Venom: Let There Be Carnage sees the return of the Marvel Comic character Venom. It is the second film in Sony’s Spider-Man Universe (SSU) and the sequel to Venom (2018). The film is directed by Andy Serkis from a Kelly Marcel screenplay, based on a story she wrote with Tom Hardy who stars as Eddie Brock / Venom.

In the film, Brock struggles to adjust to life as the host of the alien symbiote Venom, while serial killer Cletus Kasady (played by Woody Harrelson) escapes from prison after becoming the host of Carnage, a chaotic spawn of Venom.

The film’s extensive visual effects were supervised by Sheena Duggal, who also worked on the first Venom fim. For Venom: Let There Be Carnage , there were 1,323, VFX shots in the final edit. Shots and assets were primarily shared between an in-house team, DNEG, and Image engine. The Third Floor did Previz, and also shared some of the camera blocking.

Sheena Duggal is a long-time friend and supporter of fxguide, and she is well known for previous films The Hunger Games (2012), Body of Lies (2008), and the first Venom (2018).

The Art of Venom and Carnage

Duggal says from the outset, the film was blessed with incredible teamwork on the set “and one of the best crews I’ve worked with. Each project brings with it a different set of challenges, timelines, and budgets,” she explains. “It’s extremely important to work with the other departments in the pre-production stage especially on a big VFX feature, I feel so fortunate that we had a great crew on this film and that we were in collaboration with. Oliver our production designer, Jim in stunts, Joanna with costumes, as well as the actors, Kelly the writer, the producers, and last but definitely not least, our DP Bob Richardson.” Duggal was on set and very active with both the creative team and Tom Hardy himself. “Together we had a lot of conversations, walked through sets and action.” Hardy has been generous in his praise of Duggal. The actor had a challenging acting role requiring him to visualize fast-talking and arguing with Venom, a character he himself voiced.

The film didn’t use motion capture, everything was keyframe animation. The other alien creature was Carnage. How the character Carnage moved was explored with performance artists and onset there were creature performers who would stand-in for the character and give the whole team a basis for movement. “Ultimately, we worked with The Third Floor UK (TTF) to pre-visualize how Carnage would move and Image Engine and DNEG developed FX simulations that added another dimension to the way he moved and how the tentacles moved with him.” Christian Irles led the work at Image Engine, and Duggal has high praise for his VFX supervision.

It might be surprising that a film directed by Andy Serkis, one of the world’s leading exponents of motion capture, did not use the technology on this film. The Venom alien is not a direct re-targeting type of character, his body and face break normal law of biomass preservation and physics. Andy Serkis however, did do animation studies or facial performance reference clips for the VFX team. These leveraged the director’s strong acting as well as directing skills.

Duggal found ways to work the VFX requirements in with Tom Hardy’s acting process. For example, Tom Hardy would record the lines of Venom ahead of filming the scene and have them played back in his ear. Duggal would wait on set until Hardy settled into the space and then introduce a maquette where Hardy imagined Venom to be, and not the other way around. Thus It was Hardy who effectively worked out the imaginary blocking of Venom and then the effects team supported this and visualized it, for Hardy and the rest of the cast and crew. This allowed everyone to understand the space Venom would be added into later, so that they could react, light, and frame everything correctly on set. This is in contrast to many other films where the effects team tells an actor where to look. On Carnage, Hardy and Duggal worked jointly to provide this. Additionally, Duggal sat in the primary on-set video split tent to discuss with the Director and the Actor, motivation, performance and tone of the shots.

The film was to be delivered in August 2020, but it did not finish until September 2021 due to the disruptions of the pandemic. “The production, the crew, and the scheduling for our film got completely messed up by COVID, as most productions did,” says Duggal. “We started post-production while we were still shooting in San Francisco, so when we wrapped principal photography I came back to LA, and shortly after we all went into lockdown.” Duggal was supposed to be working in the UK with her production team and VFX producer Barrie Hemsley but due to COVID that didn’t happen. Due to the pandemic, the whole film was completed with the crew working from home in different countries. “My team remained in the UK and after about 4 months it became clear this was the new normal. I was able to build a small team here including a coordinator and VFX editors Roxy Dorman and Claudia Jolly,” Duggal explains. “I was able to continue to work with master DOP Bob Richardson. Bob is the consummate collaborator with visual effects because he gives us the most beautiful footage to build on, and I delight in his use of back light,” she explains. “He was very happy to see the key art we were creating and gave us his input. He was even able to come out to LA and grade the film with our colourist Elodie Ichter and myself a couple of times.”

Art : Visualising Carnage and Working Remotely

Duggal worked with The Third Floor “and their fantastic previz supe, Martin Chamney. We had thousands of artists working from home, to help get everyone on the same page. We extensively postviz’d every VFX shot in the film and developed key art and concept designs to show look and lighting intent with concept artists Adam Burn and Jeff Read,” explains Duggal. “Not only did this act as a first pass blocking for the vendors but it also helped the filmmakers and studio visualize the look ahead of the VFX being completed.”

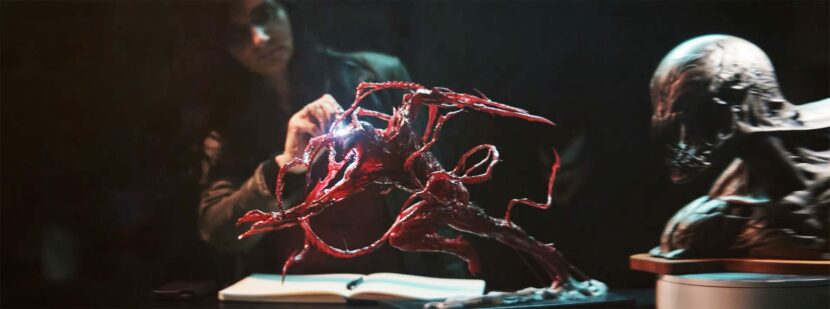

In tandem with the evolving concepts, Duggal decided that it would be beneficial to sculpt a maquette, “to give everyone something physical to interact with in the early days, rather than waiting for it to be built in CG,” she commented. “This allowed us all to see how the character was going to look. It also gave me something to do lighting studies with. I used the sculpture to create some images of Carnage with dramatic lighting which all the filmmakers loved and I was able to share with the vendors to show the lighting intent and direction.”

Due to COVID much of the project involved working from home across multiple time zones. The team used a variety of tools including emails, iMessage, whatsapp, Clearview, Evercast, Zoom, Aspera, Microsoft teams, Slack, Shotgun/Shotgrid, Q-take, PIX x2x, Moxion, RV, Cinesync, and Streambox. “Initially I didn’t have a server set up in my house. That, coupled with limited bandwidth internationally, meant it was hard to download directly from the server in the UK,” says Duggal. “I would spend hours downloading data packages from TTF, Editorial, Framestore, DNEG, the in-house team, concept artists and Image Engine and managing them on my laptop using only the finder. Humans are not designed for this kind of input so there needs to be smarter workflow solutions if we are working from home.”

The project was extremely demanding but the team did adapt thanks to persistence and practical intelligence. “I haven’t looked at this recently but by October 2020 I had read 22k emails and sent 6K,” comments Duggal. “That was almost a year ago so I can only imagine it’s triple that by now. For the 1,323 shots in the cut, the approximate number of ‘unique’ submissions I reviewed stands at about 35,000, however, if you include the number of actual submissions that included multiple formats that number reaches 54,259!”

The Science: L-systems

The Ravencroft sequence presented the interesting challenge of conceptualizing wraith Carnage, the Carnage transformation, and his increased biomass, as he deployed his tentacles and spawned in an L-systems structure to elevate his position above the asylum’s security personnel.

It occurred to Duggal there are a few places where the VFX team had subconsciously made the tentacles, symbiotic to the environment Carnage was in. For example, during the escape Carnage seemed to be mirroring his environment somewhat and Duggal liked how this worked. Similarly, when Carnage is up in the bell tower with Shriek, he had a very buttress-like look to him as if he was taking on the attributes of the cathedral.

This led Duggal to look into L-systems. Lindenmayer systems or L-Systems are popular in the generation of artificial life. The recursive nature of the L-system rule leads to self-similarity and thereby, fractal-like forms are easy to describe with an L-system. Plant models and natural-looking organic forms can be defined, by increasing the recursion level and the form slowly ‘grows’ and becomes more complex. L-Systems have also been used in architecture. From organic fractal forms, one can create structures and systems. Duggal found a research project by Miro Roman around a cathedral created using this idea which she described as “crazy but got me excited…as a possible solution for Carnage in the Cathedral.”

L-systems are a mathematical formalism for describing the growth of simple multicellular organisms, and with an L-system, you can encode a simple set of rules which, when applied iteratively, result in arbitrarily complex geometric structures. DNEG and Image Engine shared assets and created procedural FX passes that built on the concept and fed into their animation teams.

The project “Towards An Any Cathedral” below, deals with manipulating information (data), to generate a new object. Five High Gothic cathedrals were taken as the starting point of the project. Their geometrical and spatial characteristics (number of naves, the amount of light, the towers’ height etc…) were the source data. By using open-source 3D models of cathedrals, their basic geometry is appropriated and then a set of algorithms are defined which connect the default information into a new structure. The end result is an object that is entirely a product of mathematical and logical thinking. The object now becomes a product of pure intellect, grounded in history and culture. The images below of a real Cathedral generated the images in the video below them.

Below is not a collage, but a fusion of properties using L-systems.

L-systems were developed in 1968 by Aristid Lindenmayer, a Hungarian theoretical biologist at the University of Utrecht. Lindenmayer used L-systems to model the growth processes of plant development. L-systems can be used to generate self-similar fractals. L-systems were conceived as a mathematical theory of development. The geometric aspects were beyond the scope of the original theory. But there were subsequent geometric interpretations of L-systems in order to turn them into fractals.

Fractals often appear organic as they have recursive self-referential features at varying scales. “I really liked this creatively” commented Duggal, “But I think I did create a lot of difficult problems for Image Engine and DNEG to solve, particularly how to take this idea and make it scalable. But I do think that the recursive nature of the approach helped us.” DNEG and Image Engine worked on the development of Carnage. It required close collaboration between animation, creature and FX departments to build what would eventually become an incredibly complex FX simulation, requiring seamless integration with plate performances and digi-double elements, lighting and comp.

One of the complexities of the narrative requirements of the characters’ designs were the tendrils or tentacles and how these could support weight. Often they lift heavy objects and move massive props such as 1-2 ton car. By referencing the plant-like organic properties of large tree limbs, the visual remained grounded. Duggal and the team also had to avoid Carnage or Venom’s tendrils looking at all like a web, given the material’s relationship to Spiderman and his visual language. “We needed to violently grow these structures that were structurally sound enough to support these story points.” she adds.

The Science: Modified Facial Rig

The animation team was able to leverage the original Venom character design and lookdev from the first film. On this film, the team established how Venom looked using an approach that utilized a traditional character animation rig that was then enhanced with complex creature FX that produced tentacles, shields, goo, and detail around his eyes and mouth.

But the second film required Venom to speak many more lines than he had in the first film and the character animators had to develop Venom’s personality. Of particular importance was animating the dialogue that builds the relationship between Venom and Eddie. “We accomplished this by working with writer Kelly Marcel on set to understand the intention of her writing of the character and to incorporate that knowledge into our approach to the character,” comments Duggal.

In this film Venom has a lot more character and we see him in many more scenes. For example, there is a scene in which he uses multiple tentacles to cook Eddie breakfast and a scene where he and Eddie have a physical fight. “We hadn’t developed anything this extensive in the first film and this time around we leaned much more into the comedy of these moments,” says Duggal. “It was always a fine line to not fall into being too goofy with the performance of the characters.”

To get the range of dialogue the team at DNEG rebuilt the facial system completely. Duggal completely relied on DNEG to manage this process, she was across lookdev and animation tests, but the technical problems and facial rig were all solved in-house by DNEG. One of the problems with Venom are his huge teeth, plus he has a smile/mouth opening that goes all the way back into his skull and he essentially has no lips. DNEG had to find a way to give him expressive lips to allow lip-sync, and effectively add a version of eyebrows to allow the range of emotion the script required. They had to do all of this while not breaking the look of the character or straying too far from the first film. Even with these advances, the animation team used head position to convey emotion, using a head tilt or a tiny nod to provide subtext.

The Science: Muscle System

DNEG, led by VFX supe Chris McLaughlin, also updated the muscle system and improved on the first film by deploying a 3 layer muscle/fat/skin simulation. More weight was added to Venom’s animation as well as adding cloth interaction with his tentacles. Venom made an appearance this time in many more shots than in the first film, so the animation rig was rebuilt and new dev work had to be undertaken, as well as redesigning the charcacter’s connection to its host (which was not visible in the previous film). Extensive cloth simulation was undertaken to ensure that the connection between Wraith Venom (and Venom tentacles) and its host looked realistic and physically plausible. This work had to be done across multiple costume variants, all of which had to be built in a photo-real fashion.

Sheena Duggal also appeared in a Kai car TVC tie-in with the film. She did this in part as a way of championing the role of senior technical women in the film industry. Duggal supports more balanced gender roles and inclusion in Visual Effects. While the TVC is filmed on special sets and not the actual VFX sets or post suites, the Ad Agency wrote the script around Duggal’s own comments and attitudes trying to faithfully reflect her actual thoughts.