The Ambassadors in Amsterdam have just finished work on a beautiful non-profit spot for the World Wildlife Fund. Their R&D team ‘The LAB’ made an innovative tracking tool for precise on-the-set object and camera tracking. They tracked a supermodel’s body using infrared tracking markers in a dual Phantom camera rig.

Nature is Us was created by advertising agency Selmore for WWF, produced by Caviar Amsterdam and directed by Bram van Alphen. Before the project was even green lit, the agency approached Ambassadors with the technical problem of how to produce a spot like this. The Ambassadors have a special division set up permanently to tackle problems just like this called The LAB. The LAB set to work thinking about how to get a highly accurate track on the skin of a model – shot in slow motion. A traditional approach would be to cover the actress or model in tracking markers, but this then poses not only the problem of tracking but also dot removal. It occurred to the team that infrared markers would be an ideal solution: if only they could solve how to film them?

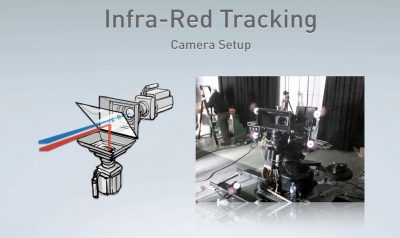

The cinematography was in the hands of Carli Hermes, who decided to shoot on the Phantom high speed camera, or more precisely, The LAB team came up with a brilliant technique of shooting on two Phantom cameras in a stereo rig – but with no stereo separation. Instead, the cameras were set up to perfectly align with no inter-occular difference or offset. The only difference between the two cameras was that one was shooting normal high speed while the other was shooting infrared. The second special sync’d Phantom could see the otherwise invisible markers on the naked body of supermodel and Victoria’s Secret Angel Doutzen Kroes. With the highly accurate skin object and camera tracking provided by the markers, the computer graphics team at the The Ambassadors then added CG plants and vegetation growing over the model’s naked body as she spins in slow motion.

How do you shoot infrared markers?

The problem is more complex than it might first appear. Most cameras have filters specifically designed to cut out infrared light, which is invisible to the human eye. Secondly, infrared lights exist, but for this to work the team would need to find non-toxic paint or ink. The next problem is that infrared cameras such as a 5D MkII modified for infrared ONLY produce an effectively black and white infrared image. For the camera to work, nearly all visible light is filtered out, so just an infrared image would be no use, since the whole point was to have a clean pass (with invisible markers) and a perfectly matching version with loads of markers. If this had been a miniature shoot then the problem would have been easy. Multiple passes would have allowed marker and non-marker passes, but a live person in motion would never be a repeatable option. Finally, the camera would be skimming the surface of her body with shallow depth of field, a problem normally for tracking markers, as multiple good tracks are needed simultaneously and a shallow depth of field would render most tracking markers too quickly unusable.

The steps

The ink

This was the first stepping off point – the team needed to know if there was a non-toxic ink that would work. “We started investigating and asking is there a type of ink that is transparent but is visible in infrared light, and it turned out that there is, and it does exist,” explains Diederik Veelo, technical producer on the spot and owner of The Ambassadors LAB. They then moved on to the rig problem. “That is something we do at The Ambassadors LAB, which is like an innovation group. We try and come up with smart ideas like this to solve problems in post-production.”

The rig

First the team settled on a stereo rig with no stereo offsets. This would allow two cameras to film the action – one filming visible light – the other filming the invisible infrared. While this would work for almost all the shots, even this solution would not be perfect. The super extremely closeup of the opening eye shot would still prove too extreme to allow a large stereo rig to get close enough due to the mirrors, but not withstanding that one shot, the rig solved the dual recording problem.

The cameras

The solution for the camera was to use a non-standard Phantom camera. Vision Research who make the Phantom comes from a pure research community and has many cameras beyond the cine cameras normally used on spots like this. The director really wanted to shoot high speed, so the Phantom was clearly one of several possible choices, but the real key was being able to use a non-standard cine high speed camera. “We wanted as perfect a match between the infrared camera and the normal camera and Phantom builds several technical cameras – one of which is a black and white camera with a very good response on the infrared spectrum,” Veelo says.

But key was that this camera also used the same sensor size (in diagonal physical size) as a high quality normal image camera. This was key as it meant that both cameras could have exactly matching PL mount lenses, for both infrared and normal action, and both cameras could be precisely synced. “The camera were pulse locked, so it is not code locked,” adds Veelo, “but pulse locked to expose each frame exactly.” Actually the pixel count resolution was different, but as the infrared just needed to provide camera movement and object tracking data, so long as the sensors where the same size, shot with the same lenses, the actual resolution was irrelevant, since no-one would see or use the infrared footage past the tracking stage of post-production.

The infrared camera was light blocked with a 780 nanometer filter, allowing only the infrared to pass through. The mirror rig’s actual glass did not affect the process. Of course, the lights and ink had very narrow response curves so if the glass had adversely filtered the infraredm the process would have failed. The team did extensive testing before heading on set for the first time. Actually, the team ended up with several inks on set, their first choice did not work in the first camera test as the camera’s specific 900nm response curve did not line up with the very specific frequencies of the infrared lights and the narrow response/emitting curve of their first ink. “The peak of the infrared curve was too high up initially,” recalls Veelo. “Fortunately we had several types of ink we were able to try out and at the end of the day we had a great solution.”

In the end the process worked so well, says Veelo, “that the camera lined up within two pixels and that was enough for us to do it and of course fix it in post.”

Watch The Ambassador’s making of for the WWF spot.On set

Applying tracking markers is normally tricky to make sure enough are visible to the camera at any one point in the shot, something every on-set supervisor knows only too well. But it is much harder to check that when the tracking dots are all invisible to your eye. “In fact I could not see what I was doing when I was applying them,” laughs Veelo as he recalls on-set preparations. “If you look carefully you can see there are a few that are (applied) close together as I was putting them on blind.” To solve the problem the team had an on-set second camera feed showing the infrared capture. Thus, on one screen was the hero color shot of the model’s back, and on the other was a black and white version with a mesh of dots only visible on that screen.

Tricks

“This project had all three major tracking problems in it – depth of field, extreme lighting and difficult retouch.”

“This project had all three major tracking problems in it – depth of field, extreme lighting and difficult retouch,” points out Veelo. Low light and shallow depth of field was always going to hamper successful tracking, but with this approach the light levels and thus f-stop of the infrared was completely independent of the low light / beauty lighting. High speed photography always requires special lighting considerations, as high speed means naturally shorter exposure, but the director wanted a wide open f-stop anyway for creative reasons. But as the second camera was being lit with its own special infrared lights, the team could flood the set with infrared light, bringing the levels way up, allowing the second camera to stop down and provide much more depth of field for the infrared image than the normal image. Areas of the model’s body that were completely defocused in the live action were still razor sharp on the infrared screen. “This was something I had not initially realized,” says Veelo, “but we could increase the infrared lighting without affecting the normal lighting on set.”

Post-production

One huge obvious example was that in post-production, once the 3D was combined the live action plate, there was no dot removal, roto fixes or touch up needed.

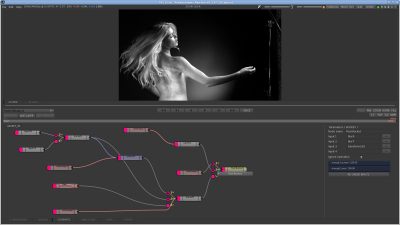

But The Ambassadors still had more tricks in their LAB. The team has developed their own software called Realism which is an in-house pre-final composite tool. The tool developed independently and well before this WWF spot sits between the Maya 3D pipeline and the team’s multiple Flame suites.

Using Realism, the team is able to render images from Maya and have the node based Realism tool automatically pre-comp the CGI with the live action. The tool allows cutting edge techniques such as deep composting to be used, while also providing a low cost prep station for hold out matte generation and testing. Realism allowed the CG artist to see their work in context as they developed the detailed plants and foliage that delicately grows over the model in the spot.

“Before Realism the 3D artists would need to wait on the Flame artist to load up the imagery,” notes Veelo, “composite it and know what was working or not. Now they can see that immediately. For example, Realism can now set up a node based composite and the 3D artist can render straight into that composite on a screen right beside them on their desk. They can render one frame, as it were, in Maya and simultaneously it is rendered into the composite.” This proved to be very important in the project as there were shots with many many layers of plants, and most of those plants were animated and rendered as separate elements. By using Realism, when say a leaf or individual plant was being animated and rendered the artist saw that immediately in the middle of all the other live action and plant layers, each artist seeing all the shot, at any time.

Unlike say Flare from Autodesk, Realism is closer to Maya in the pipeline and can use deep data. “You can have the whole Maya scene in Realism if you want,” says Veelo, “but it would of course be a lot of data.” Veelo points out “a few years ago we realized that as a post-production company you need to innovate and develop your own tools, otherwise the small two people companies will catch up to you.”

While The Ambassadors have no immediate plans to sell the tool, it exists as a fairly polished piece of software, available to all the different divisions of the company or group. In reality The Ambassadors is actually four companies split over three whole floors in Amsterdam:

“We did think about developing a three camera rig!”

On the WWF spot, there was pre-grading done in Flame, with final grading was done in Lustre by Brian Krijgsman, one of two senior colorists on staff. Krijgsman has previously worked in London and is well known and highly respected.The project has just gone to air and the team got the first exploratory phone call from the agency in September of 2011. Not counting the style and look development, the final 3D animation took about a month to animate. While the team got great tracking markers, looking forward the team would also love some way to also get depth information. We put it to the team that it is ironic that with a stereo rig shooting on set, they got no stereo deep information: “We did think about developing a THREE camera rig!,” they joked.

I’ve been playing around with this very same idea. Since modern Digital Cinema camera like the red have been able to capture more and more into the non visible infrared spectrum. Its pretty ingenious to capture it with two cameras on a stereo rig with zero offset.

Bi

Brillant*

It is great isnt it? Really clever. I love these guys – really clever and super nice guys to talk to.

great idea. I could see this working nicely in a stop motion environment, since it’s so controlled. Beats the previous idea of UV blacklights and UV paint, which seemed to be to tall of an order for the on-set folks because not all shots employ the req’d DMC controller.

I wonder if there’d be an easy way to “ka-chink!” an infrared filter into place in front of the camera during the dragon capture process so this is “just another pass…” hmmm, will have to source some oversize filters and employ a little robotics! thanks for the idea!

I heard the PhDOD podcast and I was reading the article, and I couldn’t for the life of me understand how they had set up two cameras to shoot at the same time form the exact same spot. It wasn’t until I saw the graphic with the schematic of the rig that I got it and thought, what cleverness.

Really amazing solution.

Who manufactures the ink? I’ve been searching for some to use in a real time video performance.