Spy Kids: All the Time in the World is director Robert Rodriguez’s fourth adventure in the franchise, and follows retired spy Marissa Wilson (Jessica Alba) who is called back into action to defeat the evil Timekeeper. We speak to Hybride about their more than 1000 visual effects shots, including their use of ICE to create a whole city.

The film was shot on the ARRI ALEXA and went through a stereo post-conversion process by Speedshape. As has been the case on a number of Spy Kids and other Rodriguez projects, the director’s internal Troublemaker Digital delivered significant design, on-set supervision, previs, post-vis and final shots.

Perhaps almost unashamedly, All the Time in World takes full advantage of its stereo nature and delivers several 3D gimmicks. In fact, the film was marketed as a ‘4D’ release, complete with an ‘Aroma-Scope’ hand-out card for audiences to experience key smells at key times during the movie.

Since the film was post-converted, this also involved the delivery of more than 5000 elements for Hybride. The studio benefited, however from sharing a number of models with Troublemaker Digital and coming up with streamlined techniques for realizing the effects.

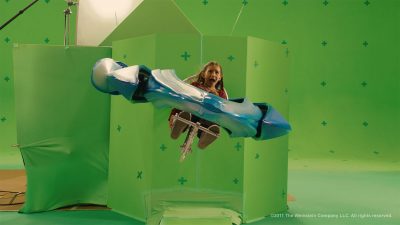

One such technique, used to create the city environment that the kids fly through in their Jet-Luges, enabled buildings and all manner of other details to be generated procedurally. That particular sequence began with a greenscreen shoot at Troublemaker Studios in Austin, Texas, with the effects supervision co-ordinated by Troublemaker Digital.

“We have worked so closely with Robert before,” notes Hybride visual effects producer Daniel Leduc, “that we know each other so well, which means we didn’t need to be on set. Troublemaker took care of everything in terms of the greenscreen shoot and the animatics.”

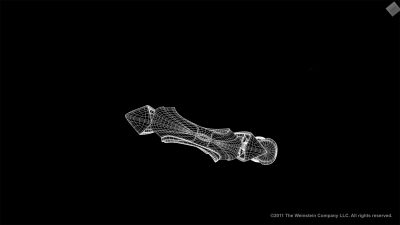

The actors were filmed with minimal props, some kept for the final shots and others replicated in CG by Hybride. “When we started to put the jets in the city,” explains visual effects supervisor Philippe Theroux, “we also needed to put the reflections of the buildings on the paint of the ships, because it was hard to feel the speed of the crafts without it. So we had to do a very close match-move with a CG object in order to create the reflections and differences in shading, and would often replace it with a full CG one where that was easier.”

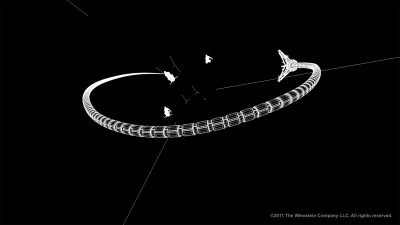

As initially designed, the jets were to fly over the city, but Rodriguez pushed for the sequence to head more and more into the metropolis. “Robert kept suggesting maybe we could fly a little bit lower,” says Theroux, “and then he’d say, ‘Maybe we could go right down to the street level!’. So of course we had to add so much more detail.”

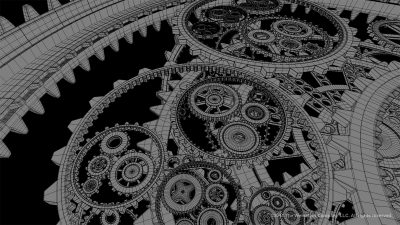

– From above left: greenscreen plate, CG wireframes and the final shot.

For that, Hybride relied on ICE inside Softimage to generate the buildings, traffic, people, vegetation, street signs using procedural scripts. “It was basically a city generator tool,” says Theroux. “You could simply draw the outline of a street, or you could go into google and take the outline of an existing city and then just paint the tree that you like, or choose a lamp post or mailbox for the sidewalk. You can take a street and make it wider into a highway or whatever you need with sliders.”

“We also created a way to generate buildings automatically,” adds Theroux. “We just had to select a neighborhood, and then decide on say ten buildings, then you can pick up any building and change the style, like a glass or brick building. You drag the corner of a building and scale it up and make it wider or taller. It also let us add all the little details like antennas and signs on the road very quickly to make it come alive.”

The studio plans on using the tool for future projects, since it was also one that remained fast for iterations and at render time. “It allowed us to generate a very good looking city, but the geo was not very heavy and the artists had the freedom to create what they needed and change things very quickly,” says Theroux. “We did invest a lot of time early on, but we plan to use it again for future projects.”

The studio plans on using the tool for future projects, since it was also one that remained fast for iterations and at render time. “It allowed us to generate a very good looking city, but the geo was not very heavy and the artists had the freedom to create what they needed and change things very quickly,” says Theroux. “We did invest a lot of time early on, but we plan to use it again for future projects.”

In addition, the film called on Hybride to create effects for the Timekeeper’s Lair, a myriad of time-related environments such as the ‘Armageddon Chamber’, a computer room, an hourglass, the vault and human clock. Other effects included spy gadgets, jet packs, ‘hammer hands’, a lasso, holographic screens, sonic battering ram, among many more. A scene with a spinning needle threatening the kids was challenging, in particular, in ensuring the actors’ feet stuck to the computer generated elements.

That scene also featured Argonaut, a talking robot dog (voiced by Ricky Gervais). A real canine was filmed on set and made to talk and perform spy-like stunts via visual effects. “Robert didn’t want to make him look like a real life animal talking, he had to look like a robot,” says Theroux. “So we animated a slapping lower jaw to be very mechanical. But we still had to track the head of the dog, replace the face with a CG face with fur and track that on top of the real dog.”

Ultimately, Hybride completed 1,114 shots for the All the Time in World – in not much time. The studio had six months from January to July this year, relying on a crew of 95 to deliver 64 minutes of screen time and what turned out to be the most number of shots for a single project ever produced by the company.

Ultimately, Hybride completed 1,114 shots for the All the Time in World – in not much time. The studio had six months from January to July this year, relying on a crew of 95 to deliver 64 minutes of screen time and what turned out to be the most number of shots for a single project ever produced by the company.

All images copyright © 2011 The Weinstein Company LLC. Courtesy of Hybride. All rights reserved.