The 2024 edition of the DigiPro conference was held the Saturday before the start of Siggraph in Denver. In the opening remarks, conference co-chair Kelsey Hurley (Eva Abramycheva served as the other co-chair) noted that this was the first DigiPro outside of production hotbeds Los Angeles or Vancouver and they weren’t fully sure what to expect. However, they were pleased that both paper submissions as well as attendance met or exceeded their expectations.

This event has always been a favorite of ours here at fxguide, with a solid mix of technical papers presented over the course of the day. It’s a great way to stretch ones brain cells and start the week learning about interesting work being done in the industry. Per Christensen and Lee Kerley served as program chairs and lead the selection process for the work that was presented at the conference.

In addition to the presentations, the great thing about DigiPro is the time provided to network with ones peers. They’ve intentionally built in breaks that are a bit longer than you might find at other conferences, along with a 90-minute lunch and a closing reception. After experiencing remote-only conferences in the aftermath of COVID, the opportunity to catch up with colleagues in person provides a reminder of how valuable in-person gatherings like DigiPro are. The networking aspect is really a highlight of the day.

The conference was effectively divided into four sections:

- Pipeline and tools

- Rendering and painting

- Keynote

- Rigging and deformation

What follows is a brief recap of the sections as well as links to the various papers that were presented. The papers can be viewed online or downloaded as PDF files. If you attended SIGGRAPH and missed the DigiPro conference this year, this overview should show why you’d want to reserve a spot at next year’s conference.

Pipeline and Tools

Ryan Bottriell (Industrial Light & Magic) and J Robert Ray (Sony Pictures Imageworks) presented the first session of the day, SPFS and SPK: Tools for Studio Software Deployment and Runtime Environment Management. The paper covers tools that help manage the complexity of developing and deploying software in a facility.

SPFS (Software Platform File System) allows them to build and install an entire software runtime environment into a designated SPFS directory, capture it, and then reproduce that environment on any machine in the studio. Think of it as taking aspects of managing things via git and running it in containers. Unlike a “normal” container, SPFS is not fully in isolation and other files on the host, user information, hardware, devices, and operating system remain accessible for the user.

SPK effectively serves as a package manager for SPFS, allowing easy deployment of software across a facility.

You can download the SPFS/SPK paper here.

The next session, Building a Scalable Animation Production Reporting Framework at Netflix, covered how Netflix enhanced its animation production reporting.

Because of the sheer volume of productions being completed around the world, it was important to make sure that the reporting could be integrated into various studio workflows. Previously, the process to analyze various studio data was incredibly time consuming due to the variety of data types that were being provided. This process was also understandably prone to errors due to the lack of lack of data consistency.

Netflix standardized the data model and utilized Autodesk Flow (formerly ShotGrid/Shotgun) as well as apache.org’s Spark data engine. One of the key aspects is the work in translating a specific vendor’s data in Flow into the data model which Netflix has created (as well as verifying/rejecting incorrect data). The system has been in production for about two years now and is being adopted by more and more studios working with Netflix.

You can download the Netflix paper here.

Up next was Jonathan Penner, who presented the paper Multithreading USD and Qt: Adding Concurrency to Filament. Filament is Animal Logic’s proprietary USD node-based lighting tool. Written in Python and Qt, the app was updated to parallelize processing .

Filmaent’s outliner, which provides a hierarchy of the stage, was a particular point of the bottleneck. the slow performance was primarily due to updating the C++ scene index on a single thread.

The concurrency that the team at Animal added, keeps the UI responsive and makes processing faster. For instance when an artist updates an attribute in the scene (such as color) or if an object or objects in the scene changes. It was important to update the code so that updates can be done in parallel vs. linear. In the end, with the work that is outlined in the paper, the speedup was around 2x.

View or download the Filament paper here.

Animal Logic’s Jon-Patrick Collins followed up with Nucleus: A Design System for Animation and VFX Applications, which is used in many of the facility’s apps such as Filament, FilmStudio, and Forge. When the company transitioned from Windows to Linux in 2010, they standardized on Qt for UI elements. As an example of benefits, they wanted to have consistency in the look and feel of their apps so they adopted a shared Qt stylesheet (QSS). Collins pointed out this would allow them to have easy consistency of say highlight color (blue) across products yet be able to override it for specific plugins (for instance, using yellow in Nuke where this is a main color).

In 2018, they started the next phase of development with the launch of the Nucleus Design System which, as the paper states, “reimagines applications using a plugin-based architecture with application-level configuration replacing application-level code.” This can be used in both standalone applications (such as Filament) as well as applications which run in DCC apps (like Animal Logic’s Forge).

The published paper has a lot of key takeaways, but an interesting aspect is that they now treat embedded mode as the standard case, and treat standalone and hosted modes as special cases in which the embedding target is simply a QMainWindow of our own creation. This is a flip of the previous situation and has been valuable in developing applications for Nuke, Houdini, USDView and more.

Check out the full paper here for more details.

Rendering and Painting

The second section of papers started off with Spear: Across the Streaming Multiprocessors: Porting a Production Renderer to the GPU, presented by Clifford Stein from Sony Pictures Imageworks. It covered the complexity of porting the Sony Pictures Imageworks version of Arnold (Spear) to the GPU using NVIDIA’s OptiX ray tracing toolkit.

The initial target for the port were lookdev artists due to the less-complex setups and smaller environments they use compared to lighters. The aim was to improve efficiency and speed so that they could get faster feedback — something they saw when using Arnold’s GPU implementation.

They decided to add GPU support to their existing renderer, rather than adding a completely separate tool because, according to the paper, “we felt it gave us the greatest chance of success in matching the look of the CPU renderer since artists are very sensitive to changes in looks.”

Read about the process and the benefits in the full paper hosted at the ACM digital library. As to performance, the port provides a speed up of 4x to 6x using the RTX6000 Ada generation NVIDIA cards vs. their CPU workflow.

Continuing on with the rendering theme, Yining Karl Li gave a talk on Cache Points, the system used by Disney’s Hyperion Renderer to efficiently importance sample direct illumination in scenes.

With the number of years that Hyperion Renderer has been used in production, Li mentions that they’re opening up a bit more about the renderer’s underpinnings. The paper this year contains a lot more details than has been available in the past and can be viewed or downloaded here.

About five years ago they spun up development again after they realized cache points could be used for volumetric scattering. Many of their projects had large cloud environments (like Frozen) as well as emissive volume effects so it made sense to try to speed up workflow. The paper this year expands upon Li’s paper from SIGGRAPH 2021

Interestingly, they’ve only had one major instance where they had to disable cache points on effects and this was for a series of shots for Strange World where they had lighting artifacts.

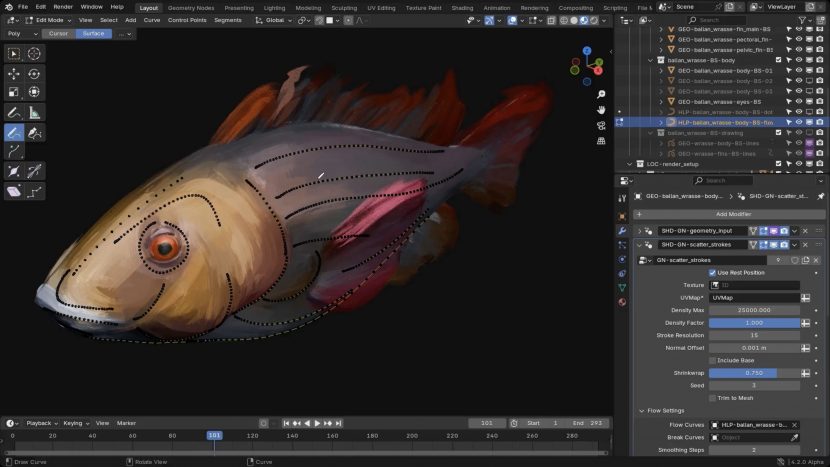

Rounding out the section was Blender Studio’s Francesco Siddi, who presented the paper. He covered how they developed an oil-painting-inspired rendering style, using Blender’s generative geometry and simulation framework Geometry Nodes.

The end result is not an application of texture or strokes onto a flat surface, but utilizes the model to paint along the surface. The process takes 2D brush strokes and then utilizes them in the 3D procedural environment. First, a library of digital scanned brushstrokes and profiles is created. These 2D assets are then used to represent the brushstrokes as three dimensional curve-guided procedurally generated geometry and uses BSDF shading.

This was used on Blender Studio’s Project Gold as a production test case. Read more about the process in the paper in the ACM Digital Library.

Keynote: LAIKA’S Journey in Hybrid Filmmaking

CG Supervisor Eric Wachtman and Compositing Supervisor Michael Cordova from LAIKA kicked off the afternoon sessions with a look at LAIKA’s production over the years.

They discussed how various aspects of technology changed over the years, including the cameras they used to film their stop motion based films. Back in 2005 they used Redlake cameras with direct viewing and playback used an in-house application. One issue with these cameras were that the sensors varied quite a bit between the cameras so they couldn’t easily be interchangeable. After Coraline, they moved to Canon 5DMKII cameras and now they are using Canon R6 cameras.

The films are released in stereo, so they did examine alternate rigs such as RED cameras in parallel or with a beam splitter. However, due to the nature of stop-motion and the subject not moving, they settled on using a motion control rig which can shoot a frame for one eye, shift the camera a specified distance, and then shoot a frame for the other eye, and then return to the original position. They would also do additional frames for passes needed for vfx, such as green screen, backlit, or even UV-style passes. For Coraline, they had 17 motion control systems installed. On the current production, Wildwood, they have over 70 moco systems in place in production.

They also covered LAIKA’s development of their rapid prototyping process which garnered a 2015|2016 Science & Technology Academy Award. Starting with Coraline, facial pieces were 3D printed fusing a white plastic resin which were then hand painted ( there were over 207,000 possible expression combinations). With ParaNorman (2012) and The Box Trolls (2014), they utilized powder 3D printers where liquid glue is sprayed onto powder.

For the release of Kubo and the Two Strings they started using plastic resin printers on the Monkey and Beetle characters. Kubo also saw the first all-printed character, the Moonbeast. The Kubo character has 11,007 unique mouth expressions and 4,429 brow expressions, allowing for over 48 million possible facial expressions. Between the various Kubo puppets used on set, there were over 23,000 RP-printed faces.

You can read more about the RP process in our article here on fxguide.

Rigging and deformation

The first paper in the final session was Developing a Curve Rigging Toolset: a Case Study in Adapting to Production Changes, presented by Animal Logic’s Thomas Stevenson and Valerie Bernard.

The presentation provided insights into the development process at Animal Logic, taking into account real-world situations including adapting to changes along the way. Early in 2023, an animated feature was starting production later in the year and would include a character with a long articulated tail. The rigging team asked for a variable FK (Forward Kinematics) node to simplify existing trunk and tail setups.

For the full story behind the development, check out the full paper in the ACM Digital Library.

Ben Kwa and Stuart Bryson presented Premo: Overrides Data Model. The paper covers development aspects of DreamWorks’ SciTech Award winning animation application, Premo. Recently, the application introduced workflows where artists could use visual programming to build character rigs by assembling pre-authored modules together. This allows the artists to focus less on the technical details and more on the task at hand and the craft.

However, overrides of the modules are critical and this paper focuses on how this is accomplished. For instance, a generic biped template would be used for various characters, but overrides based on sizes or proportions would be necessary. In addition to various properties being different, other things might need to be changed. For instance, they discussed how a character like Hiccup from How to Train Your Dragon would have to be modified — such as when his left leg instance had to be replaced with a peg leg instance.

For the full details on how this is all implemented as well as future work they anticipate, check out the paper at the ACM Digital Library.

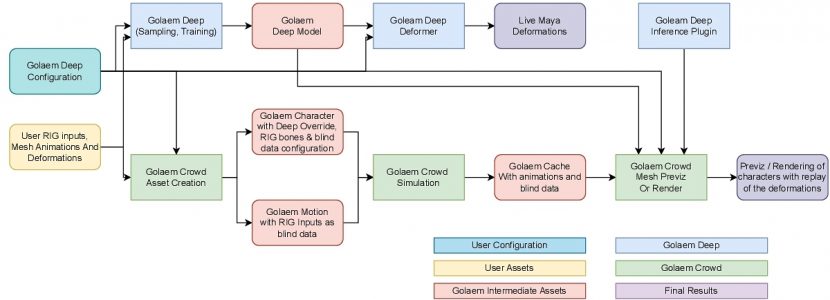

The last presentation of the day was from Nicolas Chaverou from Golaem and titled Implementing a Machine Learning Deformer for CG Crowds: Our Journey. It was an overview of their process of looking at adding deform tools to Golaem, which has become necessary as crowds are used in more projects and has been a big request from customers. They ended up focusing on using machine learning to accomplish the task versus working to reverse engineer deform nodes in packages like Maya and Houdini. This was launched in beta form with the release of Golaem 9 in May, after spending several years in development.

After some initial research examining various approaches, they settled on the method proposed by Song et al. (2020) which can be used to learn both facial and body deformations from both rig controllers and/or a skeleton. From testing the team did, it also provided more reliable body deformation than other methods they tested.

The performance of their result didn’t match the 5 to 10 times speedup in evaluation speed as mentioned in the Song et al. paper (or the Bailey et al. paper the team also referenced). The Golaem team initially achieved a 1.2x to 2x speed up with production assets and determined that the research paper rigs were likely optimized for their model and those factors did not include the rig evaluation itself. Since this 2x speedup wasn’t enough for a new standalone product, they decided to integrate it as a ML deform node in Golaem crowd.

For the required training data, the app supports keyframe animation and they suggest approximately 40 seconds of animation. The training is completed using Thorch C++ (and CUDA if available). As far as performance, the paper states that for “a character rig composed of 266 inputs, 6840 vertices, and a 136 subspace network, the training takes 60min for 5000 epochs on a NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 GPU. Once trained, the ML deformer is applied to the linear mesh and can be used as an animation proxy.”

As a side note, for the presentation at DigiPro, Chaverou wove the story of the development with the humorous thread of creating a killer app and selling out and retiring. With the news after SIGGRAPH that Autodesk had acquired the IP and Golaem, it turns out that maybe there was a little bit truth to the story — though at this point the Golaem team is still fully working on the product moving forward.

Download the paper from the ACM Digital Library.