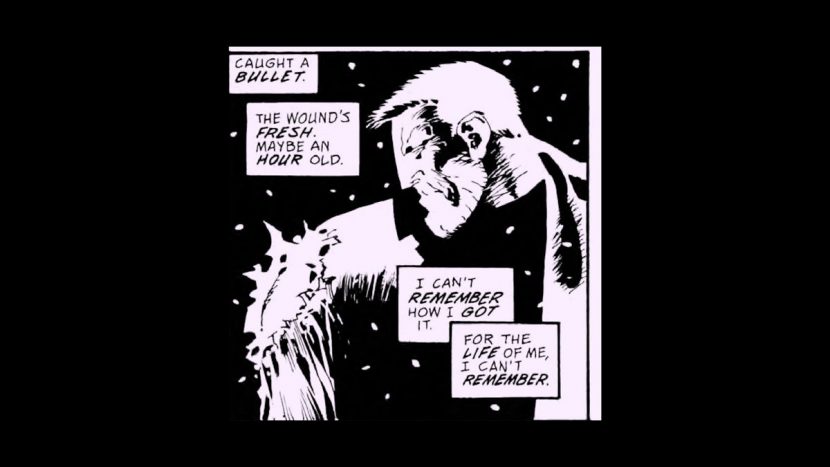

When Robert Rodriguez and Frank Miller’s Sin City opened in 2005, it hit a chord with audiences who latched onto the graphic novel come-to-life style. For the sequel – Sin City: A Dame to Kill For – the directors once again would film live action photography against greenscreen, only this time in stereo, and then orchestrate a mix of black and white, high contrast and coloring to tell their story. Helping to bring that stylized vision to the screen was Prime Focus World, which became an equity partner on the film and sole provider of the visual effects and stereo conversion work. We break down the steps in making A Dame to Kill For possible.

Rodriquez shot A Dame to Kill For at his own Troublemaker studios in Austin, Texas with ARRI Alexa M cameras and the Cameron Pace Fusion stereo rig. The directors then cut the film from that footage, ending up with literally a greenscreen version of the story.

Tasked with more than 2,000 visual effects shots and stereo conversion to be completed in around 8 months, Prime Focus leveraged its offices in Vancouver and Mumbai to complete the work. Visual effects supervisor Jon Cowley oversaw Canadian production, while visual effects supervisor Tim McGovern was based in Mumbai. Overall visual effects supervisor Stefen Fangmeier also came on board to creatively spearhead the global effort.

Prime Focus co-founder and chief creative director Merzin Tavaria told fxguide that a major challenge for the studio was walking the fine line between keeping the shots stylized and making them photoreal. “It actually doesn’t look right if it’s too real,” he says, noting that the team followed Miller and Rodriguez’s lead in what to stylize. “But it was never about just following Robert’s instruction – it was more about giving us the artistic freedom to arrive at our vision.”

Watch how a scene featuring Jamie Chung as Miho was filmed on greenscreen.Ultimately, Prime would complete 2,282 visual effects shots with a VFX crew of 702 and a stereo team comprising 1,502 artists. Almost every location, prop and asset seen in the film were digitally crafted – in fact the final number of assets created was 1,572, with 65 locations built as CG environments.

So what was the approach this time around – and 9 years later – for a Sin City movie? Fangmeier says that although technology has certainly advanced since 2005, “it was more about the visual style. Sometimes we veered more towards photorealism than the first film, but we also stylized it quite a bit more in places here and there to give it some variation. We actually approached it as being in-between an animated and live action movie. Every shot needed layout, postvis, animation, compositing et cetera. So we approached it as sequences rather than shots.”

The final scene showing Miho and her adversaries.Prime Focus artists worked concurrently on roto, layout, set builds and animation. “In terms of roto,” says Fangmeier, “we were fairly successful about pulling the actors out and then thinking about how were we going to treat their faces, the grade, going to black and white, the high contrast. Then once we had gone through that step, then we looked at what’s next – what environment has to be put behind it.”

“For that,” continues Fangmeier, “we needed to do layout. We had to get the camera information. So let’s say you do two characters talking in a room, they’re walking around a little bit or sitting down, and then the question becomes where are they in the room and how does it spatially work out? Because on the greenscreen they’re not always working in the same volume of the room.”

That process also involved what Fangmeier describes as ‘interior decorating’. “For most of the environments,” he says, “we created a lot of interiors – domestic spaces like a bathroom or living room. Floors, walls, ceilings. That was fun. We had some understanding of the economic means of each character and what sort of setting it would be, too.”

“You build fairly simple objects,” adds Fangmeier, “but then when you textures and bump mapping and displacement mapping you can add all that level of detail – plus strong specular lighting – so it creates similar to Frank Miller style. He does just full black and full white in his work – there’s no shading – but he has a lot of lines in there to create texture and we’re mimicking that in the 3D process.”

From graphic novel to final shot.Prime’s main toolset involved Maya for CG work, rendering in V-Ray and compositing in NUKE. Everything was rendered in color but then in the compositing phase artists would de-saturate plates or make decisions about color, contrast and stylization based on feedback from the directors. “We’d do things like retain the color of the eyes or lips,” recalls Fangmeier. “Or a blue dress when one of the actresses walks into the bar. The blood on the faces was sometimes left in color and sometimes in high contrast black or white.”

Prime Focus’ approach to the stereo was to ensure it was actually part of the visual effects process. “The VFX artists worked in mono so they could work the way they were familiar with,” explains Prime Focus senior stereographer Justin Jones. “Then internally our stereo team were available to take the comps straight from the NUKE files and we’d run the stereo renders in our team and render any stereo passes we needed from CG. So it was a great hybrid approach of integrating our two teams together.”

Some stereo moments were derived from times when shots go in and out of the trademark graphic style. “It was really great to take that as a cue to drive the stereo,” says Jones. “If it was more graphical we could play it almost like a comic book you could cut out and put into depth. Also we would treat the realistic shots more realistically.”

Prime’s stereo toolset – known as its View-D process – revolves around Fusion but also uses NUKE and OCULA. The studio has also heavily invested on geometry mapping of actors and set pieces from the native photography, as well as comp’ing in additional elements for stereo effect (although unlike in most shows this was able to be during VFX production).

Frank Miller’s original frame and the final shot.Jones calls out two signature stereo moments as ones he is particularly proud of. “There’s a shot of Marv driving a car – it starts off stark black and white with graphic shapes and we kept that pretty flat and then expanded it as it transitions into a more realistic look. And then there’s a shot of Eva Green’s character diving into a pool. It’s flat as she jumps in but as soon as she hits the water it sends this ripple on a vertical axis and it comes towards camera, so being able to add stereo to that was great because it was unexpected.”

“Robert Rodriguez is one of those directors who really understand the stereo medium and can use it to tell the story,” says Jones. “He wanted to go bold with it and give the audience a lot of eye-popping experience – he wanted them to understand why they’re wearing the glasses.”

All images and clips courtesy of Prime Focus World and copyright 2014 The Weinstein Company.