For Sam Mendes’ Spectre, the newest film in the 007 franchise, the effects requirements were, as with previous Bond films, diverse and complicated. Buildings had to be destroyed, helicopters crashed, cars raced around Rome, planes landed in the snow and a major location blown to smithereens. fxguide spoke to special effects supervisor Chris Corbould, visual effects supervisor Steve Begg and other members of the VFX team about how those massive effects were pulled off.

1. Mexican stand-off

The effect: After a lengthy continuous tracking shot following Bond (Daniel Craig) and a partner through Mexico City during a Day of the Dead festival parade, the secret agent attempts to take out assassin Marco Sciarra. Instead he causes an explosion that destroys the building that also topples down on top of him. Chasing Sciarra through the parade, Bond joins him on a waiting helicopter where a fist fight over Zócalo square occurs.

The opening one-shot sequence, and going into the helicopter fight, were some of the few shots previs’d for the film (by IO Entertainment). Begg used the previs to help the filmmakers work out how the passes – six in total – would marry up. “None of the elements were filmed motion control,” he says. “The end of the first pass had to be married up as best as we possibly can to the opening of the second pass. So I said to Sam and Hoyte van Hoytema, the DOP, whatever you commit to at the end of the first element you have to stick to that for the beginning of the second element, and then the second element has to match the same way. The previs helped a lot there. We’d previs the first segment coming to a halt and then we’d previs the second segment, and sometimes I’d get them to offset it slightly to show that if they do that and don’t follow through on the second segment these would be the problems you get.”

The Mexico plates were filmed in spherical rather than anamorphic to give ILM London, which worked on these opening sequences, more room top and bottom to do re-alignments. “For the one-shot, the joins were a combination of re-timing and re-projections,” explains ILM visual effects supervisor Mark Bakowski. “The first one comes on the door. We pause to look at a poster and they wonder up the stairs, up a lift. Then Bond goes into a hotel room and the hotel room is joining from Mexico City into Pinewood. We concentrated first on getting the performances to match because that’s what felt hardest to do. Everything was about getting Bond and his lady friend to feel like they flowed from one place to another. We were using people walking through as wipes to hide it. Then after that we massaged and warped and re-projected the geometric shapes so that they worked as well. When the doors open you’re looking from Mexico City through to Pinewood Studios and there’s a bluescreen window out to Mexico City again. So you’re seeing all three environments altogether.”

“They enter the room and there’s a whip pan where they cut out a bit of time,” adds Bakowski. “In fact, a large part of the sequence was re-sped by about six per cent which was a joy of artifact painting to deal with. The next big join is exactly where you expect it to be, as the camera’s going out of the window and Bond steps out onto the window back into Mexico City and walks along the rooftops. On the left hand side of the screen we topped up the missing bit of geometry where the hotel room would have been, because the whole wall is missing. On the right hand side we did a lot of rig removal – he’s on a safety wire and there are cranes in the street. After that he did a little jump over a gap which was a re-projected generated gap – all one complete building in reality. Then we get to the end and there’s another plate. Although the building that eventually gets destroyed is there in Mexico City, it wasn’t tall enough so we extended it vertically and then the room where the villains are making their evil plans – for some reason it wasn’t suitable for shooting in Mexico City – so that was shot in Pinewood and inserted into the shot.”

In addition to the stitches, ILM performed extensive clean-up to parts of the Day of the Dead parade. “There were thousands of extras so you never really get the perfect shot because some guy is always looking at the camera or so,” notes Bakowski. “So beyond stitching everything together and adding crowds, there was a lot of work fixing faces and putting masks and sunglasses on people.”

Bond shoots at his target but ultimately causes the building to explode. The explosion was crafted at Pinewood Studios, although Corbould says the resulting knock-on effect of the falling building was the most complex aspect of the stunt. “The building itself was CG as it crumbled down towards Bond,” he says, “but where we took over is that we made a fascia front which we dropped from 30 foot above down a track which impact with the end of the building that Daniel was on. The roof Bond was on was divided into three sections; there was a breakaway section that was hit by this building piece. There was a second section which hydraulically dropped after the second impact and there was a third piece that hinged down hydraulically with Daniel and the stunt person running off it.”

ILM took that practical footage and incorporated its CG building, building extensions and CG debris, plus – as they did for other shots in the opening sequence – digital double and face replacement work for Daniel Craig. “For the big hero shot of Bond running towards camera and leaping and landing on sliding floor, we ended up just keeping the stuntman’s torso,” says Bakowski. “The rest was face replacement for Bond and CG environments which effects destruction. Then he goes through a series of slides within the building, which required face replacements, lots of effects augmentation. He was on a big platform on a lever that collapsed at various points and he would just leap from place to place – like a trapdoor – and we had to remove that and replace that with a crumbling floor and various debris falling past him.”

Unsuccessful in killing Sciarra, Bond chases him to the central plaza where a helicopter has landed. Both board and a fist fight ensues as the chopper takes off. Real helicopter stunt flying and backgrounds were combined with CG environments and crowds, with the fight scenes filmed on a helicopter gimbal. Begg had made an early request to the director and DOP for as little smoke to be used in the distance in order for crowds and digital buildings to be inserted into the plates. “I managed to get a fairly good rapport with Hoyte, to a point where I said is there any chance the smoke way in the background – can we kill that? I totally understand in the foreground. It’s more diaphanous, so believe it or not it’s probably easier to comp things through it, but further away it gets the more moving detail it gets in it. I felt it would compound the final shots. Particularly when we got into the square, Hoyte would completely kill the smoke and ILM would add it back in.”

Since the helicopter sequence would involve a frenetic airborne fight that would see views of the square and crowds, the production embarked on a major survey and scanning period before and after principal photography. “We used Propshop who have a surveying and photogrammetry setup,” says Begg. “That team went out ahead of us and surveyed and photographed the hell out of the square and the immediately surrounding buildings. They also used a drone camera to shoot the rooftops. At the end of the shoot, I stayed behind and went up in the copter and stopped it at different altitudes and got the pilot to spin the camera around slowly. It was a hand-o-matic to be used as tiles, basically.”

“With the drone,” says Bakowski, “we covered the area around the main square where the flight happens in quite an amount of detail and a couple of blocks back. Obviously in any built up area there’s aerials and flags, so it was a bit up and down in quality because the drone would have to be adjusting itself all the time. But in the end the results were still really amazing. That was brought back to ILM and with photogrammetry tools we re-modeled the area, touched it up and from that point onwards, sections we captured from there would be re-purposed for the middle distance, with variations applied. Beyond that we had a really nice library of aerials and flags and solar panels and all the things we needed to dress into places. It really helped us give more of a sense of danger and parallaxing. You’d be flying over a building and we found that if you can get something reaching up to the camera a little bit it made it more interesting to look at, gave it more visual interest and more parallax and depth and peril. We took a few liberties sprinkling bits of street furniture and other things on the rooftops.”

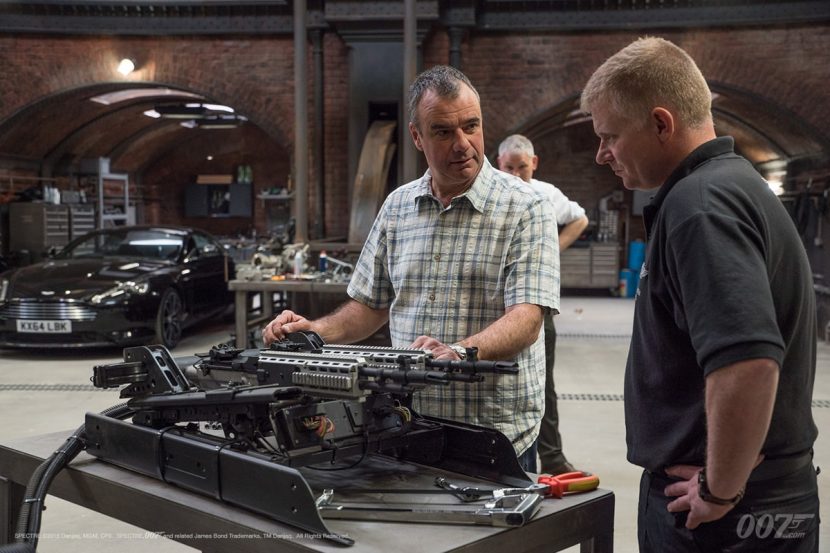

The scene involved real helicopter footage over the square, additional plates shot at an airfield for safety reasons, ILM’s digital helicopter and bluescreen photography of the aircraft. “We had three bucks mounted on different gimbals,” explains Corbould. One of those was a traditional 6-axis gimbal like you would see at a theme park. It was a motion base that let us spin it around, rotate it, very very fast on either axis.” Some extra pieces were also captured to help sell the spectacular barrel roll and somersaults performed by the real helicopter. “For those,” says Corbould, “we built almost like a spit roast. We had the fuselage of the helicopter mounted between two pivot points, one on the nose and one on the tail so we could actually rotate it 360 degrees. That gave us our barrel roll so we could keep spinning that round as long as we liked. Then we turned it 90 degrees and could turn it end over end, for the loop de loop part. Those few shots with these rigs made it all the more believable.”

ILM added a CG environment or plates outside the window and added lots of flicker and camera shake to the bluescreen helicopter shots. “Generally when doing the heli,” notes Bakowski, “everything would be shot without glass in the windows to avoid reflection issues from the studio lights. We’d then have to put in the glass, the rotor blades, the rigs from the rotisserie rig. Sometimes they’d be spinning around quite fast so the actors would have to have lots of restraints on them to stop them falling out. Then there’d be shadows coming in from everywhere so we’d be patching up sections of the heli and extending it. And smoke coming out the back when a flare gets shot out.”

Daniel Craig had earlier injured his knee during the production and could not perform every part of the sequence – this necessitated the use of stuntmen and therefore head replacements and digi-doubles. Begg and ILM approached the work with both 2D and 3D solutions. “I said to the production,” recalls Begg, “just realize that head replacement isn’t a science. Sometimes it can work really well, flat 2D ones in particular, but 3D ones are trickier ones because you want to avoid that dead look you get and the plastic finish on the textures. In some shots we’d start with a 2D Daniel Craig face shot against a bluescreen. It would then blend or wipe into a 3D head when it was a much more difficult position for him to mimic. There’s one shot where the helicopter is doing a barrel roll, and Bond is nearly thrown out the side door by gravity. The shot begins with Daniel looking directly at camera, you get a damn good look at him – that’s the 2D Daniel – and as his head turns down we go into the CG head. There were shifting lights and shadows meant we had to go 3D. I take my hat off to ILM for pulling that together.”

“It’s interesting,” notes Bakowski, “Daniel Craig is a very stoic actor – he’s not particularly expressive and he has this classic chiseled cheek look and slight pout, and when you see him doing it for real it looks like Daniel Craig. But when you see a digital double doing it, it can look dead. So then we got a lot of comments about bring him to life and adding in performance, but then the performance we added started to break him looking like Daniel Craig, so it was a vicious circle. That’s why we often went with the plate approach. The small and mid distant head replacements still used a digi-double but the hero close-ups were mostly plate – you couldn’t really argue with it and they had this essential Daniel Craig-ness about them. In some ways you can’t replicate reality because it’s not aesthetically pleasing all the time.”

On set, there were around 2,500 extras which were filmed in pockets for both use in the sequence and as reference, but the majority of crowds was achieved in Massive. “We did a big two-day mocap session at Centroid,” says Bakowski. “The first day was crowd mocap where we had rhythmic dancing to the parade for the crowd dancing. Then they’d do pointing at the helicopter or scattering and ducking, falling over. We did lots of little vignettes of people lifting others up or helping. Little bespoke motions that we could parachute into a scene at a hero point. The second motion capture session was all about the stunt fighting in the helicopter. We used much less of that than we thought. The physics of trying to pull that off were quite awkward, we were trying to do mocap of a fight in a helicopter that’s spinning round and round, and it’s upside down at some points so the people are spinning around inside there. The best we could do with our mocap actors was attach them to tug-o-war-like ropes and be padded up. People would pull them around within a cage to simulate gravity going up, down, left right as if the helicopter was rotating itself. That was used as a mimic of the actors within the heli.”

One signature shot – in which the crowd parts for the approaching helicopter – made use of only a small portion of real crowd and then ILM’s motion captured extras. “That shot is a great example of where we managed to collaborate with the DOP in getting the smoke switched off,” says Begg. “All the smoke has been added in in that shot. That is less than 25 per cent live action crowd and everyone else – we probably filled in 20 to 30 degrees of that circle with real people, and the rest of it was the motion captured ILM people. What even stunned me was on a big screen you can’t tell the difference. The movement, the performances, are so believable. It’s amazing. I’m very proud and pleased with that shot.”

“We got into heavy cloth sims as well because of the down draft of the chopper for that shot,” adds Bakowski. “But about 85 per cent of what you see there is CG crowds. That was one of our lookdev shots. At one point we had Wally from Where’s Wally in there with a stripey top, but then they didn’t take that to the final…”

2. When in Rome…drive fast and up walls

The effect: In Rome, Bond discovers the existence of a criminal organization called Spectre, and soon finds himself being chased in his gadget-fitted Aston Martin DB10 by one of its henchmen, Mr. Hinx (Dave Bautista) in a Jaguar C-X75 through city streets and along the banks of the Tiber River.

Corbould’s team worked closely with Aston Martin and Jaguar on producing action cars that were extensively tested for the chase sequence, which included moments in which the cars jump through the air, take the roof of an Alfa Romeo, drive down steps and zoom along sideways on the river bank wall. “Those tests,” says Corbould, “were almost to the point of destruction to find out any weak leaks. Our main priority is to ensure the safety of the stunt drivers and the camera crew, but also being in Rome, we were driving these cars around 2,000 year old buildings and if a wheel came off and we hit a building that would have been a disaster.”

Remote driving pods on the top of the Aston Martin and Jaguar were also constructed so that the cars could be driven by a stunt person on the roof while a camera focused on Craig or Bautista. “It meant we could do high speed shots through Rome looking like Daniel or David were driving,” notes Corbould. “Whereas in fact there was a world rally champion sitting on the roof driving the vehicle.”

The most elaborate stunts in the sequence involved the river bank wall shot and a drive down some steps. “We had rehearsals for the wall shot at Longcross Studios,” states Corbould. “They built a section of river bank wall that the stunt guys rehearsed going up. The steps were also rehearsed, but actually there in Rome on the actual steps. Construction had to do a lot of protection work on the steps because again these were 2,000 year old steps so the authorities didn’t want them damaged in any way. All credit to the construction crew in strengthening them up and covering them in such a way that we looked like we were going down the authentic steps, but actually they were heavily protected.”

Finally, Bond attempts to throw Mr Hinx off the chase with one of the newest gadgets in his Aston Martin – a flame thrower. “That was something we also did extensive testing for,” says Corbould. “We had to change all the exhaust system over because the flames came out of the exhaust.”

The Rome sequence featured some visual effects additions too, mostly completed by Cinesite. These included rear projections, rig removal, camera and light removal and a few matte paintings to “make Rome look more like Rome,” says Begg.

“One of Cinesite’s earliest challenges was to prepare all of the Rome streets footage that was to be used on set during the shoot for the car interiors,” outlines Cinesite’s Zave Jackson. “DOP Hoyte Van Hoytema was keen to use a rear projection technique as it gives convincing interactive lighting on the actors and vehicles. Cinesite stabilized and graded almost 70 minutes of 3.5k Alexa footage. This was shot on nine separate cameras mounted on a custom camera vehicle that traveled the specific streets in Rome that made up the carefully choreographed car chase. In many ways the method proved successful, but as the Rome sequence was at night it was also often necessary for the final shots to have background adjustments made. This meant rotoscoping the foreground and re-compositing the relevant stabilized section of footage. This allowed us to adjust the look of the defocus, tweak perspective and correctly represent the intensity of the background city lights which, despite the power of the on set projection set-up where not captured on film correctly.”

During the chase itself, Cinesite added digital gun barrels to the Aston, car interior to the Alfa, debris, shattering glass and sparks to collisions and SFX flame elements to the Jaguar. “We also removed extensive production lighting set-ups, unwanted reflections, safety barriers, tyre marks, cranes, scaffolds, ramps, cameras and cables,” says Jackson. “In some shots we digitally extended the length of street, adjusted the distance between the chasing cars, face replaced stunt drivers, re-timed shots and added a CG ejector hatch to the Aston to ensure the action worked within the edit.”

3. Snow-planing

The effect: In Austria, Bond tracks down the daughter of former Spectre member Mr. White, Dr. Madeline Swann (Lea Seydoux). who is abruptly kidnapped by Mr. Hinx, starting a whole new chase sequence. This time Bond is in pursuit of Land Rovers by a plane, which he crash lands to dramatic effect through snow-covered trees and a barn.

As with all the film’s stunts and effects, Corbould discussed the plane sequence heavily with director Sam Mendes, Begg, stunt co-ordinator Gary Powell and second unit director Alexander Witt. “Our first task was to find somewhere where this could be filmed, and we did, a valley in Austria,” says Corbould. “We had to drop the plane down into this valley of trees with literally only three or four feet from the wingtips are trees. Obviously it would be very dangerous to fly a real plane there so we put a crane up at each end and did a 160 meter run of this plane coming down on a wire. It comes down the wire from the top, lowers down amongst the trees and carries on until its wings get cut off and then belly flops onto the ground.”

Above: An image from stunt co-ordinator Gary Powell’s Instagram page showing the crane, plane and Land Rovers in action.

After meticulous planning for one part of the effect where the plane hits and rips the top off one of the Land Rovers, the filmmakers struggled to make the stunt work – until they made a surprising finding. “We were pulling the plane backwards and forwards with glider winch which is used to help gliders take off. We brought the plane to the collision position and lined up the height of the plane with the height of the Land Rover, then we brought it all back to get the shot. Weirdly the plane was six foot above where we’d set the height. We deduced from this that we were getting the plane up to such a speed that it was trying to take off! So we actually had to slow down the plane to get the impact right.”

Once the plane landed, an array of stunt planes were used to show its wings coming off and then planing down the valley. “We crashed the planes into real trees but we changed the wing tips so that they were lightweight sections and added some pyrotechnics in there, so when they made contact you saw the wings sheer off and it bellies into the ground and we ploughs into a big pile of snow,” explains Corbould. We had two planes mounted on the wires with wings coming off. We had another two or three planes where we built into the plane fuselage a double track skidoo, so we mounted that in the plane with a ski out the front. That meant the stunt driver could drive it down the hill as if he’s driving a skidoo.”

Eventually the plane careens into a barn full of firewood, exiting out the other side. “For that shot we mounted our plane section on a nitrogen canon and literally fired it out the back end of the barn,” states Corbould. “It was quite a tricky sequence especially when you’re dealing with sub-zero conditions with snow storms going on. But everybody rallied around and it was an exhilarating time.”

In terms of visual effects for the sequence, MPC was called upon to add CG propellers, clean up the skidoo skis and work on some snow and environment fixes, but the studio also crafted a fully digital plane for shots seen once it drops below the tree line and does the ‘touch and go’ bounce. Their shots included, too, compositing on-set stage shots filmed with the plane on a gimbal. “Because it was a nice shiny black plane, I thought we would have a lot of problems with it on a stage if we filmed with the bluescreen around it,” notes Begg. “And then even before we put the screen up the plane was on the stage and you could see every light and everyone reflected in the surface. I suggested to Hoyte, why don’t you just light this with white everywhere? He loved that idea – most DOPs hate bluescreens. What you get is much more natural bounce light everywhere and MPC were going to replace the fuselage and what’s behind it a lot with CG anyway. What I loved too is that they also added reflections off moving trees and mountains into their CG fuselage, which gave the impression it was more of an air-to-air shot.”

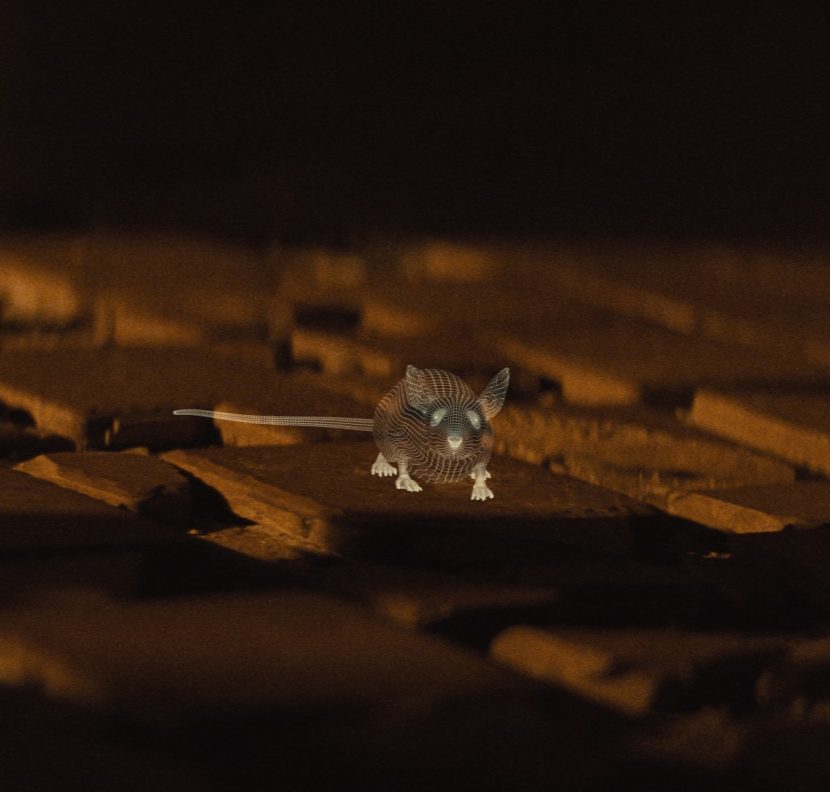

3a. Mouse in the house

The effect: It might not be one of the film’s grand action scenes, but it’s certainly a key one. A curious mouse alerts Bond to the location of a secret room at the L’Americain. Cinesite crafted the mouse digitally.

“Our start point for the mouse were image selects made by Director Sam Mendes,” outlines Cinesite visual effects supervisor Zave Jackson. “These gave us initial direction on size, colour and the disheveled look required for the fur. The path taken by the mouse and its position in frame had been carefully considered by the films editor and a post viz sequence was provided for us to work to.”

Cinesite’s Director of Animation Eamonn Butler oversaw animation work on the mouse. “Although we had editorial marks for timing and position we were keen for its movement to seem spontaneous,” says Jackson. “Animator Sandra Guarda worked hard on this, incorporating a syncopated walk cycle and using extensive online video reference. The goal was to avoid any feeling of choreography and to get its behavior and movement feeling accurate and natural.”

Cinesite worked closely with VFX Supervisor Steve Begg throughout all the stages of the mouse development. “As the scene was in low light, Steve was keen to exaggerate certain features of the mouse so that the audience would spot it easily,” notes Jackson. “Sub-surface scattering in the lighting gives a partially transparent appearance to the thin, fleshy areas of a mouse such as ears, feet and snout. We paid particular attention to this in the lighting and at the comp stage. This gave a realistic look to these parts and created areas of the body that would catch highlights and stand out.”

For the mouse’s groom, creature FX artists Wiebke Sprenger worked to provide the appropriate level of clumping and root to tip texturing. Says Jackson: “The scruffy look created a detailed surface texture that once lit gave compositor Alex Webb more opportunities to accentuate the mouse even in the low light of the hotel room. Low light coupled with anamorphic footage shot at close proximity gave a very shallow depth of field and particular care was paid to matching this accurately. Alex also carefully balanced the CG renders into the footage with a lot of grading work, shadow interaction, even adding tiny footprints in the dust as the mouse runs through the hole in the wall.”

4. Hi-jinx on a train

The effect: Bond and Swann take a train trip through Morrocco to a secret lair. Here, Cinesite made CG carriage additions and completed head replacements and rig removals for a fight with Hinx.

“We created a full CG train for use in scenes after Bond and Madeleine leave Tangiers, the train available to production at the time of shooting did not have the correct number, or type of carriages,” explains Cinesite’s Zave Jackson. “In several exterior shots we extended the train from four to seven carriages with part of our full CG asset. We made sure the configuration and type of carriage matched that seen as the fight between Bond and Hinx passes from the restaurant car, into the bar and on into the kitchen and goods carriage. Particular attention was paid to the exterior texturing and displacement of the train as it is seen close to camera at one point, scratches, scuffs and dents and a subtle rippled effect to the coachwork panelling were added to make it feel as authentic as possible.”

“As the three sets for the different train carriage interiors where ultimately on different stages at Pinewood,” adds Jackson, “green screen back drops were hung where the view through to the next carriage would be visible. We used a 2.5D digital matte painting approach, projecting imagery based on HDRI photo reference taken on set. This was in order to recreate backgrounds for restaurant, bar and kitchen carriages that would move and parallax correctly with the dynamic hand held camera moves used during the fight.”

A frenetic fight takes place between Bond and Hinx (and Swann) on the train, in which Cinesite was called upon to produce head replacements for both 007 and the henchman. “I think the most impressive replacements were when Bond douses Hinx in some liquid from a lamp and sets him alight,” comments Begg. “We had Dave Bautista’s double on fire with a 3D head. We went for a 3D head because of the interactive light from the fire. We did shoot Dave going through the motions, but the light values and shifting light on him just didn’t match.”

“Cinesite’s team were supplied with 3D head scans and photographic reference of both actors in costume for the scene,” says Jackson. “These were used to build digital assets at a high level of detail, as required by the medium distance shots. This included a high quality groom for their hair and Hinx’s beard. Also accurate matching of skin textures using the cross polarized and parallel polarized reference images of the actors supplied by production. We also constructed a full facial rig so that we could create all the expressions required. However, we quickly learned that the animation of facial features required a subtle approach. More extreme facial poses would quickly detract from a convincing likeness to the viewers perception of how the real actors look.”

After Bond throws the oil lamp at Hinx, setting fire to his jacket, there were five shots where Cinesite created a full CG head replacement for Mr Hinx. Bond’s head is also replaced in two of these. “The stunt double’s head was carefully match moved and our CG Hinx or Bond head asset tracked in,” states Jackson. “Animation then took over using the stunt double’s movement as reference for a first pass. In the case of Hinx the stunt double was understandably keeping his mouth closed so we then added to this base layer of animation. Using aspects of Hinx’s facial performance seen in surrounding shots as well as other reference shot on set we introduced open mouthed growls and grimace poses that would hopefully catch the eye in a midst the speed and energy of the scene.”

Cinesite relied on Arnold to render the CG heads, one of the first times the studio had utilized physically plausible shaders to ray trace both skin and hair. “This allowed us to take maximum benefit from the on set HDRI photo reference,” says Jackson. “Whilst we were extremely pleased with the look of our lit CG elements for these shots the final work done in the comp gave us the flexibility to really match the look of the lighting on the set and the play of the fire light on their skin. Rather than try to match the animation of the fire light in the lighting render we concentrated on matching the lighting direction. This was rendered as a separate constant layer. In the comp we where able to introduce the correct amount of fire light on the skin, adjusting and tweaking on a frame by frame basis to get an accurate match to the skin tones of Mr Hinx and Bond.”

5. Boom! Blowing a lair sky high

The effect: Bond and Swann are held at the Moroccan communications facility run by Spectre’s leader Ernst Stavro Blofeld (Christoph Waltz), but escape and destroy the buildings there in a dazzling wave of fireballs.

The explosion, crafted by Corbould in partnership with Event Horizon’s Charles Adcock, involved 8,140 litres of kerosene and 24 charges each with a kilogram of high explosives. It was recently awarded a Guinness World Records title for the largest film stunt explosion. In the planning stages, Corbould says he suggested to Mendes he could create an explosion that would ‘blow him away.’ “The explosion was all real, but the CGI guys did a great job putting in the whole complex there too. There was very little of that set that was there when we shot it.”

For the blast itself, the effects team looked to do something ‘different’. “We created this whole great arcing where it arcs around the outside and then it comes straight up the middle towards the actors,” outlines Corbould. “We had them right in the foreground on a helicopter pad. And that was very exhilarating. It went away from us first in a big circle and then came back towards us. The crescendo slowly builds and the shockwave comes towards us.”

The explosion was detonated using individual detonators each containing a computer chip that communicated to a central unit. “There were about 300 detonators involved in that whole thing,” says Corbould. “It’s quite extraordinary – they’re all linked by one wire. You program each one up to a 1,000th of a second. You program that all in and then you press the button and off they go. It’s quite eerie because after you press the button there’s a three second delay where all these initiators all talk to other to say they’re ready. We had to tie in with a line of dialogue from Daniel which was pretty funny because you’re literally pressing the button half way through his line of dialogue from the three second delay. If he’d got the line of dialogue wrong we might have had a bit of a problem on our hands! But we rehearsed it and rehearsed it until we were absolutely sure we’d got it. There was a beam on everybody’s face after we let it go, and Daniel and Sam were high-fiving.”

Earlier, Corbould’s team test explosives for about 10 days prior. “It’s like a recipe for a meal, really,” he notes. “You get all the ingredients together and then mix it up in such a way that you get a great end result. It’s a mixture of high explosives, some black powders, combined with fuels, some were just combined with dust and debris flying in the air. We wanted to give the feeling that the CGI building that would go in there would be flying apart, so we put a lot of explosive just under piles of debris, big bonfires that literally flew apart sending a shower of debris into the air.”

ILM Vancouver was responsible for the CG buildings of the lair, which are seen in much detail as Bond and Swann arrive and are taken around by Blofeld. Very little of the final on-screen structures were present on set. “The buildings and crater walls and distant terrain are mostly in post,” says Begg. On location, whatever the actors had to walk on or react to, we had a piece of set piece. When they arrive, all we had there was the immediate flat of the side of the building with some windows in it. There was some terrain and some astro turf and nothing else. The whole environment, foreground water sprinklers, a distant swimming pool – all added by ILM afterwards.”

“Then as we walk around the complex,” adds Begg, “the only thing that’s real is the ground they’re standing on and a small piece of set from the domed building. I had a distant goal post put out in black in the middle of this location to give the camera and the actors something to line up to and walk towards.”

For the explosion, Begg initially suggested to Mendes that it could be captured with multiple cameras. “I thought there could be some effects cameras out there so we could shoot 2D elements if something goes wrong or get other angles. Sam said I don’t want any other angles – I want one angle and I don’t want it to look like a ‘pyro-maniac-fetishing’ of the explosion. None of us completely believed that, to be honest, but he stuck to his word, which is why it’s much more impressive. It’s incidentally utterly spectacular in the background.”

“What you’re looking at there,” continues Begg, “is the third take of them coming up there, doing their bit in front of the camera and the explosions going off – less than a quarter of a mile from them. The reason it’s the third take is that I managed to talk Sam into doing a couple of safety takes with no explosions going off and if we needed to we could add things in afterwards – should they go wrong. Then we shot it for real and it was a cascading sequence of explosions, each one bigger than the last, and I think everybody thought, Oh my God it’s coming nearer to us! It shook the cameras and the ground.”

ILM Vancouver, under visual effects supervisor Greg Kegel, then had the challenging job of extracting the explosions to engulf their CG buildings. “It’s a real credit to the comp and painting department,” says Bakowski, “because if you’re extracting one explosion edge against another explosion edge and you’re trying to layer in z between those two things, it takes a bit of judgment about where to start one and stop the other. We also made heavy use of interactive light so when the explosion is happening you slightly precede the event with the interactive light of the explosion and that beds that in there and helps sell it.”

“Effects-wise,” notes Bakowski, “there was some augmentation to what happened in terms of damage to the buildings themselves – we’d allow the flames to burst through at certain points. Then there was smoke carefully placed on top. There were also 2D elements that helped sell the shots. Even though we had this huge explosion, adding in plate explosions from our elements library could also help define a few edges and let you layer in a building in front or behind the explosion because it gave you a defined edge from the library explosion.”

Interestingly, ILM also started out experimenting with some RBD effects for the explosions. “There’s some small ones on the left and right but the majority of it is static,” says Bakowski. “It’s all about lighting and interaction. We started with towers falling down and things collapsing but the feedback from Sam Mendes was ‘play it down, play it down’ – we don’t need to overplay it. Instead our initial tests on the RBD explosions became the initial basis for the destroyed bits that you see in the following shots. It would be passed to our matte painting/generalist department and touched up. So when the helicopter flies away through the smoke over the destroyed base, the glimpses of the destroyed base is the result of the RBD FX passes painted up and art directed.”

5. Tense times on the Thames

The effect: The film’s climax involves two major stunts with Bond and Blofeld – the first is the destruction of the unoccupied MI6 building, followed by a boat and helicopter chase along the Thames before Blofeld’s chopper crashes on a bridge.

“Sam really wanted to do the external view of MI6 exploding as a miniature,” says Begg, “but I was very weary of it. We did have one go at it and basically the miniature was used for cutting purposes. The issue for me is that, miniatures, particularly when they are collapsing buildings, have to be strong enough to support themselves pre-demolition, but weak enough to break up and fragmentise into pieces when they’re demolished. That’s physically hard to do in the real world.”

A miniature was constructed and set to explode, but in parallel Begg had Double Negative build a breakaway MI6 building in CG. “The miniature did mean that we constrained the camera to the right position and use those real-world angles,” notes Begg. “We shot actual location plates from bridges, but Dneg put their CG building in the background. Dneg also produced early views of the damage to the MI6 building. I was very anal about those because I blew up the building in Skyfall as a miniature so I wanted to make sure all the damage and carnage on that and destruction was there. It was done as two and a half D matte paintings on top of the real MI6 building on location.”

Corbould handled interior views of the MI6 explosion. “Originally,” he says, “we were just going to do the MI6 explosion all from the outside. But we had the whole set at our disposal so we figured why not use it? We rigged every part of that set in the end with this series of explosions exactly as you would do in a real demolition of a building. I didn’t just want to do a normal demolition. So it was very very fast, which is how it would be really done in an actual demolition. When you do a demolition there are slight delays between all the explosions because you don’t want all the explosives going off at the same time creating this massive great shockwave. So you split the shockwaves up. It’s 30 explosions going off but with split seconds between them. We did that over four parts of the set which cut together only lasts about two or three seconds.”

The action then moves to Bond chasing Blofeld. 007 shoots down the helicopter causing it to crash onto Westminster Bridge. Double Negative enhanced backgrounds for the Thames sequence by winterizing the surrounding areas (since the shots were filmed in summer) and added CG traffic.

For the helicopter crash, Corbould urged the director to realize the sequence full-scale. “We could have had a miniature approach for this, but I said to Sam, I really think we should do this for real, this is what I get a buzz out of doing. It’s easy these days to say leave it post production, but the filmmakers are not like that. Sam wants to do everything for real.”

“We located two full sized helicopter shells and we put the steelwork in them,” adds Corbould. “We rigged it up in a similar way that we did the underground train on Skyfall with an overhead track. Literally like an overhead rollercoaster track. It clips the top of the first hand rail on one side of the bridge, lands on the bridge, skids across the bridge and then hits a lamp post on the other side. This track replicated that move. From that move, the helicopter whole and solid struts down from that track – we pulled it along like a rollercoaster, rigged the height of it so that it clipped the first balustrade on one side of the bridge, landed hard on the bridge, we had a few sparks as it skids along, and then we wrapped it around the lamp post on the other side of the bridge. We had two goes at it, and we got the shot in the first go. Sam was happy with it. I said well, now we’ve got it in the can, let’s go for it the second time. So the second time we cranked up the speed and came through at double the speed – and to the eye it looks fantastic.”

Double Negative augmented the downed helicopter with CG rotorblades and some destruction, plus a gouged road surface and the addition of emergency personnel on the sides of the bridge. The studio’s main work on the crash, however, turned out to be the environment. “We had translights and light boxes put up to reflect onto the wet downed road surface of the bridge,” explains Begg. “Unfortunately they put down the most water absorbent tarmac onto this bridge that you can get so we didn’t have any reflections whatsoever! The translights didn’t work as intended, so for every single shot Dneg had to do a major roto job where they removed the translights and put in a matte painting of the Westminster environment.

For Corbould and Begg, the combination of practical and digital effects continued the Bond franchise’s long association with both approaches. It was also one of their biggest effects experiences, partly due to the scale of the stunts but also the many locations and setups in which production filmed. “One day we’re blowing the front of the Mexican building out, the next day we’re collapsing the building, the day after we’re doing explosions at MI6, the day after we’re crashing a helicopter. There were times I went home in the evening my head was spinning!”

“My background is practical effects and in miniatures and then I moved into matte painting and other effects,” adds Begg. “So when we come into the digital world, it’s the same for me – I’m very open minded about how to approach things, so when I’ve done a sequence in the past we go about it in a variety of ways. My only concern is that it all meshes together in the end.”

BONUS – Peerless’ invisible VFX

Peerless Digital Imaging Ltd worked on several sequences in the film, including the Nine Eyes meeting in Tokyo, scenes of Bond with M in London and the film’s final shot as Bond and Swann drive down Whitehall. fxguide asked Peerless visual effects supervisor Paul Round about the work.

fxg: How did you approach the Nine Eyes meeting?

Round: That was shot on the top floor of City Hall in London. The challenge with that was that you’ve already got a skyline out the windows. You’ve also got many layers of glass. There’s a floor to ceiling glass wall and beyond that there’s a little walkway with glass going around that as well and multiple reflections. Which means it couldn’t be done as a greenscreen shoot, so they basically just shot it. It was lots and lots of layers of roto. Then we had a matte painting environment that was 3D tracked in.

The work was all done in Flame by Paul Gill and all the roto by Elliot Round. Because it was shot on anamorphic film and against a night backdrop, there’s very little definition between the hair of Andrew Scott playing Max which is really slicked back, you couldn’t really see an edge so there was a lot of tweaking and massaging of roto for that.

For the matte painting you have lights that you de-focus which gives you really nice bokeh. Paul then introduced some atmospheric distortion to give it some life, but not so it looked like lots of lights moving around. There’s just a little bit of movement within the matte painting that you get naturally within a cityscape. You had to create the feel that we were looking through separate layers of glass rather than just one, too.

fxg: What about the car shots with Bond and M?

Round: The first time you see them they’re coming through a park. All the shots in London were filmed in summer so they were full leaf but we had to de-leaf and winterize the environment, which was a mixture of CG trees fixing the trees and then putting buildings behind them. There’s lots of horizontal blue lens flares, so often we had to re-build all the trees in CG and re-build the lens flares.

Then the car turns into a tunnel, which was a combination of an existing tunnel which we then had to modify to link it in with another location where they’re driving down the tunnel and get t-boned. The side of that tunnel was covered in crash panels so they had to be removed.That was all hand-held camera, and had reflections and shadows from the headlights. They had panels along the tunnel to protect the concrete, so we had to remove those, re-build all the lighting and create the distressed dirty concrete look. There were a couple of shots where there’s a second camera on the ground so that had to be removed.

fxg: For the final White Hall shot where Bond and Swann are in the DB5, what was involved there?

Round: When that was shot one of the buildings on the left was covered in scaffolding so we had to re-build the building. We got a phone call from the producer to say they’re just putting scaffolding up, so I ran down there with a camera and shot as many stills as I could.

It would typically be a CG job, but it was a 3D build done within Flame – all projections on a 3D model. And on the shoot at 5am in March, the interior of the car misted up. They had to put a heater inside to clear up all the mist. The car drives away and there’s actually a heat haze coming out of the top of the car. So if you look at that shot, there’s lots of signs and lamp posts so they all have a warpy feel on them – so we had to match that heat haze otherwise it looks like it’s wobbling.

All images and clips copyright © 2015 MGM Studios.

Great article!!! Its candy 🙂