fxguide is now in Vancouver for SIGGRAPH 2014. Here’s a look at the opening sessions from DigiPro and also Day 1 of the SIGGRAPH conference.

DigiPro 2014

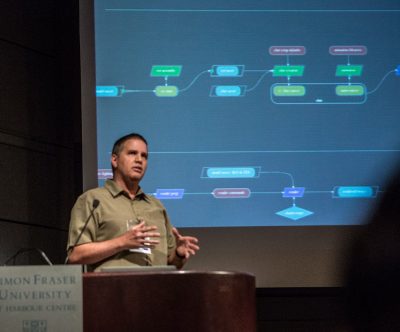

Right before SIGGRAPH began was the DigiPro symposium, an all day conference of CG and visual effects professionals and academics presenting on a range of topics. Started just two years ago, this year was a sell-out – more than 200 people heard from their peers on subjects such as modeling tools, CG pipelines and effects tools.

DD’s Doug Roble also gave a fascinating keynote on the Sci-Tech Awards process. DigiPro is also more than just the presentations, since it also gives a chance for professionals to catch up with fellow industry professionals from around the world.

Keynote by Doug Roble, Creative Director of Software at Digital Domain

Digital Domain’s Doug Roble provided an insight into the relatively ‘secret’ Sci-Tech awards process, from submission to consideration by the awards committees. It was literally, says Roble, the first time there had been a talk about the Sci-Techs Awards like this.

Roble began by outlining the three classes of Sci-Tech awards:

1. Tech Achievement Award – a certificate where there has been technical innovation, impact on the way films are made and impact on the industry itself.

2. Scientific and Engineering Award – a plaque where that innovation and impact is advanced.

3. Academy Award of Merit – an Oscar statute that reflects extreme innovation and impact. This level of award is rare.

Interestingly, Roble noted that unlike the main Oscars awards, the Sci-Tech Awards were not a competition. There are no nominees – people turn up to the Awards event knowing they are winners (in contrast the room at the main Oscars progressively fills up with losers, joked Roble). The effect of this, also, is that the Academy recognizes innovation that may be occurring across inventions by different people that may have taken place around the same time. That’s why they investigate innovations in much detail prior to handing out awards.

Roble’s own research had unearthed 782 Sci-Tech awards since 1930s (with often multiple people are listed on each award so of course). In the 1930s most awards were for sound and then in the next three decades moved towards film stock, cameras, projectors and film equipment. Ub Iwerks received a Technical Achievement Award for the design of an improved optical printer for special effects and matte shots in 1960. Then in 1970s and 80s things like high speed cameras, the Dykstraflex, bluescreen tech and computerized systems began receiving awards.

The 90s, of course, saw the rise of computer software awards. Disney’s CAPS was the first recipient – it included 13 individuals on the award. Other winners related to morphing, digital scanning and compositing. The rise in software led to the forming of a SciTech Digital Imaging Technology subcommittee. In recent times the rise in digital cameras and projectors has also led to the creation of the Digital Apparatis Technology Subcommittee.

Perhaps the most insightful part of Roble’s talk was the outlining of the steps to an award:

1. Create an innovation – he says the closer an innovation is to creating an image, the easier to get an award. For example, render queue software was a recipient of a Sci-Tech but it was initially challenging for the Academy to see how such a technology played a part in bringing film images to the screen.

2. Wait – the Committee needs to see that the innovation has an impact, which won’t necessarily happen as soon as it is used in a film. However, potential submitters should look out for press releases from the Academy about possible awards because part of the process involves submissions on other similar technologies.

3. Submissions – submitters need to answer 29 questions covering the history of their innovation, how it was created, the cleverness, who is behind it, etc.

4. Decide what to investigate – the Committee will determine what to look at each year. One reason it might reject an innovation is that the field is not ready.

5. Similar technologies – as noted above, this is the chance for submitters and the Committee to investigate similar tech. And it has to be very similar. When deep compositing received a Sci-Tech award, the investigation was restricted to deep techniques only and not compositing in general.

6. Surrogate groups formed – this is how the committees are organized

7. Demo night – the submitters have 6 minutes to show off their innovation to the Committee and to the other awardees under consideration. “It’s like Tech Papers Fast Forward on acid,” says Roble.

8. Investigation – this process takes 2 months and the Committee must try and look at all similar technologies (even if no further submissions have been made). Awards are generally restricted to 4 names only.

9. Checks and balances – the notes and decisions of the Committee go to the Academy for vetting.

10. Announcements made

11. Awards night – as noted, only the winners attend.

Currently, Richard Edlund is the Sci-Tech Chair, and there are between 40 and 45 people in the Awards committee made up of reps in the fields of cameras, lenses, grips, VFX, sound and other areas. The Academy does not publish the names of committee members (although they are not sworn to secrecy about their membership). Roble says, however, the idea behind not publishing the list is so that no-one can adversely impact the consideration of an award.

Delta Mush: Smoothing Deformations While Preserving Detail

We recently spoke to Rhythm & Hues about their Voodoo toolset – this talk from Joe Mancewicz and Matt L. Derksen specifically detailed Voodoo deformer Delta Mush. Delta Mush smooths arbitrary deformation of a polygonal mesh without smoothing the original detail of the model. Developed in 2010, the tool allows Rhythm & Hues artists to use what the presenters described as simpler binds but coarser deformers – with the rigs and deformations remaining lightweight.

Check out the Delta Mush demo video below:

Modeling Tools at Disney Animation

This paper from Walt Disney Animation Studios’ Jose Luis Gomez Diaz and Dmitriy Pinskiy looked at the various tools the studio had developed and integrated into Maya for its animated films.

A tool called Dragnet is employed as a series of brushes to build and clean up model topology. Another known as dPatch generates light-weight quad meshes from hi res models such as those created in ZBrush. Perhaps the most recent tool developed at Disney Animation is a UV shell called Retopology, specifically built for use on Big Hero 6 to deal with clothing.

Disney had already integrated Marvelous Designer into its cloth authoring pipeline, with Retopology aimed at getting output from Designer and producing a more usable poly count and mesh. The team took advantage of the panel-based workflow in Designer which enables fast garment design and higher complexity and better quality clothes, but then need to do things such as determine boundaries on the panel UVs and allow for replication in order to produce useful and workable meshes.

Computer graphics and particle transport: our common heritage, recent cross-field parallels and the future of our rendering equation

Eugene d’Eon, of 8i (formerly of Weta Digital) presented a thought provoking talk on the way other fields of science and research have tackled many of the same problems we as an industry face today. His amazing personal journey on linear transport theory has referenced vast amount of literature from fields such as nuclear physics. Watch for an upcoming special fxguide.com story just on this talk soon.

Houdini Engine: Evolution Towards a Procedural Pipeline

Many people have heard of Side Effects Software’s Houdini Engine, but not a lot knew its origins. This paper from Ken Xu and Damian Campeanu traced Houdini Engine’s creation from the initial idea of Side Effects wanting to get more into the games industry to how Houdini Engine became a tool to help with procedural approaches in games, CG and VFX.

In 2012 a new team at Side Effects was tasked with getting into the gaming industry – somehow – utilizing the powerful Houdini software that was already a mainstay in VFX. But just introducing Houdini into a games production pipeline was not necessarily going to work, since FX creation with that tool was likely slower than required (had to be real-time). Other animation tools were already in use at many games studios, too. However, Houdini’s ability to help with large environments and to do geometry processing (across what could be multiple platforms) were things the team thought promising avenues.

But how would they position Houdini in all this? Could they add features to the software, for example? In the end they realized that data transport was something worth pursuing, and specifically this become the idea of improving the FBX interchange format. The one problem was that this was going to involve lots of processes to pull out FBX material for game engine conversion – too slow. Instead, Side Effects realized that ’the value is in the recipe’ – meaning that instead of a polygon, say, being the output that could be shared from Houdini, what should be shared is the node network representing how something could be constructed procedurally. And Side Effects already had a way of presenting that Houdini node network – the Houdini Digital Asset (HDA).

The next step was deciding on an appropriate API. There were two choices – the Houdini Development Kit (HDK) API and the Houdini Object Module (HOM). Both, however, were deemed too complex and so a new API called HAPI was introduced that only made around 120 API calls instead of thousands. It also assumes no prior knowledge of Houdini.

Ultimately, Houdini Engine now lets artists load Houdini Digital Assets into various digital content creation apps like Autodesk Maya, Cinema 4D and Unity. What was incredible about this was the development team for Houdini Engine had come in with little knowledge

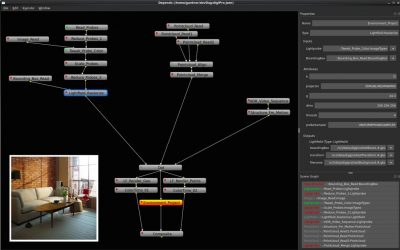

Depends: Workflow Management Software for Visual Effects Production

Andrew Gardner and Jonas Unger from Linköping University, Sweden produced this look at Depends, an open source multi-platform workflow management tool that originated out of photography and CG work their unit had been producing, including for photorealistic furniture shots in IKEA catalogues.

The workflow can now be downloaded from www.dependsworkflow.net and relies on a dependency graph and scene graph approach to organize files, control parameters, show how certain changes affect other changes among several other things.

Can We Solve the Pipeline Problem?

J.P. Lewis from Weta Digital presented a paper on the complexity of pipelines. The paper drew from known mathematical principles and theorems, such as showing pipelines themselves are very much computer programs, they branch, they have variables, involve polymorphism (simulation) and data structures. Furthermore we know that at some level a program is just maths. This coupled with various theories about maths such as the Halting principle.

All of this could perhaps be summarized as:

- pipelines are really programs

- programs are really maths

- maths can’t be absolutely proven

…or in other words “pipelines are hard”. The paper drew on a wide range of complex mathematical principles from Rice’s theorem, to probability.

As one of the paper’s reviewers expressed when Lewis first submitted to DigiPro: “Is it interesting – yes. How will it help someone do pipelines when they returns to work on Monday? Beats me!”

And as one member of the audience commented during question time, in essence Lewis was proving the old pipeline proverb (!) “Pipelines are like the dishes, you clean them up – but you know they are just going to get dirty again.”

Lewis closed with one very popular theorem – he proposed from all of his research there was Lewis Law of Full Employment: which can be paraphased as – this stuff is so hard that Mathematicians, Compiler Programmers and Pipeline Writers will always experience full employment and will not be replaced by computers.

CG Pipeline Design Patterns

Bill Polson of Pixar Animation Studios started recently to write a book on Pipelines. Unfortunately he quickly discovered that when trying to draw a pipeline, he lacked the tools. After extensive investigation he discovered that there is really not a very good visual language for graphing out a pipeline. Given the complexity of modern pipelines engineers and researchers alike could benefit from a visualization of the complex process, after all for many companies the very process of making a film – their “pipeline”, is both the source of serious IP development and also a source of competitive advantage.

Armed with a desire to be able to use any such system both electronically and on a whiteboard, Polson set down a path of defining a graphical language for Pipelines. With the full disclaimer that he had not yet perfected the graphical solution, he outlined his simple but powerful solution by showing the entire Pixar pipeline on one informative overhead.

The Brush Shader: A Step towards Hand-Painted Style Background in CG

OLM Digital, Inc’s Marc Salvati, Ernesto Ruiz Velasco, Katsumi Takao were behind this session on simulating Photoshop functionalities in ‘Brush Shader’ for adding detailed shading on top of rendered images. In particular, it was used on OLM’s production of the Pokemon movie. The benefits of the Brush Shader allows artists to have more elaborate camera moves than would be possible from normal matte painting approaches.

Time Travel Effects Pipeline in “Mr. Peabody & Sherman”

DreamWorks Animation’s Robert Chen, Fangwei Lee and David Lipton prepared this talk on the creation of the magical wormholes in Mr. Peabody & Sherman. These were inspired by the mathematical fractal flame images but had to remain art-directable and animatable. To create the tunnels, artists first planned out tree-shaped paths and rings. Effects then took the paths and resampled them into points with equal intervals and grouped them into clusters by calculating the point cloud density.

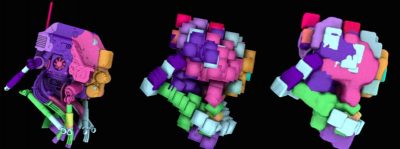

Choreographed droid destruction on Elysium

Image Engine’s Greg Massie and Koen Vroeijenstijn were responsible for this talk on destroying a droid from Elysium. Here, the FX team fractured a droid model made up of 1.6 million polys and 3200 separate shapes into 8000 pieces (800 visually interesting chunks). Then special tools allowed for animating droid chunks and bullet waves using proximity queries – the chunks also matched the inherent hierarchy of the droid body.

A single RBD was then done, using instanced cubes onto each piece of fractured geo – the chunks were converted to an approximate signed distance field. The effects process was chained together in a 135 node dependency network for rendering.

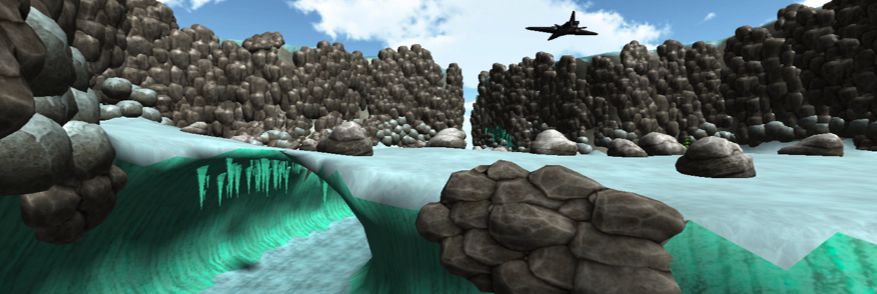

Arctic Ice: Developing the Ice Look for How to Train Your Dragon 2

The final presentation of the day looked at this paper by Feng Xie, Mike Necci, Jon Lanz, Paolo deGuzman, Patrick O’Brien and Eduardo Bustillo from DreamWorks Animation detailing the different looks of glacier ice required in Dragons 2.

The final presentation of the day looked at this paper by Feng Xie, Mike Necci, Jon Lanz, Paolo deGuzman, Patrick O’Brien and Eduardo Bustillo from DreamWorks Animation detailing the different looks of glacier ice required in Dragons 2.

Some of the most interesting parts of this talk were the different levels of translucency provided for and the use of AOV passes (a first for Dreamworks Animation) to orchestrate a multi-pass rendering approach to the final shots.

SIGGRAPH 2014 – Day 1

Even on Day 1 at SIGGRAPH there were some killer presentations, including USC ICT’s talk on digital faces work, plus a number of production sessions from VFX Studios

Digital Ira and Beyond: Creating Photoreal Real-Time Digital Characters

Last year at both GDC and SIGGRAPH, audiences got to see the real-time demo from USC-ICT, Nvidia and Activision of Digital Ira. This real time rendering of an interactive face of USC-ICT researcher Ari Shapiro, was also extensively covered here at fxguide. This year as part of the courses program a panel of researchers and programmers from ICT and Activision worked through the creation process from scanning to rendering, pulling in related historical elements and hinting at future projects.

9am on a Sunday morning before the main SIGGRAPH has started, and two days before the trade show starts may be one of the hardest slots to fill on the SIGGRAPH panel, but the session put together by ICT’s Paul Debevec was packed. From multiple Oscar winners in the front row, to former students and current researchers from around the world, the program detailed the complex work that was done to produce not only amazingly vivid images of a human face, but the tricks and techniques used to make this run in real time on domestic graphics hardware.

In a time of crushing schedules and squeezed budgets, increasingly people are turning to joint partnerships with leading universities to provide basic research and fundamental advances. In this case, Digital Ira has proved how successful that kind of collaboration can be.

Capturing the Infinite Universe in “Lucy” – Fractal Rendering in Film Production

If you’ve seen Lucy, then you’ve seen ILM’s incredible visual effects work representing the titular character’s ‘out of body’ experiences after a new wonder drug leaks inside her. But what you haven’t seen is a bunch of fractals work the studio did for some of the film’s ‘big bang’ sequence that didn’t make it into the film film. In this session presented by FX TD Alex Kim and CG supe Daniel Ferreira, ILM showed some of those shots and how they were made.

To deal with the highly detailed fractal imagery required – which often come with high polygon counts – ILM turned a hybrid/OpenVDB representation of their fractals. The fractal geo was represented as particles within screen space, meaning the studio could treat each particle as a ray.

The approach was implemented as a fractal ray marcher inside Houdini as a plugin. During ray marching, the additional properties of each particle were calculated and stored as particle attributes to be used during shading. ILM generated a mesh/volume by scattering on low res geo that was ‘dilated’ to include fractal geo. Particles were ray marched to generate a point cloud that was turned into a mesh using OpenVDB.

The results were fast, and promising. In the above image, ILM used 12 particles per pixel sample, taking 20 minutes to calculate particle position per sample (2,211,840 particles) on 4GB, 4 cores.

Got Crowds?

This multi-presentation on different crowd solutions featured Framestore presenting on their Tengu monks work for 47 Ronin, MPC delving into the flying armada for Guardians of the Galaxy, Imageworks showing their CRaM tool used on Edge of Tomorrow and Pixar demonstrating how they have ramped up their crowd toolset in the age of raytracing. Suffice to say, there was killer work on show from killer studios. We’ll have more on MPC’s work, in particular, in our Guardians coverage.

Technical Papers Fast Forward

Picture this: a major exhibition hall as full as it can be with SIGGRAPH attendees, and the exhibition hall next door also full as an overflow room. That’s the allure of the Technical Papers Fast Forward event in which scores of technical paper presenters try and convince attendees to come to their talk…in only 30 seconds.

Some highlights:

[…] SIGGRAPH 2014 – DigiPro and Day 1READ ORIGINAL SOURCE ARTICLE HERE: http://www.fxguide.com/quicktakes/siggraph-2014-digipro-and-day-1/ […]