It’s an incredibly strong Oscars race this year, especially in the Best Animated Feature category. The nominees are Brave, Frankenweenie, ParaNorman, The Pirates! Band of Misfits and Wreck-it Ralph – films that span both the worlds of stop motion and computer animation. fxguide talks to two directors representing both – the director of Pirates! Peter Lord and Brave director Mark Andrews.

Peter Lord – The Pirates! Band of Misfits

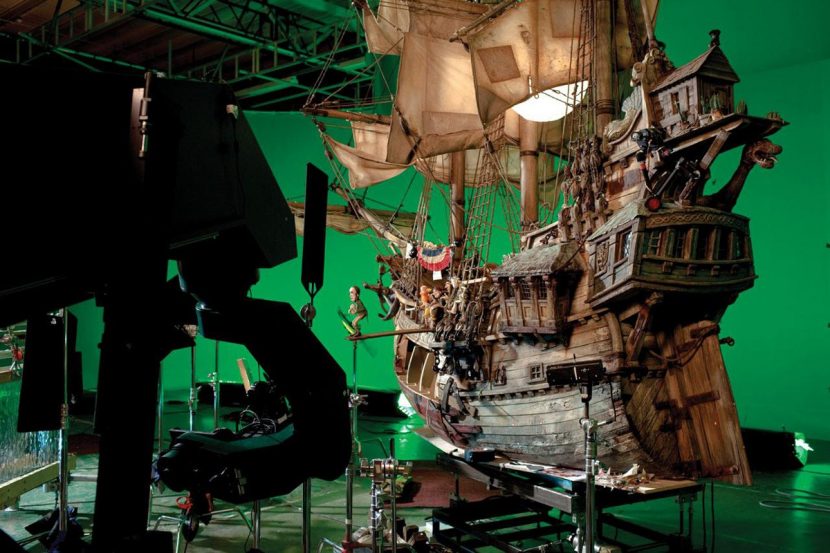

Peter Lord has crafted some of the most memorable stop motion films and characters in recent memory, including Wallace and Gromit and Chicken Run, and his studio Aardman Animation is synonymous with advancing the art of animation. On The Pirates! Band of Misfits, Lord and Aardman embraced both practical and digital means in accomplishing the story of an old-time pirate who just wants to get his mojo back.

fxg: It’s great to see three out of the five nominees are stop motion pictures this year. What is it, do you think, that keeps drawing audiences to stop motion films? They kind of have a magical realism to them, from my point of view.

Lord: Yes, magical realism’s quite a good word for it, actually. It’s very grounded, isn’t it, stop motion? It has some of the rules of the real world about it. There’s a certain solidity of stop motion, I think. This sense that these are real figures with weight and mass living in the world that has weight and mass. That’s just one of the attractions of it – there are many others. It’s part of a bigger thing that the audience understands the reality of this world.

And these days people see the most amazing things in all kinds of movies – animated, live action – the most astonishing images. These are visually very believable but also, unfortunately, emotionally not believable because we know it’s CG. There’s a level at which we as viewers say wow it’s a great set-piece but we don’t believe it. But with stop-frame, funnily enough, even though it’s of course an illusion, it has this grounded feel and the audience kind of thinks yes, that was tangible. If you were there you could have touched that. It could have happened. Which I think is very attractive, personally.

Then in Pirates! I have broken that rule a bit by using some CG. But I feel as if we have an oasis of absolute reality in the movie – a comic reality, tangible reality and around that you have a magical halo of scale and scope which would be difficult in the days of Chicken Run, for example.

– Above: watch a making of featurette on Pirates!.

fxg: You mention the tangibility of the animation and the final film – that’s an attraction for the audience and filmmakers too isn’t it?

Lord: It’s one of the pleasures of puppetry. Now, puppetry is a word covering many artforms, from the Muppets on. One of the joys of puppetry is you know you’re seeing a puppet and the other part of your brain thinks it’s completely alive. That tension there is very attractive to people, I think. Maybe it appeals to something very deep in our psyche. I observe that people generally love puppetry, when it’s done well, when it actually works. Maybe it harks back to something very deep in us, when we all played with a toy as a kid. I can’t explain why it’s there and it seems strange to talk in these terms to adults who are perhaps a long way from those children, but I think it’s a very deep instinct. If you go to some museums you’ll find dolls from Egyptian times so it’s been done for a long time. It’s quite important to us human beings.

Because you can’t keyframe the animation – you have to start at frame one and go the end frame – it has the dynamic of a live performance. You don’t know exactly where you’re going to finish. There’s a level of uncertainty, spontaneity, there’s a healthy level of fear for the performer. Are they going to get it right? They’re surfing that wave of performance and are they going to keep on that wave all that way through? There’s some tension and adrenaline in their bodies. And all of these properties mean the animator is never bored and the work is exciting.

fxg: On Pirates! you were also able to embrace some new technology too, though, shooting on DSLRs, and using CG and compositing?

Lord: I’m very happy with what we achieved. From the digital SLRs through to all the functional things, like cleanup and rig removal, through to the extreme end which is creating some CG characters to go in with the puppets. All those things made it easier for me as a director, and it just freed me. So if I said what I wanted to the production team, there was always this gang of people who said, yeah we can do that. That was a great feeling. On Chicken Run, which of course I am very proud of and love very much, my memory of the shoot is a degree of frustration about what was built and what you could do. You’d have to compromise sometimes about where you’d put the camera. On Pirates! it was great not to have that.

For example, for the pirate island we wanted the camera to fly in like a helicopter from a great distance. We took the camera back (in a big studio, mind you) right back to the studio wall and it wasn’t really far enough. So we took it back a little further in post production and built digitally what was not there. So there’s a combination of beautiful Aardman set and then digital technology that lets me get extra mountains and ships in the foreground. I thought it was a great power to have.

– Above: watch a breakdown of the CG and fluid sim work done for the sea monster in Pirates!.

fxg: I was also thinking one of the big changes was doing something like the CG water simulations for the ocean.

Lord: One of the obvious challenges from the script was how were we going to do the sea. And as you know, it has been done with stop frame in the past. But it would have been a nightmare for us – it wouldn’t have looked real, just more stylized. I needed to know we could have a moving sea with the rises and falls and pitch, so it was obvious we would need to have a heavy wooden boat floating in the sea. But having made that ‘easy’ decision, we spent months getting the sea to look right. There was endless debates about scale, really. One thing we did was, I kind of asked for *less* detail in the water. I know that CG people sometimes love to make the water absolutely believable with all its different depths and layers, reflection and refraction – and we kind of held it back. That was deliberate, of course, so that it didn’t look too real – then we messed around with the scale of the water. How big are the particles when it splashes? We tended to go for bigger, basically, to take away from reality.

We did some test shots where we put a puppet in front a CG sea and the sea was so believable that it just looked as though we had shot some sea and stuff a puppet in front of it. And that was kind of ridiculous because that would be a really cheap thing to do, and not at all believable. So by making it more stylized it seemed to tie in much better. We did one test I remember where we made the sea the same scale as the ship. The ship was approximately one-sixth scale, so we made the sea match that, then it just looked like we’d shot the scene in a tank like a movie from the 50s!

fxg: Apart from the CG capabilities, what do you perceive as the biggest change in stop motion animation and what do you think will keep changing?

Lord: When I used to work, we were always animating blind. So with a roll of film in the camera you wouldn’t know until the reel was processed what you had done. That’s how I started and worked for 10-15 years before we had the first primitive video assist system which was tape based. That way I worked was the same way the absolute master of the art Ray Harryhausen would have worked.

So all the performance on film is only held in the animator’s head – he can’t check it. So these days, or at least for the past 30 years, that’s not been the case because you can always use video assist. Now with digital, every frame the animator does can be checked and see if they’ve got it working, does it follow on in sequence, is the increment right. That is a huge change. Part of me – the old boy – thinks it would be great to go back working in that way but there is earthly reason why anyone should go back. I mean, it was shot fast and it was fantastically inaccurate. It slowed the animators down, which I slightly regret that now, and it perhaps removes some sort of dissipation of energy.

As regards what changes from now on in, it’s hard to see what we’d change. In terms of the way people now animate, I actually don’t want them to have any more help! I don’t want, personally, stop motion to look like CG animation. I mean, on Pirates!, for example, we shot double frame whenever possible – that means that our animation isn’t smooth like computer animation – it’s not meant to be and I don’t want it to be. I want the viewer to perceive that animation and remind the viewer that it is a solid puppet and not a CG construct.

Mark Andrews – Brave

Directors Mark Andrews and Brenda Chapman are nominated for Pixar’s deep and textual Brave, which tells the story of a young Scottish heiress who isn’t like all the other girls. Here, Andrews tells fxguide about how the environments of Brave were realized and how he took a very practical – and artistic – approach to Pixar’s tech prowess.

fxg: How did you flesh out the world of Brave when it’s something you literally have to build from scratch?

Andrews: Well we have to go there. Number one. To understand what exactly it is. I’m Scottish – I’ve been there several times. I already knew how the landscape evoked mystery and evoked magic, and not only a sense of danger but scale and epic-ness and wonder, too. It’s a very appealing dynamic landscape. But I had to go back to look at it again with that idea in mind – what makes it that way so I can translate it. So when I come back to my artists and animators and lighters, not only are they looking at reference, but I can give them a context to that reference.

The funny thing is – we’re storytellers, right? So it all comes back to storytelling. I’m telling them the stories of my travels there, all of our experiences, and they fell in love with those stories – thus, they fell in love with this world by connection. Everybody became very passionate about what they were working on. It had a different context versus some clinical ‘Well, this is some Scottish pine, this is the bracken, this is the angle of the light, 67 degrees off the northern ascension…’ They’re getting a feel for the place and the mood, instead, and they become storytellers themselves.

fxg: So what were some of the things you took away from Scotland that made it into the movie?

Andrews: There were a lot of things. One of the big things was that there is stuff growing on everything. We had moss everywhere. There’s this thing called Spanish moss. There’s something that grows on every surface, whether twisted or eroded by the weather. It makes this this very rounded place with not a lot of sharp lines.

Also, the variation in the light. Lighting comes and goes very fast because of the changing weather – we were out there watercoloring. It was this beautiful pastoral, bright and sunny look that I’m layering in and then all of sudden it starts pissing rain and now it’s all grays, and the color’s been sucked out of it. And as I start on another painting, the clouds are gone and the sun is out! But it’s windy as hell so I can’t keep the painting down. And this is all in the span of ten minutes. It changes very fast. It’s very dynamic.

So we wanted that to all be reflected as well. Not only the change in landscape of the forest from bracken-covered highlands to the running rivers, to the ancient brochs and hillforts to the medieval castles – but also the different colors and how much light or not light there is. It’s a very moist place. There’s atmosphere hanging in the air everywhere, and we don’t do atmosphere in 3D. We just don’t do it, but it exists out there in real like. I basically smoked the set on every shot – I had them put in atmosphere and particulate matter so that we would be shooting through that. It’s also very characteristic of Scotland.

fxg: Can you talk about how you art directed the environment?

Andrews: There was a lot of art direction and concept for the types of trees, the types of rocks, ground covering, the castles, the shapes, the colors – but then when we would compose a shot and light a shot, some of that was a little less production design. We definitely had the light going and it was very theatrical lighting to direct our eyes. But when we put in atmosphere, I just put in the atmosphere – I didn’t tell them where to put it, I said just drop in a cube of atmosphere and we either turn up or turn down the density level and that was that. I also wanted clinging fog to the trees or down on the ground, and we had a very organic approach to it and let it be what it was going to be. Because, you know, out in Scotland, that’s not production-designed. You just get what you get. That kind of organic-ness was a characteristic of Scotland.

fxg: I guess in the same way you could manage something like Merida’s hair to an extent as well.

Andrews: Well, in the computer you have absolute control of how her hair overlaps. I could paint a picture and have it very much designed and controlled in terms of character animation. I remember Brad Bird was doing that a lot on The Incredibles, be very specific about what Violet’s hair would do or what a cape would do. I didn’t come at it that way – all I wanted was that it moved right when she moved. I didn’t say I wanted the hair over her face at this frame or to bounce down here or hang in the air. I would just look at and say, ‘The hair’s not moving right, that doesn’t look like gravity, I think that’s moving too fast or too slow, the curls aren’t moving right, or they’re not getting taught enough.’

I mean, some of our technical artists here have PhD’s in physics. Here I am, I barely made it out of algebra, arguing gravity with them. They would tell me, oh no, that’s gravity. And I would say well that’s gravity in la la computer land but it doesn’t *look* like gravity or *feel* like gravity. And we’d have long discussions about what needs to happen to the hairs. What happens to curly hairs versus wet hairs? How does a horse tail move, versus a horse maine? Once we started getting into those parameters, then we had a basis to identify if it was right, or not right. And that’s as far as my direction went. When it was right I just said, Final!, next shot, and we moved on.

fxg: And the same with things like water sims?

Andrews: It’s hard enough to get a computer to make a curved line, and make something look not plastic, so why do I want to put my crew through any more hell by art directing the water to behave a certain way. Like saying, ‘No, I don’t want that splash, I want this splash!’. It’s a splash, move on. I mean, they would ask me, because some directors do get into designing particular effects or sim elements. They would ask me, ‘Well, what direction, how high, how big, droplets?’ and I would say, ‘I don’t know, run the sim, let’s see it.’ And I’d say, ‘That’s fine, move on.’ And they’re all, ‘Woohoo!’

I like that serendipity. That was kind of my philosophy, especially in this film – the serendipity that you get in say a live action film which I’ve also had the pleasure of doing – you just get it. A hair blows in your face, somebody yells ‘Cut! Cut!’ and I’m like ‘Why are you cutting?’ and they say ‘Well it’s covering the actor’s face.’ And my response is ‘Well, it’s windy, of course it’s covering the actor’s face – we could have used that take.’

In animation you don’t get any accidents like that. You don’t get any of the dirtiness or grittiness that comes with this reality – these surprises that can make your shot. So if ever something happened, if a sim went wonky and her hair dropped down on her face or got stuck on her clothes, I would say that’s great because that’s what curly hair does. It’s covering the eye – leave it! Or if a splash went too high, I’d want to leave it. Or if a camera fell out of focus, or there’s a little jiggle in the camera move – they would want to clean it up. And I would say, ‘No! Are you kidding me? Do you know how long it would take to get that mistake if we wanted to do it on purpose? Leave it. That makes it organic.’ Film and visual storytelling is organic.