With three Transformers films already under visual effects studio Industrial Light & Magic’s belt, Age of Extinction still managed to be eclipse them all in terms of effects shots, shooting locations, crew size, stereo delivery and sheer scale. ILM visual effects supervisor Scott Farrar describes the show as the “heaviest data wrangling picture I’ve ever done, the largest in ILM’s history. It was the largest crew I’ve ever had – 500 people. It was IMAX and 3D so you’re rendering twice as much at least. Our work is about 90 minutes worth of the movie.”

In this article fxguide explores ILM’s new challenges on the Michael Bay film, from ramping up on robot facial animation, to the new KSI-bot ‘hypno-transformations’, to creating the dinobots, crafting the enormous effects simulations as Hong Kong is ripped apart and building vast spaceship interiors.

For more on Age of Extinction, check out our in-depth fxpodcast with ILM’s Scott Farrar and Pat Tubach.

Ramping up on robot animation

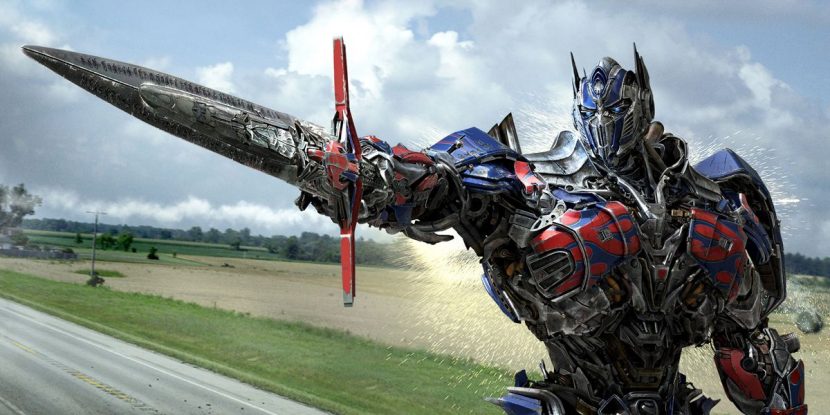

With more robots to animate – and some like Optimus Prime with multiple body styles and multiple levels of damage seen as the movie progresses – ILM looked to give more control to its 60-plus animation team on Age of Extinction, led by animation supervisor Scott Benza. That extra control extended in particular to facial animation, where existing ILM rigging tech was expanded upon to help the process.

On the previous Transformers film, Dark of the Moon, ILM had animated the character of Sentinel Prime with a high degree of facial expression. “We had put an actual geo mesh under Sentinel’s face to rig it with shapes to drive the facial animation,” explains ILM lead creature TD Jacob Buck. “This new film built off of that but we needed it to scale. So I built some stuff in BlockParty 2, our rigging package, to help facilitate that and automate some of the processes so it would scale to six to eight characters.”

BlockParty 2 is ILM/Lucasfilm’s proprietary procedural rigging system built in Maya that allows riggers to create shareable rigs and then re-use these components. BlockParty was initially implemented for the first Narnia film at ILM, with the second incarnation developed for Noah, which greatly assisted that film’s ‘creation’ time-lapse sequence. Age of Extinction was the first ILM show that allowed artists to re-use parts, such as pistons, across robots. “It really let us do the facial rigging setup,” notes Buck. “It saved us a ton of time because then we can proceduralize that and be ready to rig the rest of the face up.”

This use of BlockParty 2 then hooked into ILM’s Fez rig – the studio’s Facial Action Coding System (FACS) implementation. “Artists have all the shapes they can dial in,” says Buck, “and they can dial in the correct expression on the transformers themselves. We also built another layer on top of that where they can hand-manipulate some stuff with curves as well. Obviously they’re not exactly human, so they need to be able to change some of their poses a little easier with tweakers. Just because we can drop a proceduralized face in, that only gets us a step there for the extra animation control, but there’s so much deformation happening on top of that.”

For ILM animation director Rick O’Connor, the advent of much more facial animation in the film was, in fact, a welcoming prospect. “When we first got the screenplay and saw how much the robots would be talking in this film,” he says, “it really made us animators excited. Sure we like to do robots fighting, but any time you can get them to emote and find emotion to go along with the exposition of the film, it’s a great treat for someone creative.”

One of the most expressive, and complicated, robot faces in the film was Lockdown’s, who was voiced by Mark Ryan. “We used Mark Ryan’s face as a heavy anchor on how his face should move,” explains O’Connor. “Using his face as reference, we got a pretty bang-on match to the actor and I think that adds a heck of a lot of detail to the performance because we’re pulling up nuances to what the actor did.”

Voice actors were recorded on video while in ADR sessions, with ILM employing a system to map the two-dimensional image onto the face of the robot rig for animation. “It’s very early in its development this process,” outlines O’Connor, suggesting further work will be on-show for the upcoming Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. “We could take the facial animation as far as we could with the actor to keyframe on top of that to achieve the perfect goal we were aiming for.”

Age of Extinction also represented the first time Michael Bay has utilized a virtual actor on stage and a simulcam system to produce animation (certain fight sequences also made use of fight choreographer Garrett Warren and a team of mocap performers to stage robot battles). The simulcam process was used in particular for Lockdown’s Night Ship environments. “He had an actor wearing pajamas – the mocap suit – with the reflective ballsm and in front of him he saw Optimus Prime,” relays O’Connor. “So he was able to create shots for the first time on the stage with an actor looking like Optimus.”

For Bay that technique was surprisingly effective. “He was so happy with the process,” says O’Connor, “that he looked over at Scott (Farrar) and Scott Benza, and he said you know what, ‘I don’t think I need you guys anymore!’” O’Connor adds that when Bay asked the ILM team who the actor playing virtual Optimus was going to be and they said it would be an animator, Bay jokingly replied: ‘Oh, you just blew the dream – now I know that Optimus Prime is an animator – he’s supposed to be a warrior!’”

Another animation challenge of course lay in the numerous mechanical transformations seen in the film. ILM relied here on its existing TFM tool which had been re-written during production on Pacific Rim. “The TFM tool lets us create rigs in-scene,” describes Buck. “You can basically change the parent hierarchy on the fly, so it lets animators and some of the creature guys re-parent everything and set up a new deformation stack to help set it up for the transformation. We re-wrote it speed using instancing in Maya for the shape nodes to get some more speed out of it ready for Transformers 4.”

“Animators can literally do whatever they want with the TFMs,” adds Buck. “If they want to pick five bolts and transform them one way, and then pick something else and do it another way, they can completely re-order the entire stack however way they please.”

A new kind of transformation

New characters and new robots are the trademark of each Transformers film, and are always of course a major challenge for ILM. Age of Extinction sees new prototype transformers developed by Kinetic Solutions Incorporated (KSI) with transformium – the material transformers are made of. Stinger, who transforms into a 2013 Pagani Huayra, is one of these robots whose shapeshift from bot to car involves a cube and strand-like transformation – something ILM dubbed ‘hypno-transformations’.

“It was very difficult to figure out what the look should be,” notes Scott Farrar. “We’d do full transformations where it would break down into cubes and bits with wire frames, or sometimes just ripples through the body parts, as if there’s a sub-strata of metal framework and you’d reveal that a little bit.”

“It was really fun to come up with a particle simulation way to move these strands through the air and how many should there be,” adds ILM associate visual effects supervisor Pat Tubach. “For instance, a car turns a corner, it starts to form into a robot, and we would just fly the robot from point A to point B – and then the performance would actually end with the robot doing something cool. So you wouldn’t end up with a staged looking thing where he had to sit down and be morphed into something – you would actually get a performance where he rolls into the scene.”

Part of the challenge was how much transformation to show as the robot pieces moved in space. “Most of the transformers transform from robot to car on the spot,” says Rick O’Connor, “but these things can travel a long distance while they’re transforming from one thing to the other. When they’re in mid-transformation and turn into a robot, we can hit some pretty cool dynamic poses as all their weight and pieces come back together. It was an elegant dance in the air.”

To help work out the large scale hypno-transformations, ILM worked firstly on the much smaller lab version, in which a ball of transformium is shown exploding into cubes, wires and later guns and other props. “The look was driven by hand-controlled simulation parameters,” explains CG supervisor John Hansen. “We would set up basic building blocks in animation and those would drive different transforms which would be a lattice cage and had a little bit of wobble to it, and lots of channel massaging to give it the right squash and stretch and pull and lag. Without a lot of that hand-tuning we couldn’t get that hypnotic feel to it.”

ILM’s approach to the KSI-bot animation, then, had three different ‘cycles’ handled in Houdini and rendered in RenderMan. “The biggest challenge,” notes Hansen, “was cutting up the geometry, literally controlling how every single polygon would travel through space, extruding them, creating bevels for an interesting shading pattern and having all the textures on every single facet and then blending to the raw transformium cube as it traveled through space. And then transitioning the material back to the robot or vehicle piece that was being assembled.”

“There was the dis-assembly, there was the strands, the tendrils that travel through space and there was the re-assembly,” adds Hansen. “We had to simplify each step and do a point-based representation of what the dis-assembly timing would look like, where it would travel through in space. Another artist specialized on the tendrils made of cubes and had different wave patterns traveling through them.”

The re-assembly part of the transformation involved the shrinking down of the cube faces, with robotic parts growing from inside a beveled cage and snapping into place. “When we completed the re-assembly we saved out per frame caches of the geometry with texture assignments, handed that to our lighting department and then they worked their magic on it,” says Hansen.

Dino-action

When this year’s Super Bowl commercial for Age of Extinction aired, a scene of Optimus Prime atop the fire breathing Dinobot Grimlock quickly became one of the film’s signature images. “The first thought I had when we started doing rough sketches and turning it into animatics,” recalls Farrar, “was, ‘Wow, here’s a chance to have Optimus Prime ride into the rescue literally – very heroic – on his steed just like a John Ford Western.”

And if there’s one visual effects company aptly suited to make transforming Dinobots, it’s ILM. The studio relished the opportunity, ensuring that they were infused with individual personalities. “You’re looking to other animals for guidance,” outlines Pat Tubach. “The triceratops is going to appear to people with more dog like qualities – always digging and scratching and ramming his head into things.”

Filming plates for the Grimlock / Optimus fight.“We were making dinosaurs with alien technology,” adds Rick O’Connor, who notes that Michael Bay wanted the Dinobots to not necessarily look or act like traditional dinosaurs. “So for Scorn the Spinosaur he wanted him to jump into battle using the spikes on his back. Or Grimlock will jump up like a whale breaching out of the water then he’ll extract his jaws like a shark to snatch a guy out of the air.”

The film’s opening sequence includes a look at real dinosaurs, too, in a prehistoric earth setting as an alien race seeds the land with transformium. Scott Farrar supervised a second unit IMAX film shoot in Iceland to serve as background plates for these scenes, which were then augmented with effects. “The bombs of transformium explode and you get a rush of metal moving across the surface,” SAYS Tubach. “It was a similar feeling to the lava freezing in Star Trek – we’ve got a rush of molten metal moving across the surface and then hardening very fast. As the dinosaurs get in its path it hardens almost instantly.”

(Even more) realistic effects sims

Although ILM had moved into a predominantly physically based shader approach for their creatures on recent films, Age of Extinction represented a major move for the studio into image based lighting in volumetric effects. And it was used in a big way – from Dinobot ground interaction to building destruction and the tearing up of Hong Kong via Lockdown’s magnetic beam – all the while having to often match the practical effects realized by special effects supervisor John Frazier’s team. “We wanted to get a better integration with the hard surface lighting as well as the background plates,” says John Hansen. “For example, with really thick smoke simulations we would have a rim light that made the smoke very well defined but we can never really get light into the crevices, especially from the front views.”

On Pacific Rim, ILM had been able to bring out significant detail in smoke effects with an environment light rendered in Houdini’s Mantra, but the performance had been relatively slow and only used on a few shots. In order to speed up the process for Age of Extinction, engineers implemented a physically based lighting model in the studio’s Plume software – ILM’s hardware accelerated GPU-based volume sim and renderer. “That was an incredible win,” notes Hansen, who says the team moved from 4 GB cards to 6 and 12 GB cards. “On the new generation of hardware we were able to do image based lighting with volumes at the same speed as regular spotlight volumes on the older hardware.”

On set practical explosions had to be matched by ILM’s digital work.A further addition to ILM’s pipeline was OpenVDB – the DreamWorks Animation-developed open source library and suite of tools for the efficient storage and manipulation of sparse volumetric data discretized on three-dimensional grids. “We have OpenVDB collisions now,” says Hansen. “That’s given us the ability to get much more detail with about the same amount of memory and computational expense in proprietary and third party software, and where we can exchange data has helped artists as well.”

OpenVDB became useful, for instance, in capturing fine effects details on robots in the film. “There’s a sequence where Grimlock gets punched by Optimus Prime and he goes tumbling into the forest and you see this very hero close-up of his face covering the whole frame,” states Hansen. “There’s little streams of debris pouring off every crevice and it’s because of OpenVDB that we were able to capture all of his facial detail in the volumetric collision, whereas before we would have had to rely on planar polygon collisions.”

Other kinds of dinobot destruction were carefully realized with close attention paid to how they tore up the Hong Kong streets. “We really wanted to convey how heavy and massive and present these robots are,” says Hansen. “When they were walking on the ground, they would crack the pavement. When they were running they would kick up mounds of dust. When they fell down they would eject a wave of dust and debris and rocks and soot into the air.”

“We developed a very streamlined procedure for identifying the intersection of the characters in the ground plane,” continues Hansen. “That would generate automatically collision body emitters for instanced debris, dirt particulates, volumetrics and that was all rendered in deep and be able to be composited in deep.”

In fact, with so many volumetric effects and complex transformer action, ILM relied on a full deep data pipeline through to rendering (which made use of Arnold, RenderMan and Mantra) and compositing. “We couldn’t have got this show done with a traditional 2D holdout pipeline,” recalls Hansen. “The compositors ended up doing a lot of pre-comps so they would merge the volumetric deep layers and then save that out, and then do a lot of color tweaks and integration on top of that.”

Of course, most of the destruction effects occur in the Hong Kong sequence in which Lockdown’s Night Ship magnetically pulls up metal objects, including robots, cars and even large ships into the air before dropping them. And amongst that sequence are fights taking place in and through buildings. “A destroyed building requires a look at the architecture,” notes Scott Farrar. “We study what it’s made up, so we look at is that just a facade of an aluminum panel over cement or is it front of girders, so you know what you’re going to break apart later. The architecture dictates what we’re going to do.”

“Building destruction has always been one of our crown jewels – we love to do building destruction,” admits Hansen. “Our rigids team are specializing in rigid based destruction where they use flesh sims, cloth sims, rigid sims. They layer in lots of different methods of simulation to convey bending, twisting metal, vibrations of the structure, glass shattering, i-beams smashing. The effects team will layer in all the different secondary simulations on that, whether it’s glass sims, particulates, concrete debris and dust. Lots of fireballs – you can’t get enough fireballs especially when a Dinobot is scraping up the building.”

In terms of its effects toolset, ILM relied on a combination of its PhysBAM solver plus Plume and Houdini, with rendering in RenderMan and Mantra. Shots featuring massive pieces of buildings, cars or ships in the air were achieved initially via a simplistic simulation approach. “It was usually just a point based particle simulation for the bulk of the process work,” explains Hansen. “We instanced different metallic geometry onto those points and gave them a rotational lift or a fall. We had a few hero pieces that were right in front of the camera – in that case it wouldn’t be an instanced point based asset – it would be a hero asset with a car rolling up and the door flipping open, or a bus lifting right off the ground.”

See shots featuring ILM’s destruction fx in this TV spot.Throughout the chaos, ILM animated various spaceships and vehicles, all requiring various levels of effects including thrusters and heat ripples. “Houdini has a really nice workflow for prototyping different looks through volumetrics,” notes Hansen. “One of our artists prototyped the look of that thruster in Houdini in a couple of days – really fast – and another artist spent the next couple of days wrapping it up into a template for everybody else to use.”

Lastly, the effects teams had their hand also in many forms of robot damage. “When a robot gets sliced in half, we layer in a shower of mechanical parts,” says Hansen. “We eject bolts and panels and pieces – we shoot our sparks and white smoke. If it’s a bad guy they shoot this liquid like robot blood. We put a lot of effort into art directing each bullet hit – whether it was a tiny spritz of sparks that last three or four frames, or if it was a shower of sparks and smoke or fire. In one case Optimus took missiles from Lockdown right through the chest. In that case it was showers of sparks, fire and smoke – we ran fluid simulations for that to make it feel more integrated.”

Building the Night Ship

Before audiences witness the destructive capabilities of Lockdown’s Night Ship, they see the craft’s mysterious side as its commander imprisons Optimus. The ship is seen firstly in a vast reveal over a wheat field, something Scott Farrar immediately saw as an ‘iconic shot’. “We got the artwork and I said why don’t we just assume the ship is so big, so colossal that it always has its own little weather pattern cooking around it.”

Farrar took that idea further for scenes of the Night Ship in flight over a slightly foggy Hong Kong, which actually added to its mystery by requiring artists to give it a slightly fuzzy and dim look. “It gives it a different color,” says Farrar, “and if we do our job correctly it should fit into our backgrounds. I think some of those shots look strangely real and surreal because of the lighting.”

Catch a glimpse of the Night Ship in this TV spot.The inside of the Night Ship was equally mysterious. “There’s all these nooks and crannies around the ship where you can’t exactly see what’s back there,” outlines Pat Tubach, “but it’s full of scary fire and electrical light going off and things happening that makes it seem like a very forbidding place. Not to mention there are cells all over with various creatures in them which we populated with robots and other fleshy creatures, just to pique everyone’s interest.”

Since much of the ship interior would be rendered as computer graphics, Bay invoked the aid of several artists to flesh out the ship using game model assets. “He had them in his office creating the inside of the ship, just the geometry,” explains Farrar. “It got pretty heavy, so heavy that we had to strip it down and make it simpler for us to pick camera angles – hundreds of thousands of pieces to figure out the corridors and pieces. That way Michael could dictate what his favorite views were and we could worry about lighting it later on.”

Production designer Jeffrey Beecroft created various mobile set pieces for the interiors for actors to perform amongst. Like other robot scenes, poles representing the height of transformers, sometimes with cardboard heads on them, represented the CG creatures ILM would be adding in later.

ILM made use of its ‘generalists’ pipeline to craft the Night Ship – this team is based in 3ds Max and V-Ray and has had a lot of recent success with detailed environment work. “There were some fairly large set pieces to indicate a cage wall or a pillar, but the majority of it was set extension of complete CG fabrication,” says Tubach. “Jeff Beecroft and his production design team had a fairly large set of imagery we would riff off – for example, a pillar or silos which looked like little nuclear silos in the ship, and we populated those things into the distance as a sort of design language.”

The effects team also had a hand in populating the interior of the ship with interesting action. “Instead of just a solid surface background,” says John Hansen, “we layered in rising steam vents or falling mist like pockets of dry ice, showers of sparks, water drips, pockets of smoke floating in the air. It was a way of giving dimensionality as the camera flies through smoke and gave a lot of character to the spaceship.”

When fxguide spoke to the ILM team, they had only just delivered the final effects shots for the film. It’s a project VFX supervisor Scott Farrar calls a ‘monumental movie in every way’ where dailies would last eight hours and work progressed between ILM’s San Francisco, Singapore and Vancouver locations, along with work done at Base FX, Method Studios, 32Ten Studios and stereo conversion facilities Prime Focus and Legend3D. “Every shot was dense,” he adds. “There wasn’t just a single robot in the frame, it was many robots with speaking parts. I’ve never had a movie like this!”

All images and clips copyright © 2014 Paramount Pictures.

Pingback: Age of Extinction: ILM turns up its Transformers toolset | Animationews

Pingback: Age Of Extinction: Would You Like A Look Behind The Curtain? | The Allspark

thanks Ian … Really awesome … thanks

Pingback: これは全速力で走っちゃうよ!!トランスフォーマーロストエイジのメイキング映像。 | photoshop777

Pingback: ‘Age Of Extinction’ Was The Most Difficult ‘Transformers’ Movie To Make | Construction

Pingback: ‘Age Of Extinction’ Was The Most Difficult ‘Transformers’ Movie To Make | Essential Post

Pingback: ‘Age Of Extinction’ Was The Most Difficult ‘Transformers’ Movie To Make | MoooOovie.com

Pingback: Transformers: Age Of Extinction | Anatomy of a Movie | Dissecting a Film and all its Parts

Pingback: ‘Age Of Extinction’ Was The Most Difficult ‘Transformers’ Movie To Make | Construction

Pingback: ‘Age Of Extinction’ Was The Most Difficult ‘Transformers’ Movie To Make | Blogsfera

Pingback: 'Age Of Extinction' Was The Most Difficult 'Transformers' Movie To Make | The Usual Sources – Where You Are The Source.

Pingback: 'Age Of Extinction' Was The Most Difficult 'Transformers' Movie To Make | News

Pingback: Paris Richard Hall Jr | FXGuide Covers Transformers

Pingback: Paris Richard Hall Jr | FXGuide Transformers 4 Podcast

Pingback: Planets Of The Apes: Special | Anatomy of a Movie | Dissecting a Film and all its Parts

Pingback: Transformers: Age of Extinction | Jasmine Sumayyah Washington

Pingback: Inspirations and ideas – Animation studios