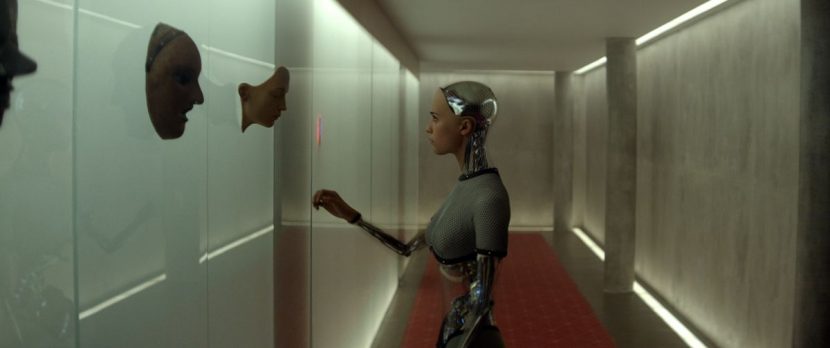

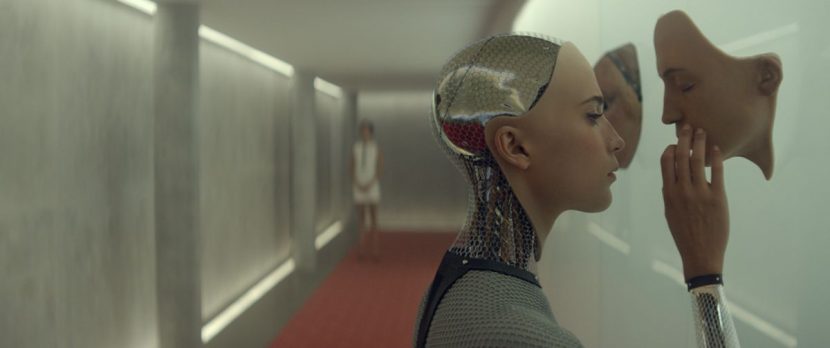

Alex Garland’s Ex Machina tells the story of a computer programmer, Caleb (Domnhall Gleeson), who spends a week with tech CEO, Nathan (Oscar Isaac). At Nathan’s house, Caleb encounters Ava (Alicia Vikander), an artificially intelligent android. Ava is imagined in the film as a cyborg with a striking humanistic appearance but also obvious translucent robotic parts – elements brought to life under the supervision of Double Negative’s Andrew Whitehurst. In this article, we find out from Whitehurst how the visual effects team set out to meticulously track live action photography featuring Vikander and other characters and then seamlessly composite Ava’s CG rendered body parts into the shots.

Designing Ava

Ava’s final look came from art department concepts and DNeg art, including depicting where real skin would end and where the CG would begin. “I was conscious that I didn’t want to push for super realistic concept paintings,” says Whitehurst. “We had to stop and then go and build it – it’s a sculpting and engineering problem – and then we did turntables. At the start of the shoot we had concepts that featured just clean metal and no textures, and then during the shoot our team would be painting up textures.”

“We made the decision to try and keep the shoulders and armpits in plate for the simple reason that rigging shoulder blades is not that much fun,” notes Whitehurst. “Similarly, we wanted to keep the hands and feet and face because that was the main method of interacting with the environment and the main method of expression. The arms and legs are full CG because we see through them, and the same with the back of the head and neck.”

Ava is clearly intended to be a robot of some kind, but Whitehurst was adamant that she not feel robotic in terms of her CG materials. “The one rule I made from the outset,” he says, “was that no-one was allowed to look at robots. You were allowed, though, to look at things like Formula One suspension or high-end bicycles. We also looked at human anatomy, of course. Ultimately she’s a machine who is supposed to move and behave exactly as a human would. All of the muscles we have in there are simplified versions of human ones, for instance.”

“Initially the back of Ava’s head and neck were not metal,” adds Whitehurst, “but that decision was made to have the character weirder to look at. One of the topics or ideas in the film is that we wanted her to look robotic. When you are presented with that visually, do I read her as a character or do I read her as a machine?”

In fact, every single muscle and bone shape in Ava was based on human reference. “They have a mechanical quality but are derived from human equivalent,” states Whitehurst. “When we designed it, they got 3D prints of it made for a scene in a lab where another version of her is being constructed – the guys making it said it was great – mechanically it all fit together and just worked!”

Shooting Ava

Much of Ex Machina takes place inside Nathan’s house – an isolated building in the mountains filled with glass-lined walls. “The set was really like an enclosed glass box,” describes Whitehurst. “That meant the camera was either inside or outside, and there’s nowhere to hide really, because it meant later on we had to body track things three or four times because the reflections are all different from lens and mirror distortion.”

That location challenge was exacerbated by the style of the film – Ex Machina is not intended to be an action adventure, but a more cerebral and intimate piece. “Because the whole film is about human consciousness and what it means to be human and what it means to be conscious,” outlines Whitehurst, “it’s very conversation-driven, almost exclusively. In order to get that relationship, you have to have an actor talking to another actor – they have to feed off each other.”

The result was that, although significant digital work would be carried out by the visual effects team, motion capture was not an option. The actors were always in the plates. For each take, then, a clean plate was acquired, and later extensive body tracking – including for shots up to 1600 frames – would be necessary.

More from on-set.Production filmed on the Sony F-65 with anamorphic lenses, which would ultimately make for challenging plate tracking. “We did have one or two witness cams,” notes Whitehurst. “The sets were all closed and not that massive, so the opportunities for placing witness cameras were limited. We always tried to have one and if we could get a second one in there we did. We had to paint out witness cams for some shots since it was sometimes just easier to do that and use it for body tracking.”

On set, Vikander wore a gray wetsuit material costume covering most of her body. When visual effects replaced a section of the actor, the remaining parts were still the wetsuit material. Each setup involved an IBL take. “The way the sets were built actually really let lent themselves for IBLs,” notes Whitehurst. “Plus at DNeg we have physically based shading pipeline and it really meant down the pipe that our lighting just worked.”

Building Ava

Design and texturing of an Ava model continued at DNeg during principal photography, after which it was clear the rig had to be ‘astonishingly flexible’. “This was because of the different distortions that the anamorphic lens applies,” explains Whitehurst. “If she’s not perfectly in focus, the lens warps the space, so we have to shift her to counteract that. It’s not just a question of de-lensing it to try and get the lines straight – you have issues, as soon as it goes out of focus, it’s still actually distorting things back and forwards of the focal point.”

To ensure the CG elements would perfectly match to the live action photography, Vikander was initially photobooth scanned in pre-production so her equivalent CG model could be built. Once the final costume was ready on set, the actress was scanned again and the model refined.

Watch a clip from the film.A key aspect of Ava’s appearance was the mix of hard metal and then softer outer skin. The visual effects team also added ‘ribbons’ of plastic visible on the inside of Ava’s translucent shell areas, which came from experiments made during the concept art phase. “There was this lovely air of mystery you got from playing with the brushstrokes which meant that as soon as you build something for real, you can lose. So we thought, ‘How could we add that sense of slightly confusing mystery back to her?’ What we did was add these translucent ribbons that run up and down the torso that just have that little bit of refraction on them so it just breaks things up.”

Ava’s inner mechanical parts, representing muscles to some degree, were constantly moving as she did, as Whitehurst explains: “They were all built into a rig where all of the muscles would fire correctly, and then we had various organs and gyroscopes that would just spin throughout. We ended up with a gold mesh based on air-actuated robot modules we found and then we wrapped a spiral of metal around each muscle because that helped read the contraction of the muscle as it’s moving. It’s almost subconscious in the end.”

The mechanical parts and ribbons were rendered via DNeg’s physically plausible rendering pipeline (which uses RenderMan). “Physically plausible gives you that photographic quality that you can’t get any other way,” says Whitehurst. “You can get beautiful renderings not using this approach, but they have a painted quality – they don’t feel as photographic – especially when you’re dealing with very known materials.”

Those known materials were replicated with shaders for things such as aluminum, chrome, silver and steel. “Fundamentally,” notes Whitehurst, “if the material’s correct and it doesn’t look right, then you’ve got the lighting wrong. We tested it in all the lighting environments we knew she was going to be in, and we tweaked some level of displacement on Ava’s body mesh on wider shots because you didn’t read it there.”

Having anticipated early the challenges of incorporating Ava’s CG elements into the shots, Whitehurst says that compositing was still a tough and brute-force challenge. Lens distortion from the anamorphics proved most difficult, as did adding in refraction through the see-through aspects of Ava. “You get all that anamorphic goodness happening around the edges,” says Whitehurst of the lens choices. “Which also meant it was one of the hardest body tracking jobs we’ve ever done. The shots are long, it’s performance-based and so we have to absolutely capture what she’s doing.”

Loved the movie. Very curious to know the reasoning behind the use of anamorphic lenses. Is it purely just the look of the lenses and what they give you in terms of beautiful distortions, bokeh and flares and so forth? There seem to be quite a few cameras and non-anamorphic lenses that have remarkable image quality, so based on the difficulty that the ana lenses added to post, what did they bring to the table that wouldn’t have been possible to add in later as a post effect? Was testing done with various lenses to determine what gave the director the look he wanted and they just figured that those lenses gave them the best look possible? Hats off to everyone involved. Looking forward to watching it again.

Thanks for your comment, Jonathan. American Cinematographer has more info on the lens choices: http://www.theasc.com/ac_magazine/May2015/current.php And there’s also a podcast interview with the DOP Rob Hardy here: http://gocreativeshow.com/the-cinematography-of-ex-machina-with-rob-hardy-bcs-gcs061/

Ian

Fascinating. Thank you.