men 3 to build us a rig which Jude could stand in and walk like he was on stilts. We could then control the width of the stilts at the bottom so that the movement made sense. Because he’s in a cartoon painting world, I think the scene works because his physical movements make sense.

fxg: What were some of the main technical challenges of the imaginarium sequences?

Ledda: In some sequences Terry wanted water to behave more like oil, so we couldn’t just develop one system for the entire show. There’s one sequence with a snake coming out of the water with Johnny Depp in it. All of that was built in Houdini. Terry wanted this black water to form into a snake with Tom Waits’ head. We used a mixture of fluid and particle effects for those shots. In another sequence, Terry decided he wanted this cow to hit a gondola in the water. We had two weeks to build a CG cow with fur in water, which was more like oil, so it would be sticking to the fur. You only see it for 30 frames, but it works. We were trying to convince Terry to swap the cow for a barrel, at one point!

Docherty: The problem is the cow was originally our idea, so Terry said, ‘Well it’s your bloody fault!’

Ledda: Yeah, we had done some concept work in Photoshop with a cow, so eight months later Terry wanted it for real. And there was a lot of other creature work as well – the snake, birds, jellyfish, animated hands, cows. Considering it was a relatively small team and that each sequence required its own pipeline and compositors, it came together really well.

fxg: Can you talk about the hyper-real nature of the effects work?

Docherty: The tricky thing was that Terry has this encyclopedic knowledge of visual arts and painting – and he’s no slouch with the pencil either. He understood the problem, and we understood the problem, that if we started to get too close to realism, to traditional Hollywood effects, he reacted very badly. He said everything we were doing had to look like it came out of somebody’s head. It’s not meant to be a real world – it’s an imaginarium.

It’s actually a difficult thing to do when all the tools you have at your disposal are pointed towards making it look real. Effectively we had to make a stylised version that was more Mary Poppins than Star Wars, but it had to be believable enough not to throw you out of the story, and it had to be visually appealing enough not to make you go, ‘Oh, that’s terrible.’ It’s a very fine line and something that we consciously thought about.

fxg: What was one particular shot where that approach had to be taken?

fxg: What was one particular shot where that approach had to be taken?

Docherty: In one sequence, the entire Vancouver concert hall falls apart around Colin Farrell as his dreams go down. That was a different challenge because it’s not really CG at all – it’s projected bits of buildings flying apart. The line was different on every treatment. If we went too far Terry would say it was too real, and if we didn’t go far enough, people were going to laugh at it and it wouldn’t work. Both from a technical and creative end, particularly from a visual effects point of view, it was a very unusual approach.

Ledda: For that concert hall sequence, Terry originally said to us that it should collapse or break apart. So we built a whole shatter system in Houdini to have cracks go up the walls and have debris coming off it. But eventually Terry said he wanted something more simple, something more graphic.

Docherty: It’s true. He looked at it and said, ‘It looks very clever. It’s very nice. But this guy is going crazy. It needs to be much more graphic.’ Cartoon is not the word I’m looking for, but…

Ledda: …It was almost like a puzzle.

Docherty: Yeah, exactly. The fact that it was graphic made it more evident that it was happening in his brain and not that it was happening in some other dimension. Is that clear?

Docherty: Well it didn’t at the time – it nearly drove us nuts! There’s another sequence where Colin Farrell is sailing in a gondola down a river and it’s very much patterned around Maxfield Parrish, the painter. The thing is, it worked great for stills, but no-one had ever seen a Parrish painting move, so it didn’t work initially. We had to go through an immense number of design iterations to make this moving painting concept work. There was a sequence in What Dreams May Come when Robin Williams basically dove into a living oil painting – a tremendous effect and very influential – but it had that same problem of trying to be fantastical and believable. We had that problem on every sequence!

fxg: Were there other sequences you had to play with like that?

fxg: Were there other sequences you had to play with like that?

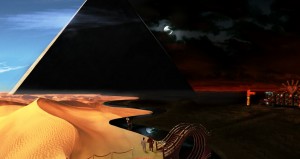

Docherty: In one of Johnny Depp’s scenes, there’s a pyramid in distance with a gondola coming down the river towards him. The foreground was shot live action, it was tracked and then we added in the CG elements. It was built to normal perspective, but then Terry came back and said it wasn’t right, that this was an imaginary world and the perspective should be skewed. So he drew tracings over the layout and we mucked about with it and basically destroyed the perspectives. If you look at the shot, the pyramid is much bigger than it should be, the river is much closer.

It’s very much patterned as a painting and consciously done. It was quite difficult to do, I have to say, but I noticed in a couple of the reviews that they noted the perspective was wrong! I was just shaking my head saying, ‘You really haven’t got it have you? Of course it’s wrong! We started with it right. We spent three months making it wrong!’ Terry always polarises opinion. In the end I think you have to buy into it. It’s very consciously non-real effects. It’s very consciously imagination driven.

Ledda: Yeah, this specific pyramid sequence – half the world is daylight and half the world is night. We spent weeks trying to come up with a transition between the dark red sky and blue sky, but Terry said, ‘No no, just do a straight line.’ It looks very simplistic when you see the result.

Docherty: We did loads of weird defraction effects between nighttime and daytime. Mixing clouds. Shimmers. Then Terry said, ‘This is not about making something look pretty, it’s about a cartoon inside this guy’s head. Let’s just try a straight line.’ And it works. It’s a difficult concept to grasp. Terry was very much about trying to make a visual effects film about visual effects in your head, not in the real world. It leaves a lot for the viewer to think about – not just story-wise and character-wise, but also visually. You have to think about what you’re looking at. Terry’s very consciously made a film where people have to stretch themselves. It’s certainly one of the most unusual things I’ve worked on for a while.