Another fantastic day has passed at FMX 2011 in Stuttgart. Day three presented perhaps a greater focus on the global nature of the visual effects industry, with presentations by many studios from around the world and some of the key players. Here’s a look at our thoughts on today’s proceedings, plus an interview with conference participants Tim Alexander and Patrick Cohen from ILM on Rango.

The state of visual effects

Former ILM and Digital Domain CEO Scott Ross started the day with a frank discussion about the visual effects industry. He noted the amazing individuals and companies that were pioneers in the field, such as ILM, Doug Trumbull, Apogee, Boss Films and Robert Abel, but then also listed the companies which have more recently gone out of business, despite doing great work and despite the top 20 grossing films of all time being mostly visual effects or animation tentpoles. Ross’ view is that effects companies may need to follow the lead of Pixar, Blue Sky and PDI/Dreamworks in creating content and adopt the outsourcing model to places like India and China with more open arms.

Additional talks and panel discussions took place today on the global production of visual effects – from the U.S. to Europe and Asia. An interesting and honest account of the move towards production in India was given by Philippe Gluckman, Creative Director, DreamWorks Dedicated Unit, Technicolor India who not only talked about what has been set up there, but also showed some great material being produced from Madagascar and Shrek-related content. The goal for the Indian venture, according to Gluckman, was to be as artistically and technically competent as the Dreamworks Animation group in the U.S. and to participate seamlessly in Dreamworks animated films.

Other highlights from Day Three

Weta Digital’s Chief Technology Officer Sebastian Sylwan gave a talk on the Universal Studios King Kong 360 ride. Ron Frankel from Proof discussed the notion of stereo previs, something his company has done for the new Spider-Man film, while Sony Pictures Stereoscopic Supervisor Grant Anderson provided a case study of The Green Hornet stereo conversion process. Also, The Foundry presented some popular workshops on Mari, Nuke, Katana and on stereo.

ILM and Rango

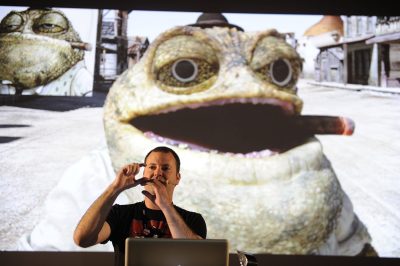

On day two, ILM had wowed the crowds with a killer presentation on the animated feature Rango. Today we got a chance to sit down with ILM visual effects supervisor Tim Alexander and ILM Singapore CG supervisor Patrick Cohen to discuss the Gore Verbinski film.

fxg: Tim, obviously you’ve had a lot of experience on feature films as a visual effects supervisor – is the role of a VFX supe on an animated feature that different?

Alexander: It’s not that different, I would say. It’s a much larger scale – there’s just a lot more going on. It was really the largest film I’ve worked on, with about 1500 shots. I actually found that our department leads were so important in the process. So, Layout, for example, did pretty much operate as its own department and I wouldn’t involve myself too much in there mainly because Gore was so involved with the cameras.

fxg: What about the pipeline at ILM – did you need to change anything in particular to enable the film to go through?

Alexander: We didn’t actually make any structural changes to the pipeline itself. We basically plugged holes! As we started to put through so many characters and assets and tried to get them to render, we found a lot of leaks in the system. For example, we had quite a few issues with asset management in terms of reliably getting information from layout, animation, sim and packaging that up and getting it to the lighting TDs. Jason Smith at ILM was one of the persons making that possible.

There was probably more of an attitude shift than a technical shift, where we really wanted to draw a line in the sand and say this is the front end and this is the back end, and we’re not going to pass anything off to the lighting TDs until it’s been finaled by Gore. So we’d have final cameras, final animation, set dressing – we wanted to have final sim but ended up working that out later. We wanted everything done before we passed it to the lighters. That’s atypical of our visual effects movies as usually production schedules are so tight we tend to work in parallel with all those departments.

fxg: I really felt like Rango had a photographic feel, not necessarily a photorealistic feel, but that it comes through in the character design and the camera angles and framing. Can you talk about how that affected your work on the film?

Cohen: A lot of it was going back to the original reference. We saw clips of There Will Be Blood which was referenced a lot. We’d continually look to certain frames and looks and going back to the reference. It gave us a clear mark to hit and a real reference. And then when they were developing the characters, it was Crash [McCreery’s] artwork.

Alexander: The other references were Leone movies, things like weird faces that were very asymmetrical and organic. I think there was a common language – Gore had come from live action – so it was really the way we knew how to speak about making the film, and I think that bleeds through into everything. Gore of course got the whole cast on stage and acted out the movie, because it was foreign to him to have had them acting in a little booth. It was always this kind of live action mentality going through. Having a DP (Roger Deakins) as a consultant, and just every point of the way referencing back to live action movies.

Every time we did an effect, too, we’d look at how that might happen in real life and then try to emulate that. Like you said, we weren’t going for photorealistic – no one was going to believe animals were real anyway! – but it was also taking a basis in reality.

fxg: Were there pieces of tech that helped you with that – I’ve seen a video for example of a hand held monitor that let you see a real time view of the town.

Alexander: We called that mo-cam, which was a way that we motion captured a camera. We had a tablet, but you can also look through a camera. We programmed the buttons on the tablet to be like a lens kit, so Gore could switch between lenses – from say a 27 to a 35 to a 50mm. Through that he was seeing a virtual world, so he could walk around our motion capture stage and it would capture the camera in real time and render the sets in real time for him to look at. One of the interesting things we found, Gore was very concerned about whether the space was big enough. So when we built the saloon, he had to know for sure what the space was. He’d say, ‘I know if I have a 27mm and it was 30 feet it would be about the right size.’ So that’s why we had him use the stage to give a much better sense of the spaces.

Cohen: It also means he didn’t do any impossible camera moves, that could never really be done on set. It was shot as if we had gone to the town and been there.

fxg: I think the other thing about the photographic look is that it’s quite dirty – what were some of the tools or techniques that made that possible?

Alexander: Well dirt was basically the theme of the movie – ‘cheap as dirt’ was the code name for the film and Dirt was the name of the town. I really think a lot of the initial look came from Crash’s artwork, and then our modelers worked really hard with Crash and Gore pushing on our team to make things imperfect. There could never be a straight line on anything. All the models had to be asymmetric, which takes more time in modeling. If you look at Rango, his head’s a huge trapezoid – there’s nothing symmetrical about that. The hair sculpting was also a big part of it – anything we could do to make it greasier and stuck together was important.

fxg: What kind of effects work and tools did ILM need to develop further for things like water and fire?

Cohen: Well, ILM has done all of those effects before in live action movies – all those things were there but they needed to be doing them efficiently, say for the big water sequence at the end. I think it was more the scale. And we were putting dust into every shot, rather than just a few.

Alexander: We did have to work on glass, say for when Rango is stuck in the bottle. We use RenderMan, which is not a raytracer and doesn’t deal great with refraction. We had guys working on our shaders to get them to be more efficient and trying to render frames in less than 24 hours. The other thing we used a lot of was fluid sim Plume, which is GPU-accelerated. We generated a lot of dust with it. It helped us with the wide shots of the birds running and the huge dust clouds coming off of them.

Cohen: We also had a dust template set up so that the town came with a dust pass that the lighters could use it and control it.

fxg: Did your compositing follow a traditional visual effects approach?

Alexander: We went into the show thinking we weren’t going to use that much compositing, which was funny because I come from a compositing background. It turned out we really needed to rely heavily on compositing to put those final touches on the shots to help with the dirty and gritty feel, lens flares, flaring of the sky, eye grads, vignettes and depth of field. A lot of things were already in our bag of tricks. Nelson Sepulveda was our comp supervisor and he really pushed for multi-channel EXRs, where instead of having all of our AOVs broken out into different read nodes, he wanted them combined into one EXR file. So there was one read node and we had tools for being able to read in and out diffuse spec or scatter for instance. It made the comp scripts really tight.

The other thing we did a lot of work on was depth of field, because obviously there’s a lot of problems with occlusion in depth of field. Our typical approach is to break it out into many passes and blur each of those out separately which we still do, but we also did a lot of work in being able to better calculate occlusion in depth of field.

Cohen: And because ILM had those talented compositors there, that meant we could put that into the animated film. Not all animated features have those experienced compositors and so often they don’t have that real world feel.

Alexander: One of the benefits we noticed was that all the improvements we made to our pipeline for Rango dropped back into our visual effects work for other films. It wasn’t as if we separated the pipelines.

fxg: I think one of the more interesting things about Rango also was that it was completed both in San Francisco and Singapore. Can you talk a little about that actually worked from a pipeline and practical point of view?

Cohen: In Singapore we did 25 per cent of the film. We covered almost all of the departments – animation, lighting, effects, compositing and cloth and hair. The long schedule allowed us to stretch things out in a good way, in that we never worked a weekend in Singapore and we took the amount of work we were capable of. We worked on it for over a year in Singapore.

We would mirror all the data between locations. The way we run it is that we only have a two hour overlap each day, so we had daily cineSyncs so we show the work to Tim and he would send us notes. Even though it only gives us that two hour overlap, it does gives us a 24 hour work cycle. It was one of the big advantages on Rango, in that if we had a problem during the day, we could send the file over to Tim and his team and they could work on it.

Alexander: The other thing we did was send people over to Singapore to help troubleshoot, because there were a lot of technical render issues on the show, so we put some people down on the ground with Patrick to help with the show.

Cohen: There was a lot of back and forth, where we would send over our leads first to train in San Francisco. I also worked there for eight weeks before coming to Singapore, so it was great training ground. I think 70 per cent of our team had no feature film experience, but they were really mentored for the whole process with training and it just turned out to be a fantastic way to get a junior team up and running.

Alexander: It really worked out well – from my point of view, I would come in in the morning and there would be 15 to 45 review requests from Singapore and those files were already copied over so I could look at them live. We would do art notes in the morning and get on the phone in the afternoon and hand over the notes. So we would have the time to look at things and think about it.

_______________

We finished the day with some drinks and a reception with The Foundry. On the final day I’m looking forward to the Harry Potter tribute which will bring together a number of VFX practitioners who have worked on the series, Pixar’s Saschka Unseld and his talk on cinematography and staging in Toy Story 3 and Cars 2, and a presentation by Pixomondo on Sucker Punch and Hindenburg.

Thanks to FMX and Reiner Pfisterer for the FMX photographs in this post.