Lorne Peterson is one of the world’s most well-known model makers in visual effects, getting his start at ILM on the Death Star for Episode IV: A New Hope and continuing to lead innovation at the ILM Model Shop for the next 30 years. We caught up with Lorne at the VIEW Conference in Italy where he was presenting a history of the Model Shop as part of ILM’s 40th anniversary celebrations, and asked him just what happens to models and miniatures after they’ve been shot, and also about a few of his key memories in VFX.

fxg: I’ve always wondered what happened to the miniatures after you’d finished with them – you do see some them displayed still at ILM of course and some film studios have them, then others make it onto eBay and auction sites, but generally what was your experience?

Peterson: Well, anything that was Star Wars related, George Lucas would decide if it got saved. The Mustafar miniature, for example, did not get saved. What do you do with something that big? It just got thrown away. Other times the studios that hire us to do the show want the model. We always thought we should be able to say yes or no, but the studio would say, well, we paid for it…

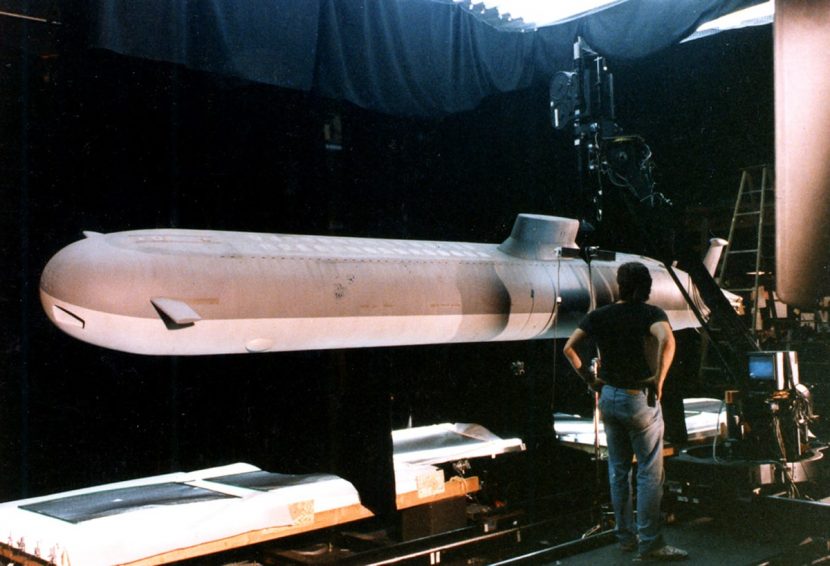

At the Presidio where ILM is now, the big submarine from The Hunt for Red October was there. Then there was this documentary made that had shots of the submarine. The studio was watching the doco and said, ‘That’s our model! That could be in our office!’ They phoned up and said they felt like that was their model and they just left it behind ten years ago and now they want it. So they packed it up and we shipped it back to them.

fxg: They really did?!

Peterson: They really did. Sometimes with stop motion puppets, for example, the armature underneath will always be ILM’s but the skin is the studio’s. When we’ve done things like that and cut the skin off and sent it to them in envelope I think the studio’s been like, ‘Hmm, that’s not what we wanted…’

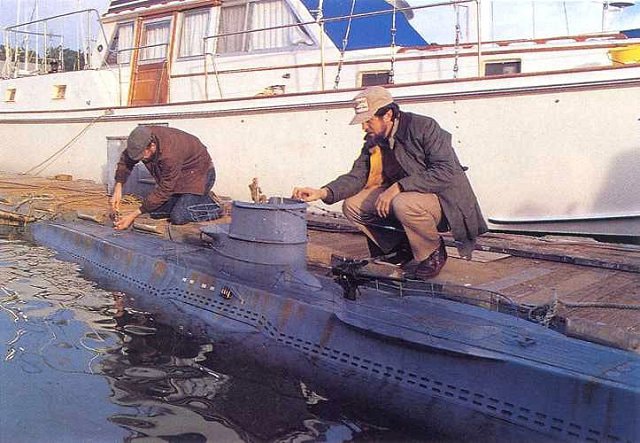

Here’s another submarine story. The submarine for Raiders of the Lost Ark was originally used on the film 1941. It was a German U-Boat. We re-used it but changed it a little bit. It’s the one which has a little dummy of Harrison Ford on the periscope and we took it out into the Bay and there was an island we used out there to represent the German base. We dropped an anchor and put a polly underwater and pulled it along so that it looked like it was sailing towards the island. We thought it would be a great idea to donate that to the Science Museum in San Francisco. Later on, five years later, we realized we needed a U-Boat for something and we went to the Science Museum and they had it under a tarp, which had started to rot away after years under the sun. Rain had swollen all the parts of the miniature and i was totally ruined!

We really wanted the ships from Pirates of the Carribbean to stay at ILM. I spent a lot of time doing the Chinese Junk. We did a 20 foot version of the Endeavour too. It was just so beautiful. One of the fun things about that model was that when we shot it out on the stage, you always have modelmakers who stay with the model to do all the things it’s supposed to do, like unfurl its sails. So I was one of the modelmakers who did that. It was like being a miniature sailor. We suggested they film with the sails furled and do all the shots with it furled from the right and then the left and then the front, and the shoot with the sails unfurled. But that’s not how they shot it – we had to keep putting the sails up and down, the gun flaps up and down and moving the model. There were hundreds of little ropes with little pegs to move around. It’d take us two and half hours sometimes to reset the sails.

fxg: The nature of model building was always very handcrafted, of course, but what building materials and technologies changed the most during your time at the Model Shop?

Peterson: The materials stayed the same, pretty much. We used everything from baking soda to aluminum to steel to plastics and plywood. The two big changes were when we got laser cutters. The first laser cutter we got was small, about 4 feet by 3 feet. Then eventually we had one that was 9 feet by 5 feet. The big dirigible, the airship in Indiana Jones, was made with the laser cutter. All the structure on the inside was birch plywood about an 1/8th of inch all laser cut, and then the holes were put in by the laser, and we put steel cables and tensioned them just like how a real dirigible is made. Then 3D printers showed up later and also changed the way model pieces were made.

On Attack of the Clones, they had the Kaminoan’s who made the clone army – the hallway they walk through with Obi-wan was done with a laser cutter. I personally wasn’t working on that particular model, but I remember telling all the artists who were laser cutting everything was that one of the benefits of model making was you could make things very irregular. You could have one thing further down stick out with a pile of something. But they tended to want hallways that were absolutely perfect without any variation. The problem is that I knew CG could replace that with a little bit of time. If the Model Shop only made models that looked like CG models only a couple of years earlier, we would really lose out. Whereas if we made them quirky and unusual, where say every fifth panel would be a little bit off or we added in a doorway or a pile of stuff, then we would benefit from it.

fxg: Do you think, though, that that kind of handcrafted approach to modelmaking did, in the end, inform the process of good CG modelmaking, by adding in imperfections?

Peterson: Yes, exactly. I mean, when you look at a big skyscraper, the windows aren’t absolutely perfect. They vary just a little bit. Sometimes we might have had to build a building that looked mirrored and you’d get a big sheet of plastic mirror and then you’d just glue on the window frames. The problem with that is, the mirror behind it is reflecting too perfectly. And that isn’t the way it works. You need those imperfections.

The thing is too, the digital effects guys would take pictures of our miniatures for textures when they had to replicate them. There are digital painters who would go out and gather reference of every rusty wall, finger prints on plastic – everything. That would give them a menu of every kind of texture.

fxg: That’s interesting – do you remember one particular project you worked on where there was a really nice cross-over behind the model work and CG?

Peterson: To be honest, we always had a nice relationship with the CG guys. There was no animosity between us. Mustafar is a good example. That was a great combination of CG and model, even though there were 400 shots there. And then there was some live action volcano stuff too because they shot reference of Mount Etna exploding. They did a lot of CG animation of lava falling on top of beams and splattering. It was just an incredible group of shots and when you see it all put together people can’t believe that it’s not all lava or CG or miniatures.

A friend of mine who started in the Lucasfilm Computer Division, which was before Pixar – I asked him how long are real models going to last? He said if it’s a moving shot, CG will win, if it’s a totally still shot models will probably win for a while, but that CG would catch up. It did, certainly, but there’s lot of miniatures still being used.