In this Part 2 of our look at LED Virtual Production stages, we look at issues around implementing in-camera VFX and some of the history leading up to its use on The Mandalorian. Link to Part 1 here.

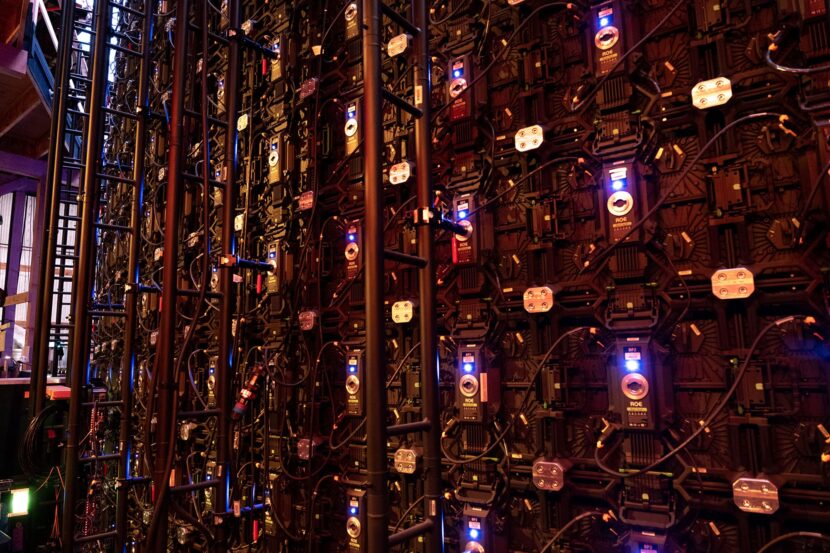

The actual LED wall on The Mandolorian both for Season 1 and 2 was provided by Fuse Technical Group. The Fuse team engineered, installed, maintained and rented the physical LED Wall to the production, headed by Fred Waldman. Interestingly, Waldman and his team were also behind the screens used in First Man and contributed to the testing and execution of Gravity (see below), Murder on the Orient Express amongst many others.

How you make an LED VP stage

Most of the technology used to get The Mandalorian up and running from Epic games perspective is now either released in the Unreal Engine or will be soon. Projects such as The Mandalorian help identify virtual production issues and once prototype software is developed to solve those issues, it invariably finds its way, in a more robust or polished way, into the main UE4 Engine. “Most of the tech in The Mandalorian is in UE4.24,” comments Andy Blondin, Senior Technical Product Designer at Epic Games. “I would say 90% is in UE4.24. The last bit of it’s going in UE4.25 which comes out very soon.” (Note Preview 1 of UE4.25 is out now). It is also worth noting that UE4.25 will have multi-frustum so two cameras can be used at the same time. In the case where the frustums overlap, one (primary) frustum would win. “Another thing is a special Python application, written by Jeff Farris, that we’re giving out to select clients. It is a kind of ‘stage manager’ tool where one can launch multiple machines to the same level, and sync them all to a specific change list. It is sort of booting systems up, at the same time to the same point,” Blondin adds.

Most of the technology used to get The Mandalorian up and running from Epic games perspective is now either released in the Unreal Engine or will be soon. Projects such as The Mandalorian help identify virtual production issues and once prototype software is developed to solve those issues, it invariably finds its way, in a more robust or polished way, into the main UE4 Engine. “Most of the tech in The Mandalorian is in UE4.24,” comments Andy Blondin, Senior Technical Product Designer at Epic Games. “I would say 90% is in UE4.24. The last bit of it’s going in UE4.25 which comes out very soon.” (Note Preview 1 of UE4.25 is out now). It is also worth noting that UE4.25 will have multi-frustum so two cameras can be used at the same time. In the case where the frustums overlap, one (primary) frustum would win. “Another thing is a special Python application, written by Jeff Farris, that we’re giving out to select clients. It is a kind of ‘stage manager’ tool where one can launch multiple machines to the same level, and sync them all to a specific change list. It is sort of booting systems up, at the same time to the same point,” Blondin adds.

The notion of a ‘stage manager’ tool is that one person should be able to run an entire stage and manage multiple machines easily in a virtual production environment, such as an LED ‘Mandalorian’ style set. Jerome Platteaux, Art Director at Epic Games, explains, “Say we need to switch to a new scene which is in the Hanger. We could go to the Switchboard, clear all the Unreal Engine, and thus the LED wall goes back to blank. Then we would simply say, ‘okay, let’s go to scene two’ and all the machines would switch to scene 2 via switchboard and open and load the correct scene (and version number). This is instead of having somebody going to each computer and individually going, open, and then…open, …open,… open, etc.”. Switchboard developed into Stage Manager in UE4 once the initial R&D was done.

Tools such as Stage Manager are not required to run an LED Stage, they just make life easier. Others such as nDisplay and Multi-user were mandatory for the use of an LED stage to be able to facilitate this next-generation of in-camera VFX. A special team at Epic worked hard with the filmmakers to make this happen, as we documented in Part 1 of this special Art of Virtual Production. fxguide sat down with the Epic Games Special Projects team to discuss how to learn how to make an LED Virtual Studio.

The Key Aspect

The key aspect of building an LED Virtual Production studio is to have a consistent synced world mapped onto a vast array of screens, such that the view is always correct from the camera. This requires both working inside a tracking volume and being able to have multiple people and machines access the one master UE4 setup. Not only must this one scene be shared but it needs to update within a fraction of a second, or the effect would lag and fail for tracking shots. What defines these new stages over previous backlit sets and projection systems is the interactive live-updating provided by the Game Engine.

PC Setup to run the VP screens

To use season 1 of The Mandalorian as an example, the large circular wall was run by four PCs in a rack that were linked up using nDisplay running at 24Hz. This render cluster needed no operators, it just ran the giant display. There were three additional PCs in the control ‘brain bar’ area, just off the set, each manned by individual operators. All 7 computers were linked in one large multi-user setting.

nDisplay

The Unreal Engine supports the usage scenario of having a scene displayed over simultaneous multiple displays through a system called nDisplay. It manages all the calculations involved in computing the viewing frustum for each screen at every frame, based on the spatial layout of the display hardware. nDisplay ensures that the content being shown on the various LED screens remained exactly in sync. While The Mandalorin used four PCs to run the LED wall, the current implementation of nDisplay in 4.25 can handle in excess of 32 nodes (PCs with NVIDIA Quadro RTX cards)

Multi-user

The Multi-User collaborative workflow is built on a client-server model, where a single server hosts any number of sessions. Each session is a separate virtual workspace that any Unreal Editor instance on the same network can connect to in order to collaborate on the same project content inside a shared environment. While inside a session workspace, each user could interact with The Mandalorian set content in any way allowable by their instance of UE4. Some user control came from using the powerful PCs, while more came from an iPad as artists walked around the LED set. If desired, as a digital prop was moved or adjusted, all the changes were synchronized immediately with all the other UE sessions, even before someone could release their mouse button, or it could just be updated on an explicit ‘save’ command.

(General purpose releases of nDisplay and Multi-user shipped in UE4.23)

Multi-user VR scouting

Multi-user could also be used to scout locations before the team is even on a virtual production stage. With Multi-user, several people on their own VR headsets can join each other in a single set and do VR scouting. This is exactly how Jon Favreau and the DP would work out shots for The Mandalorian in pre-production.

Roles on set

One of the important staffing issues is the move to having ‘post’ people on set as part of the main production crew. For many years VFX teams have supervised material for use in Post-production, but now those teams are producing VFX during Production.

In the case of The Mandalorian, three team members in the “brain bar” each had a different function but depending on the workload at any given moment they could change their focus to help. The first operator controlled the master UE4 setup. “This was the primary box and it effectively owned the whole cluster. That box would record takes, it would get the slate and it would save data,” explained Jeff Farris Epic’s Technical Lead. “One station was mainly for scene editing and a third station was for composites. That machine was hooked up to extra monitors and it got a video feed from ‘video village’,” he explains. If the team had had a green screen in use and the director wanted to see a live preview of what it would look like, then the third station would be able to do a realtime comp using the camera feed and the scene view. This could then be split out to the director’s monitor or perhaps another monitor for the cinematographer or Steadicam operator to see. This last machine was special as it had the video capture card. UE4 has Composure, a real-time compositing plugin, so temp composites can be done inside UE4.

Beyond the additional crew a production may now require onset, the environment team needs to be advanced in their scheduling, moving many roles from post-production to pre-production. While this affects the pull-down budget, a much greater volume of VFX will similarly be completed before principle photography finishes. Furthermore, post-viz is reduced as temp comps are not required for editorial. Character animation and other VFX aspects will still be done after principal photography, but the overall schedule should be shorter, all things being equal, as the shot count is reduced. In the case of the Mandalorian, post effects shots were reduced by half.

One has to think differently about producing a show with this technique. The digital sets have to have the same production schedule as the physical sets, and they have to be done with artists who really know what they’re doing in a game engine, or they’re not going to look good enough. People are so used to previs “not needing to look good” that one has to break that habit if you’re going to do in-camera VFX. For The Mandalorian, the Production Designer Andrew Jones was 100% on board with this approach because it gave him the flexibility to design sets with the best of both worlds. He could say, ‘This will be practical and this will be digital,’ and then at the same time direct and build all the things he needed for both at the same time. That way, one can get a unified vision, not a creative hand-off between departments. If something’s not working in one world or you can’t afford it, you can transfer it to the other world and keep the vision coherent. Jones really embraced the approach. Crew commented that it was, “cool to walk into a location where it feels like this massive build, but you’re standing in a holodeck surrounded by a few physical props and set pieces, while the screens make you feel like you’re in a completely different planet.”

iPad control

As the stage is designed to be interactive, mobile control is needed. Rather than drive the stage from the ‘Brain Bar’ a single operator can walk with the DP and Director and adjust props and lighting using a single iPad.

At SIGGRAPH 2019, Epic showed a Virtual Production iPad which was based on web-based REST-based API. This technology has been released inside UE4.24 . In UE4.26 it will receive an upgrade that allows people to easily make their own apps, but being web-based it will run on anything with a web browser.”

The iPad controller which was part of the Multi-user system on The Mandalorian was extremely powerful, and one can do an enormous amount with the tool. It allows for volumetric colour correction, exposure control, lighting, time day, moving props and spawn light cards to be used as light panels. “Adding a light was just hit a button: spawn the light, what shape do you want, where, how intense? And then boom, there it is. As opposed to someone having to bring in lights, run extension cords and do that traditional type of stuff” points out Epic Games Senior Producer, Richard Ugarte.

Using the Wall as light panels.

The primary use for the LED virtual set is to provide the correct digital environment and thus also provide the ‘correct’ lighting on the actor on the stage. But the ‘correct’ lighting is not what is always wanted. On a real location film set, the lighting is seldom just the natural lighting of the location. Lights, scrim, and bounce cards are always used to light an actor.

The primary use for the LED virtual set is to provide the correct digital environment and thus also provide the ‘correct’ lighting on the actor on the stage. But the ‘correct’ lighting is not what is always wanted. On a real location film set, the lighting is seldom just the natural lighting of the location. Lights, scrim, and bounce cards are always used to light an actor.

Inside an LED stage it is also possible that the environment lighting needs to be enhanced for appropriate ‘Hollywood’ lighting on the actors. On the LED stage, it is possible to add digital light cards to the UE4 world to lift or add separation to an actor or prop much as you would with real light panels or bounce cards. As long as the digital light card is outside the viewing frustum of the camera, one can do anything, with the limitation that the card will always be on the wall and cannot be brought in closer to the subject. It is also worth noting that the LED screens are seldom shot with their full brightness, so there is room for much brighter ‘digital’ light cards than the surrounding environment.

This approach was used on lighting things such as the Mandalorian’s reflective metal suit, where specific reflections could be manipulated by adjusting arbitrary shaped, reflected light cards.

In addition to using the LED wall for lighting live-action actors and sets, you can also use the DMX lighting from within the Unreal engine to drive more intense lights like Arri SkyPanels or L10s.

Screen pitch

The LED pitch refers to an LED display’s ‘pixel pitch’, which is the shortest distance from the center of one pixel to the center of the next. The ILM Mandalorian screen had a pitch of 2.84, which is significant, as we pointed out in Part 1 of our series regarding moire patterns. In reality, pitch specifications are becoming much better, such as in broadcast where it is not uncommon to work with 0.9 pixel pitch. But it is not an absolute number that determines moire. It is a ratio of pitch to distance at a particular exposure. “The team at Lux on The Mandalorian had a ratio that they felt comfortable with and I think it was always like 12 to 15 feet away from the wall at a certain T stop,” commented Blondin.

The Mandalorian, used ROE Black Pearl 2 panels, while Christie’s projectors were not used on that show, the Christie’s web site points out that to estimate the optimal viewing distance, there is a simple calculation: Optimal viewing distance (in feet) = Pixel pitch x 8*

*in meters instead of feet, the formula is pixel pitch x 2.5.

For example below is the calculation to estimate the optimal viewing distances for Christie LED display tiles, at four different pixel pitches (1.9, 2.5, 3 and 4):

Christie Velvet LED display Pixel pitch x 8 = Optimal viewing distance (Approx.)

1.9mm 1.9 x 8 = 15 feet

2.5mm 2.5 x 8 = 20 feet

3mm 3 x 8 = 24 feet

4mm 4 x 8 = 32 feet

This is somewhat affected by the LED brightness and it assumes a direct viewing angle.

Viewing Angle

The viewing angle can affect the colour or the cast from the screens. Some large panels are made in such a way that the LEDs sit in a tiny inset. “On some LED panels, there is a little bit of plastic standing around the LED,” explains Farris. This means if one looks at any panel with a grazing angle, depending on the angle to the actual LED, it can obscure the red and not the other two blue or green parts of the LED triangle. This leads to a color shift.

These color shifts depending on where you look from and yet, if one was standing under the panel and looking directly up – the image would have no hue shift. In other words, the light directly below is correct, but it photographs incorrectly if some panels are filmed at a very sharp grazing angle. As panels improve, this artifact will diminish, but on The Mandalorian, it was a minor noticeable effect. For example with the Mandalorian’s helmet, “if you put the helmet out in the middle of the set, depending on how you oriented it and the camera, you could be filming the helmet in the center of the volume but still get a slight green cast on one side of the helmet and a faint pink cast on the other, just because the ceiling was so big across,” commented Farris. For this reason, Blondin expects that many productions may end up with curved domed stages rather than the current stage design which has a cylindrical vertical structure but with a flat-top design.

Latency

Latency is critical for In-Camera VFX. The Epic team believe that a stage can be comfortably run today with about 7 to 8 frames latency. Farris comments that typically, “the camera tracking adds one to two frames, depending on the capture volume software, even up to three frames. This is before the Unreal the signal is delivered to the Unreal Engine. UE4 typically takes two to three frames due to the deferred rendering, and then the processor chain may take two or three. So the entire time from the camera moving to photons being displayed on the wall was perhaps nine frames on The Mandalorian“.

Stage Size and Light Levels

The first impulse when considering stage size is being concerned about light levels, but modern LED panels are so bright they are almost never run at full brightness. If anything, getting the screen dark enough is the issue, especially with the sensitivity of modern cameras. Additionally, as stages are made larger, it is true the panels move away but this is offset by the larger number of screens, thus the inverse law cancels out. Making a bigger stage is mainly a function of screen costs and engineering to support the roof structure. At the temp SIGGRAPH 2019 stage, the top monitors were different from the side panels due to weight. Assuming the stage needs to be clear of supports, hanging the monitor banks is the major issue with large stages.

Future enhancements

While the system clearly works very well now, the team does have more tools they are planning. For example, on a show such as The Mandalorian, all the graphics tended to be rendered in focus and the focus effects that the viewer sees comes from the actual focus of the camera. But it may be useful in some instances to have a UE4 feature for depth estimation based on the camera’s distance in the ‘real world’. Here UE4 would track the camera’s position, get that point in 3D space and then alter the depth of field on the wall’s virtual displayed graphics to reflect that viewing pyramid depth of field correctly. In any real camera and lens, there is no actual in-focus and out-of-focus hard delineating points. There is a progressively changing focus field, that we just loosely bifurcate into a binary ‘in or out’ of focus.

Background and History

The idea of an LED wall is not new, but having a completely enclosed environment with correct parallax enabling in-camera VFX has not been possible until recently. For example, companies such as Stargate Digital, under the leadership of CEO and Founder Sam Nicholson A.S.C., have been using lighting panels for car shots (reflections and outside windows) for several years, as well as virtual sets with their ThruView system.

2019:

This current LED VP technology from Epic Games was first shown publicly at SIGGRAPH in LA last year. The stage there was a box and not a curved screen that was used on The Mandalorian, but the closed demo to invited industry guests allowed a lot of filmmakers to test the approach first hand.

The demo was staged as a collaborative project with Lux Machina, Magnopus, Profile Studios, Quixel, ARRI, and Matt Workman.

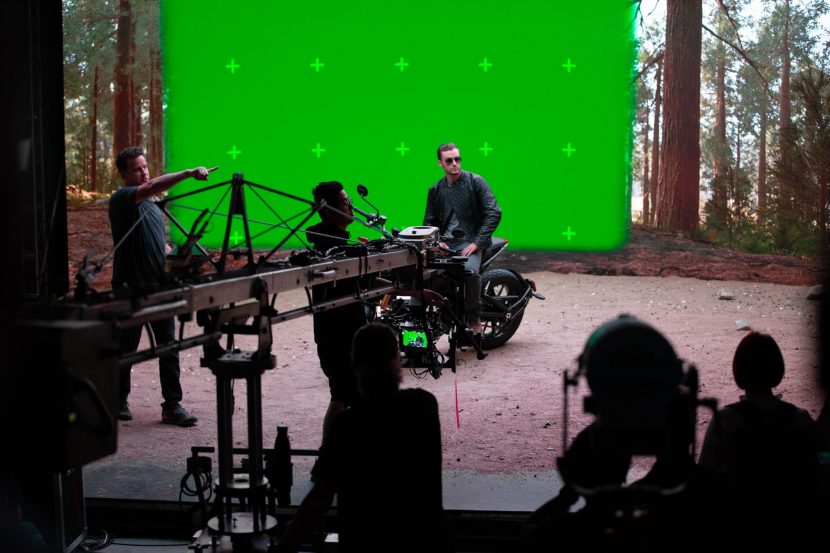

If the green screen is needed then just a dynamic patch can appear behind the actor, but the rest of the box or cube-like set still produces the correct contact lighting.

2018:

Jon Favreau was working on The Lion King when the idea for The Mandalorian series was being discussed. Naturally, he started by workshopping ideas with some of the visual effects professionals who had so expertly innovated the feature film pipeline forThe Lion King.

“When Lion King was winding down, everyone was pretty happy with the real-time filmmaking experience. Jon said ‘What could we do if we wanted to do that same thing, but with real actors?'” recalled Oscar-winning VFX supervisor Ben Grossmann. Grossmann’s Magnopus team was a key part of the SIGGRAPH concept demonstration in 2019 as Magnopus were responsible for a lot of the virtual camera implementation on The Lion King.

“Rob Legato and I did some brainstorming with him about shooting on LED walls, as an advancement of rear-screen projection going back to the 1960s. We knew the technique would need some major updates to give parallax to the physical camera. It would need to use the highest quality real-time game assets on the screen, and it would need to be a pretty big screen, in many cases going almost 360º around the actors. We figured it was just on the edge of ‘possible’,” he adds.

A small team including members of Magnopus did some proofs of concept and figured out it could work. “We knew that we’d need some major assistance, I’d been talking to David Morin at Epic, he got us hooked up with Kim Libreri, CTO of Unreal Engine and Kim jumped right on it with his team from Epic. They’d been working on real-time raytracing, and we knew that technology was ultimately going to be a path forward for the industry that would get updates as time went on, even if that feature wasn’t ready to go for season 1.”

“We saw this collaboration as an opportunity to push game engine technology beyond the state of the art, into high-end photo-realistic VFX pipelines,” said Kim Libreri, CTO, Epic Games. “Jon Favreau had the foresight and experience with the teams and technology to know that we could pull off the momentous task of bringing the creative center of gravity back on set in a direct-able and highly collaborative manner. Rendering CGI in real-time has always been the holy grail for visual effects .., We are now starting to make this a reality that will forever change the way we make films.”

As the project advanced ILM, Epic, Magnopus, and the other contributors were in a position of not knowing what was going to be possible, and Libreri credits Favreau for having a vision and for completely supporting the project from the start. ILM had earlier done a similar Star Wars test project with projectors. The ILM test on the sound stage at ILM (Presidio in San Francisco), allowed a director to walk a stage space with images correctly image projection-mapped so from their unique position in the setup, the world looked correct. Disney also had an early Imagineering project with the CAVE that again relied on projectors. The problem with projectors is that light levels, once at scale, are very difficult to get working with high enough light levels, even with complex projector lens designed for this style of special close-to-wall projection, (see below).

The special development team from Epic worked extremely hard on setting up some early camera tests to make sure that everything worked, “I can’t say enough good stuff about the work Epic did” Grossmann comments. “They sent over all their best people, and if they hadn’t jumped on it as they did, I’m pretty sure it wouldn’t have happened”. Libreri had his team of engineers coding, and in addition to Epic’s artists building assets, they wrote a lot of custom code to integrate UE4 with the LED screen hardware from Lux Machina, as well as the stage operations and motion capture volume from Profile Studios. “While they were developing all that, our team at Magnopus started blocking out and “shooting” scenes in the new (now “old”) Lion King system with Jon Favreau & Greig Frasier, just to get an advance on what everything was going to look like.”

“Because we were moving into Unreal Engine to get the visual fidelity on the screen, we started writing more advanced versions of the tools we had on The Lion King directly into Unreal Engine,” Grossmann adds. This way they were able to get improvements and upgrades as the overall UE4 engine released updates. “It also meant that those tools could be available in the future to other filmmakers, which was a thing Jon really believed in.”

The theory in these early days, well before production was underway was that the system would probably work for the shows simpler shots, but there would still be a lot of times when the actual VFX crew would need to add more complex things such as render-heavy character animation.

Jon Favreau had the idea that if a shot was showing issues, or the background wasn’t quite good enough, then the team could render in UE4, using a green halo just around the actors, tracked from the camera’s perspective. In this way, the editorial team would know what the shot was, but the VFX team would avoid having to use roto to replace the background. “That was a really cool thing to see on the screen, and it made it so that you could just switch approaches on the fly based on what was best for the end result. You could line up shots to block out a scene and say, ‘Ok, from these positions, the screen works great so let’s shoot those.’ When we get into this angle or that action, it’s not quite good enough so we can shoot a reference, but then click a button and put a green screen behind the actors and keep shooting,” explains Grossmann. ILM was keen to offer this feature in their StageCraft as they had been doing R&D on this for some time.

When the team was first spitballing the idea, everyone was “pretty freaked about the VFX budget for the show,” recalls Grossmann. “We guessed that we might get 10% of the shots in-camera”. But as the show and the technology improved, more and more of the final pixels in the show were filmed in real-time. “But a funny thing happens when you can actually see what you’re doing on set, and you start shooting to favor that technique. I think Jon said about half of the shots he thought would be VFX ended up happening in real-time on the screens, which was way past what we expected,” says Grossmann.

Other ILM Star Wars Films: Solo and Rogue One:

Both John Knoll and Rob Bredow, on Rogue One and Solo: A Star Wars Story, respectively, explored using various techniques to get in-camera VFX. Immersive environments in both cases explored the practical use of lighting display technology to blend the lines between traditional VFX and in-camera VFX. On Solo, the team used advanced projection technology to provide in-camera effects and believable lighting.

For the interior Millennium Falcon cockpit set, rear projection screens were utilized so that the actors could see and react to pre-designed animations of flying and entering hyperspace. Philip Galler and his team at Lux Machina, who had worked previously on Rogue One, joined the team to help develop the on-set giant projection system. Read about it here.

There have been other projects employing projectors or LED walls outside cockpits, for example, Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, (visual effects supervisor Paul Franklin and the team at DNeg).

Oblivion

For Tom Cruise’s floating sky tower apartment in Oblivion, to acquire the necessary backgrounds, Pixomondo’s visual effects supervisor Bjorn Mayer traveled to a Hawaiian mountains to get footage. The result was plates that were stitched together in Nuke, with some additional CG elements into a 13K wide and 2K high images running as a 20-minute clip.

This was then projected 500 foot wide by 42 feet with 21 PRG projectors on set. “We came up with a system that produced 13 HD clips, so every setup is 13 clips,” explains Mayer. “The projection is portrait, not landscape, so we had 13 of these next to each other – seamlessly playing five minutes of cloud footage. We had 10 settings. The director wanted 10 different variations based on clouds, rainy, sunny – so he had something to choose from onset. These 10 times 13 clips were uploaded to PRG and we put it on their machines and projected it onset, and moved it around.”

DOP Claudio Miranda, ASC, was able to use the projections to light his actors and produce real reflections in their eyes and have them interact with their environment. He shot at 800 ASA at T1.3-2.0 split. “Tom (Cruise) was like, ‘I love being in here, no bluescreen, I’m really in my environment.’,” says Miranda. “You walk on set and the sun’s out and the clouds are out and it’s all moving. To have 500 feet of screen at 15K resolution is pretty outstanding. Just imagine yourself in that whole thing. You’re in a glass tower up in the sky and all the glass reflections are real, all the human skin sub-surface is real. That is something that I think is so unique to this movie. It was a big install, a big commitment.” Mayer says that with so many reflective surfaces on the sky tower set, “if we had done this bluescreen we probably would still have been trying to key it!”

Of course, unlike The Mandalorian, the background was not generated in real-time, and as it was far away from the Tower, no parallax was required so simple playback worked in this instance.

It is worth noting that Lux Machina who worked so successfully on The Mandalorian also worked on Solo, Rogue One, and Oblivion.

Gravity

An advanced use of a lightbox cube was in the Oscar winning Gravity, (VFX by Framestore). The Gravity lightbox that actors were filmed in, resembled a hollow cube, standing more than 20 feet tall and 10 feet wide. The interior walls were constructed of 196 panels, each measuring approximately 2 feet by 2 feet and each holding 4,096 tiny LED lights.

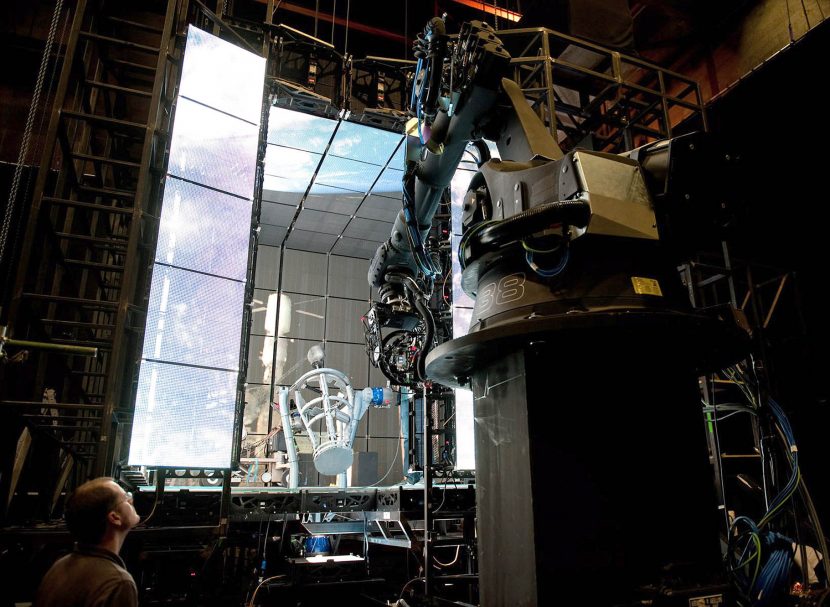

On days when the team was filming just actress only Sandra Bullock for her space floating sequences, the entire sound stage was a lightbox – with a run of rails and a robotic arm on Bot&Dolly’s IRIS rig holding an ARRI Alexa.

The lightbox consisted of a large array of LEDs – essentially like inward-facing screens of a giant television, but much much closer to the actress than today’s LED stages. It was based on the technology used at that time, which in 2012-2013 was most commonly putting images on screens behind rock bands or on screens at sports grounds. “Each pixel is made out of an LED that we could control,” explained Framestore’s Oscar-Winning VFX Supervisor Tim Webber. “There were essentially 1,800,000 individual lights that we could individually control, so that rather than moving a physical light we could just fade each individual light up and down or put different colors on different lights. So that would be how we move different lights around, not by moving anything physically but moving the image on the screens essentially.”

The LEDs were coarse and not perfectly blended, but Webber found that a lot of the time “it didn’t really matter because the light just blended and it was fine. But there were certain points where we had to put diffusion on. Those LED panels have strange behavior – they have strange spectrums of light, they change color quite dramatically depending on what angle, and it’s different on the vertical angle change to the horizontal angle change, so we had to compensate for all of that.”

To read more about Gravity see our story from 2013.

Light Stage and David Fincher

Interestingly, the Gravity team explored using Light Stage scans of the lead actors for 3D faces. The Light Stage was invented and headed by Dr Paul Debevec and the team then at USC-ICT.

“We used Light Stage to get some scans of George and Sandra,” explains Framestore’s Tim Webber. “For a few shots they are CG faces, but pretty few. Less than we had originally intended, because the other techniques we developed worked so well, and it’s actually easier to use a real face if you can, and we found ways to get it to work. Doing a CG face that is 100 percent believable and you completely buy into and doesn’t fall into the Uncanny Valley is still no easy achievement. And to do it for a whole movie would be a real challenge.” It was decided that this wasn’t the flavor for this movie.

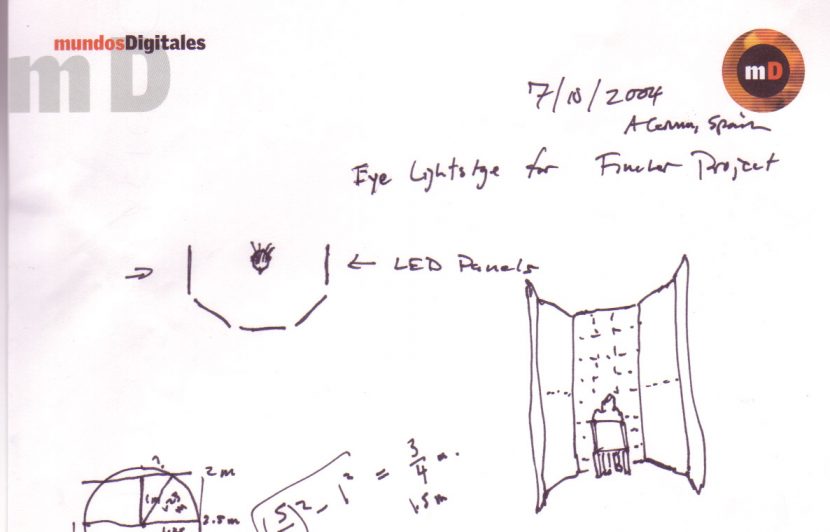

A decade earlier in 2002, the same USC ICT research team headed by Debevec had suggested a similar approach of an all-around “lighting reproduction system” that could take forms including the “walls, ceiling, and floor of a room.” Debevec thought it would be viable, having done some similar research inside the Light Stage 3. Back then, they only had the actor on a simpler rotating gantry, and the team never implemented a full robotic camera (although this was suggested) – but this did allow “the world spinning around the actor” in the Light Stage 3, by having the lights of the light stage programmed to rotate around the actor. They even explored the LED wall/cube concept briefly in partnership with Digital Domain in 2004 using Barco panels, but the project did not move forward.

The diagram above was the initial idea for the LED – DD project for David Fincher. “… It was for an early version of Benjamin Button,” explains Dr Paul Debevec. “DD had brought David Fincher by our lab and he was very interested to see if a light stage could provide matched controllable lighting on eyes. In this idea, Button’s eyes could be a live actor and the face and head could be digital. I knew we would need a higher resolution for that, and designed this setup to surround the actor with LED panels. BARCO then set up one wall of it for the test we did in September 2004, and we showed that the eye reflections were fine. DD ended up going all-CG for the Button character, but we got to help out with that process too.”

StageCraft for all

As part of the announcement made this month by Lucasfilm, ILM is also moving to make this new end-to-end virtual production solution, ‘ILM StageCraft’, available for other filmmakers, agencies, and showrunners to use worldwide.