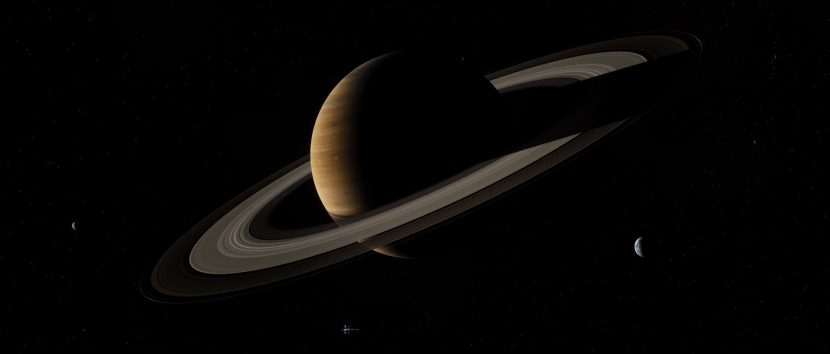

Ad Astra by director James Gray (Lost City of Z) tells the story of a man who seeks to both save the world and resolve issues with his father, in an epic journey that travels 2.7 billion miles to the second most outer planet in our solar system.

The director is quoted in early 2016 when production started, as stating that he wanted to feature ‘the most realistic depiction of space travel that’s been put in a movie’. While the plot may have certain breaks with realism, the visual style of the film and especially the visual effects, all reflect this desire for a considered visual authenticity. The issue with any space film is being able to show something accurately when the actual reality of such deep space cinematography would make storytelling visually difficult. For example, if one was to film at Neptune, there would be very little light compared to filming on the moon, as our sun would appear as little more like a bright star. However, the audience’s perception of space is based on real footage, all filmed much closer to the sun and with enormous bounce light from the earth itself. As the film is not a documentary, Ad Astra seeks to provide cinematic realism seen through the lens of the audience’s familiarity with mainly orbital and some luna real-world photography. Ad Astra very successfully provides stunning visuals that seem more than plausible while being heavily crafted to support the narrative.

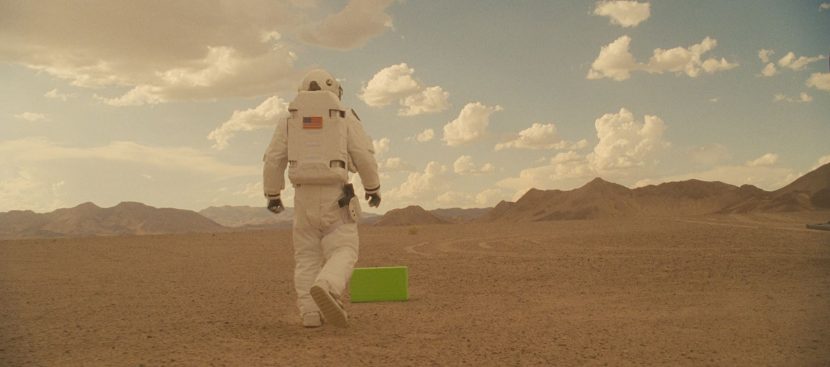

The film deployed many interesting film making approaches including filming the Luna chase sequence in Death Valley on a specially built rig that filmed on dual cameras. Oscar-nominated cinematographer Hoyte van Hoyte (Dunkirk), was the DOP and he came up with an ingenious approach to simulating lunar photography. In addition to shooting over cranked (partial slow motion) to give a reduced gravity feel to the motion, they built a unique rig to film the lunar vehicles ‘pirate’ attack. One camera was shooting traditional imagery and the other was an Arri Alexa Infrared camera. Thus the dual footage had both the traditional plate photography and a version filmed simultaneously with an infrared black sky (due to the lack of heat being transmitted from the sky, not registering on the infra-red sensor). With the exception of this sequence, van Hoytema shot Ad Astra primarily on 35mm film.

MPC was one of the several companies that the production deployed to depict this journey into darkness. A journey that echos Francis Ford Coppola’s masterpiece, Apocalypse Now. Other visual effects companies on the film included (in no order) Mr X, Weta Digital (the ‘Space-Ape’ scene), Brainstorm Digital, ILM (who initially sketched out the VFX approach of the film), Atomic Fiction, Soho VFX, Branch VFX, Legend VFX, Lola VFX, Vitality VFX and Method Studios, amongst others.

MPC was tasked with most of the rocket launches and many of the spacecraft sequences. In the film, our Solar System is struck by mysterious power surges which threaten all life. After nearly dying from an incident caused by a surge, Major Roy McBride, (Brad Pitt) flies to the moon, on route to Mars where he forces his way onto a ship being sent to Neptune. The mission is to stop the Nepture based ‘Lima Project’ and perhaps kill Brad Pitt’s on-screen father, astronaut H. Clifford McBride (Tommy Lee Jones).

MPC’s Compositing Supervisor on the film was Eric Andrusyszyn. MPC did close to 200 shots for the film. “We did the majority of our work revolved around the landing and taking off from various locations such as the moon”, he comments. “MPC did the taking off from Earth, landing on Mars, some of the Rover stuff, a lot of the space travel and a big chunk of the Neptune rings section when Brad Pitt is outside of the Lima station”. Guillaume Rocheron and Christopher Downs were the MPC visual effects supervisors. Sheldon Smith and Elizabeth Willaman were the Visual Effects Production Supervisors. With Boyd Shermis and Bradley Parker also providing Visual Effects On Set Supervisor. Halon did the previz and post-viz for the film.

Andrusyszyn reinforced the issue of cinematic realism when recalling that “the director and the production had a very specific idea of what they wanted. They wanted something that was very much grounded in reality. And you can see that completely through the aesthetics of the entire movie from the ship designs to the lunar base to pretty much everything that was created for the movie”.

For the earth rocket take-offs, MPC had a large variety of source imagery to reference. This ranged from the Luna Apollo program to the Space Shuttle, and more recently, the efforts of programs such as SpaceX.

The landings on the moon and Mars referenced the most recent efforts to have reusable rockets land on Earth in the real-world space industry. The sequences also referenced the familiar footage of the lunar landings. It is worth noting that the actual lunar landings, on a modern timeline, are closer to the invention of barbwire, than they are to the modern-day in time, thus it was critical to not just rely on Apollo footage for Ad Astra’s near future imagery of the moon landing.

For much of the film’s visual effects, the director sort to film whatever the production could at real exterior locations rather than filming actors in green screen studios.

Near the end of the film, Roy McBride ‘jumps’ to re-connect with his ship orbiting Neptune, and in heavy CG sequences such as this, the production still tried to film Brad Pitt on wires rather than just use digital doubles. MPC was able to create a good digi double of Brad Pitt, but they tried to use it as little as possible and there’s actually a fair amount of just live-action wire work composited into CG backgrounds, especially in the third final act of the film.

In addition to the Earth launch, MPC had to create rocket takeoffs from environments where there is no reference, such as Mars and the moon. This presented a set of unique challenges as there are greatly different effects of gravity and a lack of atmosphere in these locations. These are two aspects which can be normally used by a visual effects artist to denote scale and size. “We had to deal with how to make sure that we maintained a sense of scale in these environments,” comments Andrusyszyn. “We had to work on ways to sell the scale of the rockets, and so it was all about figuring out ways to get kick up material and stuff like that from the thrusters and trying to figure out how those elements would play in the different atmospheres”. Normally things falling on earth inform a viewer about scale, especially when combined with atmospheric distance clues. For example, on earth, large objects far away move slowly and are desaturated or hazy, but this is just not the case on Mars or the moon.

Much of the subtle visual clues to the audience came from the compositing process. The MPC animation team rendered multiple passes and the comp team then used a variety of techniques to sell the shots. Techniques such as optical lens flares (see above) and especially adjusting the specularity. “We really concentrated on the specular highlights in the final image, in trying to give the proper scale, the spec highlights actually made the ship feel the size that it should be”, Andrusyszyn explains. Outside of the framing and lens choices, the glare and blooming of the highlights greatly enhanced the MPC shots. “When I first approached the movie, I did a lot of research, I went to like websites like NASA. I looked at a lot of old footage from the moon landing and they captured a sort of ringing around the specular highlights,.. and that’s actually something we played with a lot – that red, grainy, sort of bloom around the highlights” he adds.

Andrusyszyn noted that the filmmakers decided to shoot with little use of a blue screen, ” they shot Brad a lot over a dark background rather than over a space background or blue screen. It was normally just very dark with very specific lighting to kind of simulate a single point Sun directional source”.

Brad Pitt was shot sometimes with, and sometimes without, a visor on the spacesuit, leading to subtle compositing to add the visor and not obscure his performance.

MPC created the animation in Maya and Houdini and the compositing was done in Nuke. MPC uses various tools, and they “use a deep pipeline. While I can’t say for certain, I think MPC uses Deep probably more than most other studios in Nuke”, speculates Andrusyszyn. “The lighting always comes to us with specific lights broken out in different ways, so, so the comp team can manipulate them in Nuke. We get all the CG elements so that, for example, we take down a key light on an element or increase the top-down light all during the comp”. Combined with the deep pipeline this gave the comp team a lot of control of the footage.

Andrusyszyn concludes by commenting that “it was great working with the production and this director, …when we started, they asked us to look at certain shots and the Director would reference, the look and visual qualities of movies such as 2001, A Space Odyssey, Gravity, Interstellar, – and with reference to these movies in general, the director wanted a ‘tangible’ product. Even though it’s is all future-based technologies, going places that we’ve never been before, everything had to feel like something that could exist in this world”.

Andrusyszyn concludes by commenting that “it was great working with the production and this director, …when we started, they asked us to look at certain shots and the Director would reference, the look and visual qualities of movies such as 2001, A Space Odyssey, Gravity, Interstellar, – and with reference to these movies in general, the director wanted a ‘tangible’ product. Even though it’s is all future-based technologies, going places that we’ve never been before, everything had to feel like something that could exist in this world”.