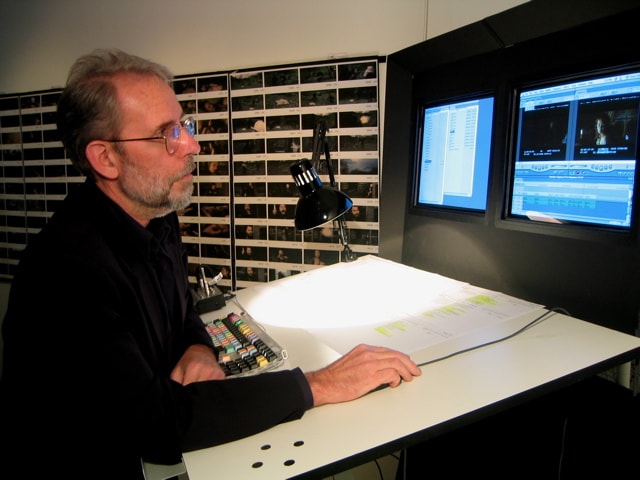

Walter Murch is a household name in filmmaking. The accomplished film editor and sound designer has worked on such classics as The Godfather films, Apocalypse Now and The English Patient. We recently met Murch at the VIEW Conference in Italy where he spoke about his long-time association with digital editing systems – Murch was a forerunner in the use of Avid for feature filmmaking, and has since gone on to use many different editing systems. Here’s our conversation about some of his insights into the digital world.

fxg: What was your first encounter with an electronic or digital editing system?

Murch: This was in 1968 and it was the first time I met Francis Coppola. He was a legend in the film student world because he’d graduated from film school and he had made a feature motion picture called You’re a Big Boy Now. He had also turned that film in to get a Masters degree.

He and George Lucas came by and said, ‘Quick, let’s go up the street to Memorex’ because CMX and Memorex had built an editing machine that was computer controlled. It was running big disc hard drives, bigger than an LP, and there were ten of them stacked on top of a computer that was the size of a washing machine and there were five of those. That was enough to have five minutes of film in black and white at that time.

The idea was that it was going to be used for editing commercials. When you got the clients in you could look at it and very quickly make changes. It was cheaper to conjure up this relatively huge technological beast because those commercials were so expensive and the decisions so corporate and complicated – the clients would say ‘Now we want to see the one with the rose and the Coca-Cola bottle’ and it could be brought up immediately.

We left that meeting and I went back to work editing on a Moviola and I thought, this is great, electronic editing will be everywhere in five years. A year or two later we had all moved to San Francisco and we were Zoetrope Studios and Francis got the job to direct The Godfather. He asked me to put together a workflow to edit The Godfather on that machine from CMX. Francis loves technology, and I love technology. It was certainly a challenge to think about how to do that at that time.

We sent the proposal to Paramount and they of course dismissed it as the ravings of film school graduates and told us to get serious! And in fact I was totally wrong, it wasn’t five years before we were editing like that, it was 20 years. But by the early 1990s digital editing really did begin to emerge and by The English Patient in 1995 I was editing my first Avid feature. That was the watershed year in which there were more films being edited digitally than conventionally.

There were two breakthroughs, really. There was the ability to work on two machines at the same time or three with using networks. And storage had gotten so fast and inexpensive that you could store all of the film all together and access it instantly. Prior to that, say with The Godfather Part III, which we edited on the Montage system, you had to load in video tapes of only that section of the film. If you wanted to get an image from the end of the film, you had to do some kind of very complicated rigmarole to do it. It was very cumbersome and I’m glad we don’t do that anymore.

fxg: Did you trial other systems before you came to work on the Avid?

Murch: No, the paradigm before Avid was having the media itself offline. It was stored on some other medium and it was the computer that was the traffic cop that told that media what to do. The big breakthrough on Avid was that, on the same machine, stored on the same hard drive as the media, are the instructions for what to do with the media.

As late as Apocalypse Now Redux, which came out in 2001, which we edited on the Avid, Francis was in my room watching something I’d done and in the end when we finished he mused philosophically and said, ‘I never thought we would get to this point.’ That that machine has the media and the instructions for what to do with the media. Nowadays we don’t even begin to think about that as an issue, but when you look back and see where we were coming from, it’s still remarkable. Even as late as the year 2000 which was five years after the triumph of the Avid, it was still a headshake to realize it could all be on one machine.

fxg: You’ve worked on several editing platforms, from the Avid to Final Cut and Premiere Pro – has that transition to each been relatively smooth for you?

Murch: I just dive into it. I do a couple of days exploring, just to make sure there aren’t any real hidden snakes in there. And then i read up about it and talk to other people. When I made this most recent shift to Premiere I talked to Kirk Baxter and Angus Wall. I also talked to the Cohen brothers. What I got from these guys was that Premiere is really good, it’s really evolving, there are still some things that will drive you crazy – but you can do it. The great thing is that Adobe is working very closely with filmmakers, listening to them and turning those ideas around in a matter of months. Already I have proposed things to Adobe that are now in the program.

fxg: What do you like in particular about Premier and the non-linear systems?

Murch: Well, I have to say the paradigm Adobe have is very similar to an idea I pitched to Apple back in 2002, which was the metaphor of the hollow prism. We’re very familiar with this from the Steenbeck, where you have a prism that has facets and you have a lens in the hollow in the middle of that circle and that’s casting light from below, bending it through a mirror and shooting that light out through one of the faces of the prism which is carrying the frame. The point of it is – my suggestion was – think of the film as the thing in the middle and the facets of this hollow prism of different ways of approaching that material. So, I’m editing and I have a set of tools, and now I want to do more sophisticated sound work, well then all I need to do is go ‘click’ and I rotate the prism and I’m looking at the film through this other facet. Then I do my changes and they’re preserved and I go back to the other facets. It’s the same thing with VFX or color grading.

fxg: You’ve clearly embraced digital filmmaking but is there anything you lament about the way things used to be done?

Murch: One thing that comes to mind is the dailies process. In the old days there was no video tap, so the only person who saw what the camera was going to be seeing was the camera operator. If the take was good the camera operator would look at the director and go ‘OK’ and the director had to take that at face value. But what it *really* looked like you wouldn’t know until the next day. When video tap came in in the early 80s we could at least begin to see at least on the level of blocking that the framing was right. It was black and white and low-res but it was the beginning of the process that has now become a very clear image of what you’ve shot. Certainly if you’re shooting digitally the video feed is immediately sent to ten different plasma screens around the set. You sit in these little mini-theaters almost like a knitting club doing their work and watching.

You’d think at the end of the day you’d seen everything, and at a certain basic level you have, but you haven’t seen it with a pure mind – what we would call an almost religious mind. In the old days what happened is, you would shoot, it would go to the lab and it would come back and it would by sync’d up, the B shots separated from the A shots and you’d go into a theater and the heads of departments – the director, cinematographer, editor, script supervisor, producer etc – would have no other agenda than to watch, sometimes painfully watch, what had been shot the day before. And here they would absorb the vibes, good and bad, of how that made everyone feel, and talk about, well, we’re not going to make that mistake again, or that didn’t work, that’s really great etc etc.

There was a communal part to the process that’s in danger of being completely lost. There are very few people who will do that. So now the dailies as such are watched only by the editor and by the studio. Occasionally the director will tap into it and scan quickly through it, but rarely looking at 24 frames per second.