Digital Domain (DD) has an outstanding reputation for the integration of live action and computer graphics. From films such as Apollo 13 to The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, and more recently on Transformers: Dark of the Moon, DD have proven they can combine live action and digital almost better than anyone in the industry. So we thought we would use Real Steel to learn from the best and explore some of the tricks and techniques of integrating CGI and live action.

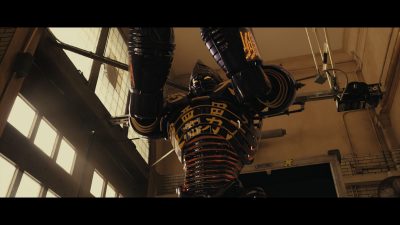

Real Steel is a gritty, white knuckle story, set in the near future, where robot boxing is the world’s top sport, and a struggling promoter’s son feels he’s found a champion in a discarded robot. During the robot’s hopeful rise to the top, the former boxer Charlie Kenton (Hugh Jackman) re-discovers he has an 11-year-old son, Max (Dakota Goyo), and together they take their robot Atom to a Rocky-esque showdown.

Real Steel is a gritty, white knuckle story, set in the near future, where robot boxing is the world’s top sport, and a struggling promoter’s son feels he’s found a champion in a discarded robot. During the robot’s hopeful rise to the top, the former boxer Charlie Kenton (Hugh Jackman) re-discovers he has an 11-year-old son, Max (Dakota Goyo), and together they take their robot Atom to a Rocky-esque showdown.

To achieve this heartwarming story of bare metal fist fighting, the filmmakers turned to Legacy Effects for practical robots and to Digital Domain, and DD visual effects supervisor Erik Nash, to create the CG robots.

– Watch a DD breakdown of the Crash Palace fight, courtesy of our media partners at The Daily.

I, Robot vs Real Steel

Digital Domain is not new to fighting robots.

One interesting aspect of this film is to compare it to I, Robot from 2004, a film that Digital Domain and Erik Nash worked on (along with Weta Digital). We spoke to Erik Nash about the similarities and differences between the two films.

A primary difference between the films was the capture medium. I, Robot was shot on 35mm film while Real Steel was captured digitally and tapelessly with the Codex coupled with Sony F35 cameras.

For the more complex fight sequences, the high quality digital capture allowed for a real time in-viewfinder preview of the pre-choreographed fight action (more on this below).

I, Robot had quite a lot of virtual sets and thus a lot of greenscreen. There was very little greenscreen used in Real Steel compared to I, Robot. When it was used, it was just a low eight foot band of green to isolate the head and shoulders of the last row of extras in the stadium shots. This produced effectively a band of green around the ring, just behind the extras.

(More on the stadium crowds below)

How to produce great CGI / live action integration

Stage 1: On-set passes

For any complex high quality live action / CGI integration, there are key tasks to be done on set, beyond either camera tracking or camera motion capture. To get accurate lighting it is vital to sample the light on set both for reference and more complex global illumination/HDR solutions.

Digital Domain used similar on-set passes when filming with main unit as they had in I,Robot, but there were some real advances since 2004.

On I, Robot, the hero robot Sonny and the robots in the film were fully CGI, the production developed a system to capture the on-set lighting reference. A special fisheye digital still camera was built into a robotic pan-and-tilt head to capture four fish-eye image positions. Multiple exposures from an automated rig produced a high dynamic range (HDR) map, which was used as a starting point for lighting and reflection maps.

Real ‘robots’ were used for many final shots on Real Steel, and these highly detailed props by Legacy Effects also provided excellent lighting and texturing reference for each setup they were used.

On I, Robot, each shot containing Sonny required the following elements to be shot:

• a rehearsal with the proxy standing in for the robot;

• the actors with the proxy;

• the actors without the proxy (DD expected to use this – but rarely did);

• a clean plate;

• a 2m reference robot for lighting;

• a chrome ball and 18 % grey ball; and

• an automated HDR pass.

On Real Steel – some seven years later – a standard shot with Atom involved a somewhat different approach:

• a rehearsal with the proxy standing in for the robot was still done;

• the actors performed the scene with the proxy (this time DD accepted that the proxy would probably need to be painted out);

• chrome and gray balls were no longer done;

• a clean plate was done but sometimes not the whole take, or no clean plate was done at all (in say a tracking shot)

• in terms of HDR passes, the difference with Real Steelwas that the HDR was simpler. There was no robotic HDR capture tiling, it was done manually. “The process is more manual but the cameras are faster,” explains Nash, “plus the HDRs were more per location or setup rather than per shot, and that one main setup would apply to all the shots at that location.”

In the long tracking shot of Atom shadow boxing with Hugh Jackman’s Charlie Kenton at the motel, there was, for example, no clean plate shot. On set it was decided that as there was depth and separation, plus the background was fairly static – bits from other parts of the take could be used to patch out the proxy stand-in. “As soon as Shawn had the take he liked, we run in and do the HDR,” says Nash.

Stage 2: Complex and dynamic HDRs

Between I,Robot and Real Steel, DD also worked on Benjamin Button, which pioneered dynamic HDRs that were not single HDRs taken at one point but a set of HDRs that allowed for the lighting to change as the digital asset moved through the wider space. This was Oscar-winning work and DD used it again on Real Steel.

For example, in the shot at the start of the film when the Ambush robot walks from the back of the truck out to the lift gate, there were two HDRs (one at the back and one at the lift gate). These two were then mapped onto the various shapes as dummy surveyed geometry of the inside the truck. This meant that “cabinets, windows and all the different surfaces in the truck are lighting the robot based on their proximity to the robot and not just all these HDR values mapped on the inside of a sphere,” says Nash, “so as the robot moves through the truck and moves through the pools of light through the window, there is an accurate spacial relationship between the robot and the light sources that are lighting it.”

“There were often three if not four HDRs taken along his path,” continues Nash, “for the changes in the lighting conditions. That was a first for any movie I worked on, typically an HDR creates an environmental sphere (ed: with a spherical mapping with an equal distance from the center to all points), which has all the lighting information in it but it has no distance information in it.”

Stage 3: Contacts and interactions

To sell a CGI / live action integration you need to move beyond just contact lighting and correct lighting models to real interaction between the CGI character and the subtle props and items of the set. Here the Ambush scene above proved much more difficult than anyone could have imagined.

Unfortunately in the back of the truck, Ambush has to push through hanging pots and wires to get to the lift gate. “That shot was a bear!,” jokes Nash. Legacy Effects had made a set of shoulder pads, leg and arm extensions to build up the stunt performer to have him move through the clutter accurately. Unfortunately, the props sort of “jostled” him about, and the director felt that the props were affecting him too much, which meant the animation that was derived from the stunt actors performance would be incorrect.

Thus, the robot walks through the clutter more directly and less affected by it bumping and smashing into it, but of course once the CGI robot moved through the space differently, the props no longer moved correctly and in sync with where he was, so DD had to remove the clutter and then re-animate new matching digital props to correctly bounce off Ambush and of course swing aside the way they would if a solid giant metal robot was moving through the space and not a stunt performer with shoulder pads and stilts.

You can hear Erik Nash talk about this process in even more depth in this week’s fxpodcast, where he discusses Real Steel and I, Robot with fxguide’s Mike Seymour.

Stage 4: Staging and framing

Erik Nash’s team produced and worked with a number of solutions to approach the framing and staging of the shots, but perhaps the most impressive was the on-set work to stage the hero fights in the ring.

The camera when shooting in the ring operated in a large capture volume that was recording and triangulating the real camera’s position and orientation. This provided a big difference when it came to staging the robots fighting in the ring. “We leveraged a lot of the technology from Avatar,” says Nash. It should be noted that the capture space was provided by Giant Studios who were key in Avatar’s virtual production. “Everywhere there was boxing, [Giant] would go in several days ahead and build a capture space. It was not as dense as you would need for normal motion capture as it was just the camera.”

The composited view on set of the ring and the robots for the Director and DOP.The F35 image was sent wirelessly to a base station that combined the information from the capture space with pre-choreographed fight action, based on motion capture done by the second unit. The base station then rendered this from the virtual camera it had calculated to match the live action camera and composite it with the live action, all in real time. This footage was then re-transmitted back to the F35 camera. So while the lens filmed an empty ring, the viewfinder of the same camera showed the camera or Steadicam operator the robots fighting away.

In scenes where Atom needs to take his movements from Hugh Jackman as Charlie Kenton, it was important for the camera person to frame the robot in the foreground, while keeping Jackman’s Kenton correctly framed in the background. The process was called Simul-Cam.

None of this live interaction was available seven years ago. For I, Robot, there was no live, on-set, previs, which in turn made framing shots for director Alex Proyas much more difficult. Yet in that earlier film there was very much a similar problem of framing for CG robot fights with key live action actor framing issues, as director Shawn Levy faced with Real Steel. Levy benefited greatly from being able to design the actual fights based on motion capture with coaches such as boxing legend Sugar Ray Leonard, but film them in the real location with the actors, props and of course capture the virtual camera in sync with filming the master live action plates.

There was no need to later try and do a traditional 3D camera track, as the camera tracking was provided already by the capture volume. Furthermore, as the camera volume only needed to capture the real rigid body camera, the on-set motion capture was relatively easy and did not slow down the filmmakers. This speed benefit followed to post production as the metadata was carried through to post (see below) and most importantly the effects team had both a rough pre-comped reference and the director had the shot he wanted and required vastly less re-framing and re-building of shot framing. “These served as first generation temps for the visual effects shots,” comments Nash.

One key limitation is the lag between the camera operator moving and seeing that move in the viewfinder. While the real time render was very good for even the editor to cut to in offline, its quality had to be balanced with lag time. “There is a discernible latency of two to three frames,” notes Nash. “It is on the ragged edge of being unacceptable, and it took a little adjustment on Dave’s (Emmerichs) part to get used to it, but for all intents and purposes it was small enough to not affect his operating.”

Nash adds: “Get past the geek factor and how cool it is to see the robots through the camera (on set), for me it is what it gives to the filmmaker. The biggest benefit for me was that it allows Shawn, Mauro and Dave Emmerichs the camera operator to shoot the robots boxing – the way they would shoot humans boxing. It is completely interactive. When Dave Emmerichs is standing in the ring with the Steadicam he’s looking at robots, he’s reacting to what the robots are doing and he’s doing it in real space in real time and I think it shows in the camera work of the fighting.”

Stage 5: A seamless, tight acquisition pipeline

Most of the principal photography was shot with four Sony F35 cameras. The cameras were tethered via fiber cabling to two Codex Digital Labs, so that all four could be recorded simultaneously. The Codex Digital Labs were located in a truck off set that served as a mobile lab for the production. (This workflow was employed, in part, because production was using Simul-Cam to overlay CG elements and so the cameras needed to operate in sync.) Codex OnBoard Recorders were used for scenes shot run-and-gun.

The movie was filmed uncompressed HD 4:4:4 RGB S-Log 10-bit. The Sony F35s only output 1920×1080, and not in RAW format. (The Codex can record RAW – for example from the Alexa – but the F35s do not support RAW). The production also needs to pick a recording format that will allow the most latitude for later post-production. The Sony S-Log provides a very good format for later grading, producing a file that is similar technically to a film Cineon DPX 10bit log file – but without quite the dynamic range of film, and slightly lower resolution. Ultimately, the 127 minute film was released in a 2.35:1 format, so not even all the 1080 line height was used. That being said the film looks really magnificent and compared to say I,Robot, has no weave and float or film grain issues.

Ron Ames, the film’s associate producer and visual effects producer, describes the backing up process. “We double backed-up everything. We had full labs in the truck. We captured to the Codex Digital Labs and it was backed up immediately to hard drives. At night, the drives were sent to an overnight lab where they were backed up to LTO tape. The LTO was also cloned, creating primary and secondary back-ups.”

This was important as, unlike some camera solutions, with the F35s in this configuration there was no tape or master other than the digital file, and unlike film, it is easy to produce a prefect clone of the master plate photography.

“We created our own dailies system with the help of Modern Video,” says Ames. “We first did a color pass on the set so that Mauro Fiore, the cinematographer, could see what he was getting. We kept track of those settings and they went to the lab. Our dailies colorist Eric would prepare full up, one-light dailies using the Codex Digital Lab and Truelight. They were sent to editorial and to screening, so that we had our dailies the next day.”

Everyone got DNxHD 36 dailies, but everything referred back to the original files. DD got DNxHD 36 dailies, and then access to the master files which Erik Nash found particularly useful.

“The great thing was there was no scanning,” says Ames. “We treated it like a scan order. One of the LTOs was sent to Modern Video and so we sent scan orders to them and they would pull it for us, just like a lab, only there was no scanning, so no there was no expense. Modern would simply put it on a drive and send it to DD and they would work with the clips exactly as if they were scans.”

If DD needed a few more frames, it was no problem, they could easily get them. They could get any material that they needed, whether it was reference from another take or frames because of a cut change, without having to redo everything. They could simply add the frames and continue processing.

Ron Ames describes the nature of the workflow:

“It was a wonderful way to work. All of the color that we did on set traveled to dailies and then from dailies it went to DD and it came to us in editorial. When we did the final color we were looking at the film the way it should look and we had all this additional information. That made the DI very efficient.”

“The color was not baked in so that got back frames the same way we gave them out, except, obviously, for the visual effects. So they would drop right in like shots in the movie. It was seamless. It was perfect. There were no bumps or hiccups or misunderstandings. We had all the information from all the shots all the time in the metadata. It had the shot name and stuff the visual effects editor required. The online conform was seamless. There were no bumps, no problems or trouble.”

“Having access to all the frames was also huge because of marketing. Marketing is so important because you have one shot at having the film come out and do well. So we built the system so that we had access to anything that might be needed. If someone were to say that this shot would be really good for marketing, we could give it to them. We could pull any live shot, or any visual effects shot for that matter, easily because everything was available. It was all color corrected so we could hand it off to marketing and they could have it for trailers or posters or stills or whatever they needed.”

“Everything was backed up redundantly to two sets of LTOs. We also backed up the final film. It all went to archive along with a full database. That was handed over to Deluxe and DreamWorks to put away in case they needed it – if they needed a frame, or were making Real Steel 2 and wanted reference. All the editorial information that our assistant prepared, everything that would normally go into his code book, was there.”

“The communication was clear and everyone was making the same movie. That is the great part of digital technology. Used incorrectly, it can be a Tower of Babel, but used properly it creates a great way to communicate. It is modern filmmaking at its best. Codex was invaluable for its ability to retain metadata recorded on the set and passing that into post, making tracking, animating, lighting and compositing vastly simpler. That improved our ability to understand what the director, the cinematographer and other creatives were looking for on the set, and we were then able to carry that through all the way to the end. It made it very easy for everyone to know what was expected of them and made everyone keepers of the film.”

Erik Nash agrees: “We recorded on the Codex and that was a fabulous way to go instead of swapping tapes. This was the first film I shot digitally and I would be hard pressed, from my own perspective, to find a reason to go back. Getting additional plates and material was so much easier. One phone call to the VFX editor on the production side and we’d have the frames on a drive that afternoon, no dust busting, no dirt or scratches ever, it was great.”

Stage 6: Animation, texturing and some great TDs setting up the pipelines

Giant Studios provided motion capture for the robot performances but they also provided what Erik Nask calls “Image Based Capture” or IBC of the robot stand-in proxy stuntmen. “We had a guy in spandex suit on painters’ stilts,” explains Nash. Giant Studios was tasked with cleaning up and re-targetting the motion capture data in both instances. What DD and Giant Studios collectively found was that even with the adjustments for re-targeting to adjusted joints, such as lowering the pivot point of the knee to the correct position, compared to the artificially high point it sits when someone wears stilts, the performance was still not quite right.

A behind the scenes shot of the basic animation rigs.“A lot of that IBC data we ended up not using,” says Nash. “Giant had some very clever ways to re-target the data and re-map them onto the robot’s skeletons, yet when you did that you could tell he was walking like a guy on painters’ stilts. It was funny how apparent that was.” Thus, traditional keyframe animators are vital and DD has an excellent character animation team.

CGI had key tasks to do on Real Steel – it was very important that the texturing and weathering of the robots was expertly handled, for example. These were fighting robots so they had more than minor scuffs, they had major gouges, crack, breaks, tents and damage, but DD also had car paint beautifully polished and finished versions to light, texture and shade.

Also while it is a given perhaps today, all the shots still needed accurate camera tracking and sizable amounts of pre-comp roto for ropes, crossing actors and props, especially given how little greenscreen was used in the film.

Stage 7: Have great compositors

DD used a similar multi-pass compositing approach as it had done with its Makebot Nuke plug-in for I, Robot. But as the Real Steel characters had no real translucency, the process was easier, although artists still did a multi-pass approach as a multi-channel OpenEXR.

Compositing has certain key tasks, such as:

• match the black levels;

• match the highlights;

• balance the mid tones;

• match the softness, motion blur and atmospheric conditions that integrate a shot;

• allow light wrap;

• match lens curvature and properties.

But, as you can imagine from the company that gave birth to Nuke, the DD compositors did a lot more than just standard multi-pass compositing. For example, in the end stadium shots there was a need for massively large stadium crowds. DD’s composite team delivered live action real stadium crowds, yet they never had more than 500 extras on set. One location in Detroit was used as two locations in the film.

A clip showing what was shot for the stadium. A clip showing the final stadium.Says Nash: “My digital effects supervisor Swen Gillberg and his team came up with what I thought was a brilliant solution to populating the arenas.” In the film, the sporting venues needed to seat a sold out crowds of of anything between 12,000 to 20,000 seats. While filming in the real arena, the team photographed in a separate space. They set up a small greenscreen with multiple Sony EX3 cameras. Then, each extra, with nothing but a green box to sit on, was brought in and filmed in a variety of poses, by three cameras simultaneously (shooting on their sides, tilted over for a 9:16 image) in a fairly neutral lighting. Each actor then went through a pre-arranged set of ’emotions’ or movements, such as sitting, sitting cheering, etc. The team then created a Nuke script that made a card at every seat location.

Then, based on the angle to the camera for the shot, the script determined which of the EX3 angles was most appropriate and selected that angle automatically. The DD compositors would specify a range of appropriate emotion for the crowd at that point in the story (for example, in the pre-show the audience would be seated and looking around, compared to later during the fight where it would have the crowd standing and cheering). Of course this meant that 12,000 seats meant 12,000 composited cards. In the end, about 65 different actors were used so a crowd of 20,000 people was made from just 65 actors.

Surprisingly, the render time was very fast and it was scripted so it was easy to change. “But of course,” says Nash, “as is the case with this sort of thing, we ended up using them much closer to camera than we ever expected, and it worked great. It worked better than any of us ever thought it would.” In face it worked so well that DD actually used this for a one-off crowd shot in another film, The Help.

Summary

There is no real secret to great CGI / live action integration. It comes down to:

• planning

• great on-set documentation

• a clean workflow

• a good team

• experience and a great eye

Luckily, Digital Domain has both the staff and the experience to bring exactly this type of work faithfully to the screen and the results speak for themselves.

Images and clips: Copyright DreamWorks II Distribution Co,. LLC, All Rights Reserved.

İts really a great article … İ think the best part is HDR’s … Btw i was reading it in my ipad 2 but seems like i cant watch videos … I wonder why … And if there is a way around it to watch them …

@cagri – No problems here. Videos played fine on my iPad 2.

today i saw this movie, Its Beautiful and inspiring work!

I can’t believe which shot is CG,

which software to assemble all these scenes , maya , max or something else?

It is best to listen to the podcast where we discuss this – but Maya and Vray

We were chatting about this last night (few of us got together in london), I wasn’t initially intending to see this film but I’ll have to now you’ve done the articles 🙂

Hoping you can get someone for a future 201/301 vray/maya class 😉

Pingback: Fx Guide Real Steel ~ eGlobal24.net