Many fxguide readers would already know the story of how Jurassic Park came to the screen. Indeed, the 1993 Steven Spielberg film is oft-cited as ‘the reason I got into the industry’ by countless VFX artists. From its innovative use of special effects supervised by Michael Lantieri, to the practical animatronic Stan Winston dinos and, of course, the incredible CGI creatures enabled by Dennis Muren and his team at ILM with the help of Phil Tippett – Jurassic Park is and was a milestone in the history of effects films.

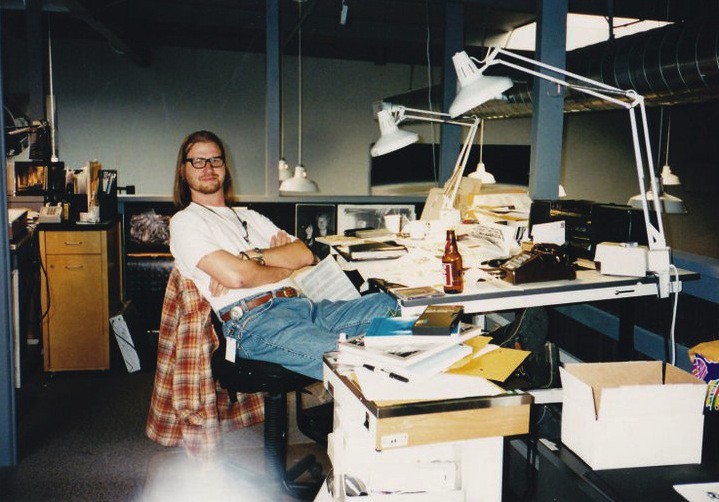

Now, with the imminent release of Jurassic Park in 3D, we revisit the creation of the digital dinosaurs with vfxshow regular TyRuben Ellingson, ILM’s visual effects art director on the show and now an experienced concept designer. And we also talk to Stereo D President William Sherak about the film’s 2D to 3D conversion.

Art directing Jurassic Park’s visual effects – TyRuben Ellingson

fxg: What did your role as a VFX art director at ILM involve on Jurassic Park?

Ellingson: Historically speaking, up until the very late 1980s, a core production team at Industrial Light & Magic was typically composed of three key personnel; a Visual Effects Supervisor, a Visual Effects Producer, and a Visual Effects Art Director. These individuals were the first to get to work on a show, typically interacting with the director and/or studio up front, and then staying with the show until its completion and the final shots where delivered to the clients. Along the way, other specialists, like model builders, matte painters, and/or motion control operators, would join the production to bring their talents into play, but this would be for a limited time frame with regards to the larger calendar of creating a film’s effects.

As work at ILM expanded the roll of CGI in their VFX pipeline, the roll of Computer Graphics Supervisor was added, and sometimes, depending on the nature of the work, an Animation Supervisor, or Animation Director. For the VFX Art Director, this full duration of involvement was subdivided into a number of assignments, the three primary being, concept or “look” design, story boarding, and something like, provider of unencumbered “aesthetic observation.”

This T-rex attack on the car made particular use of Stan Winston’s incredible practical dinosaurs.

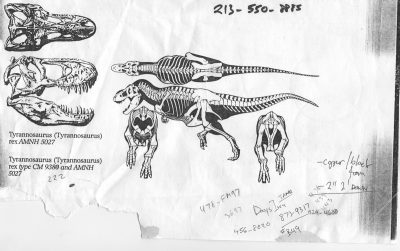

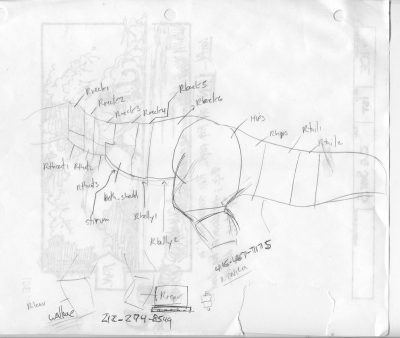

With Jurassic, the concept/look design assignments I remember was doing skin pattern color studies on some of the dinosaurs, providing some matte painting studies for some of the park’s establishing shots with dinosaurs in frame, and doing some digital composite studies for the scene in the film when, after the tyrannosaurs attack on the rainy roadway, the escaped rex pushes one of the park jeeps over the edge of a cement retaining wall, and it nearly crashes into Dr. Grant (Sam Neill) and Lex Murphy (Ariana Richards).

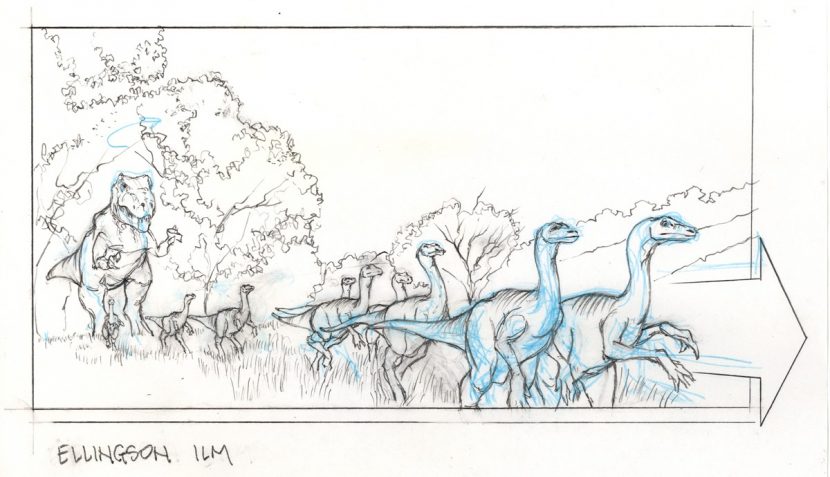

Creating effects story boards was an important part of every show an art director was assigned to. In those days, very detailed storyboards were worked up of each effect shot that would be created. In the beginning of a show, these would be generated from script pages and meetings with the director — often these were done as part of the bidding process, as these boards helped identify the approach ILM would employ to create an effect, the numerous elements likely required to execute that approach, as well as act as a shared document of intention between ILM and the studio. In the J Park days, the boards I did where first done in pencil, photo copied, and then tone rendered in gray design marker.

– Above: Watch a video on Stan Winston Studio’s sculpting work for the animatronic T-rex. There are other great behind the scenes Stan Winston videos available here, including on the raptors and Brachiosaurus. The incredible work of Stan Winston Studios is now being carried on by Legacy Effects.

After plate photography was under way, an art director would put the film up on a film viewer and carefully trace the details of the actual scene, and then add the “effects” into these in a manner that was much more informed (back in the art department, employing the same technique as described above).

Lastly, an art director would attend dailies every morning to provide creative input and reflection on the developing shots — to bring an unbridled “free to critique eye” to the process, one free of the technical demands of production.

fxg: What were some of the looks/behaviors/feelings you were trying to impart onto the dinosaurs ILM was creating?

Ellingson: Stating it simply, it was what I would call, “naturalistic realism.” And to take each shot to that realm, we developed a guiding set of principles, or put another way, “a bundle of refined understandings,” based on natural phenomenon and keen observation of present day animal behavior.

The very first meeting I recall attending back when word of Jurassic Park getting made was just a whisper, was held in the “D” building screening room, the larger of two such theaters located at the Kerner ILM campus. The group that gathered was fairly small, perhaps a dozen or so folks in all.

Dennis Muren was the person who invited us, and once the theater doors were closed, he had the projectionist to put up a reel comprised of clips from half a dozen or so films that featured dinosaurs. I don’t recall with high detail which specific pictures these were, as, over the weeks that followed, we often viewed clips from all manner of movie — clunky VHS tape piped though heavy televisions punched atop rolling carts — but I think King Kong was in the mix, and Valley Of The Gwangi — all stop motion stuff — I don’t recall any “man in a suit stuff.”

With the lights down and the footage silently flickering away, we all voiced our opinion about what was and wasn’t working in the shots, and what kinds of things, given the strides that were being made with computer graphics, could be avoided, enhanced, or totally reinvented. This commentary was not limited to purely technical concerns, much of what was discussed dealt with movement and animal behavior.

Next up on the projector was footage of an elephant, its limbs painted with lines and cross hatches at the joints, walking around in a parking lot — footage originally shot as animation reference for the AT-AT walkers featured so prominently in The Empire Strikes Back. This footage brought the conversation round to weight and moving large mass around — muscles and the movement of skin. People were focused, thoughtful, excited, and even in that early moment in time, it felt like this movie was going to be the game changer for CGI.

– Above: Jurassic Park filmmakers discuss seeing some of the first CG imagery created for the film.

In the weeks that followed, that core group, plus new several additions to the team, visited the local animal park and were treated to a private tours that got us up close and personal with a variety of critters. I shot reference photos and did my best to make careful mental notes of any animal “subtleties” I could identify and discern. In point of fact, I never imagined myself being so close — often within an arms length — to really big animals — rhinos, elephants, alligators, and giraffes — and though it was marvelous on many levels, I also found it unnerving and quite frankly, surreal.

I can’t recall with certainty if Phil Tippett and his key players participated in all of the above, but needless to say, they were part of the mix from the very beginning. In those early days of preproduction, Phil, his stop motion animators, and the ILM CG animators often entered into spirited conversation revolving around the possible pitfalls of, or ultimate gains, of animating the dinosaurs strictly with a mouse and monitor. I think it’s fair to say that Phil was deeply concerned about such an approach, and given his mastery of stop motion, considered this new “mouse driven form of animation” to be not only “abstract,” but out right inferior.

Putting it in a nutshell, I think Phil’s sense was it lacked a kind of “real world awareness,” or at least animators who came to the party with primarily a digital background, might not be able to zero in on the proper dimensions of dinosaurs performance. To address such concerns — along with wanting to do everything imaginable to break new ground with regard in bringing living dinosaurs to life — in the early weeks of preproduction, nearly everyone on the show began attending mime classes. Perhaps three days a week, just before lunch time, we all changed into our sweats and met in a carpeted storage space set up for these classes. Our instructor, who’s name I sadly can’t recall, a very inventive and thoughtful guy, would soon have us working through exercises that included mimicking other members of the group, stalking and fleeing from one another, and at times entering into robust mock battle. It was wild.

– Above: Phil Tippett supervised this stop motion animatic for the velociraptor kitchen scene.

As I was not an animator, I didn’t really feel compelled to take a stance on whether this proved to make a difference or not. But in my mind, it did expand the possibilities of what was going on, it made it all the more rare and amazing, and connected the group together in a manner that felt appropriate to the tasks at hand.

Of course there was much, much, more — Tippett Studio sponsored an afternoon of “beer and paleontologists” — the DID (Dinosaur Input Device) was constructed — new processors were brought online — offices moved — a full scale raptor was shipped up ILM from Stan Winston studios — I wish I had the time to write it all down.

fxg: There’s a famous test that ILM put together to show Spielberg of CG dinosaurs – just how did the CG dino test come together? What do you think it was in that test that convinced the filmmakers this was the right approach?

Ellingson: Stories about the early dinosaur test come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes — one of those tales that has a life of its own — my version goes like this.

In the very beginning, the dinosaurs in the film were going to be done with Go-Motion and/or stop motion. At the same time, it was clear that ILM’s “Computer Graphics Imaging” department and/or capabilities where really expanding quickly and were clearly very sexy. But that said, and this is a big but, to all but a very small hand full of people, CGI appeared to be, and was perceived to be total Voodoo. In an industry so large, and with such a well established approach to and/or understanding of production, the folks in charge of budget and schedule were all understandably nervous about about putting too many eggs into the CG basket.

So what happened to change people’s minds? From my perspective, it was actually two separate, yet interconnected things — two tests — one done clandestinely: the running Rex skeleton — the other, all above-board, a proof of concept test of a Tyrannosaurus chasing a gaggle of gallimimus.

The running Rex cycle was done by CG whiz kid, Steve Williams, with support and assistance from his friend and confidant, computer graphics supervisor, Mark AZ Dippe’. On off hours and between assignments, Steve had constructed the skeleton of a tyrannosaurus and animated it running at a very good clip. As it was digital, this allowed him to take full advantage of motion blurring, interactive shadows, and dynamic camera placement. The resulting animation was really very exciting, and gave a good glimpse of the creative potential that CGI would offer Steven Spielberg.

The exciting part of this story, the “outlaw” part, is that showing it to those in power at the studio was going to require Steve putting his neck out and just finding a way to show it without permission — which he did. My understanding is that Steve found out that the film’s producer, Kathleen Kennedy, was going to be on site, and somehow managed to share the run cycle with her. As for the details of how this happened, it depends on who you speak with, but bottom line, it made a big impression, and led to test number two.

This second test was designed and treated like a shot from the film. Dennis worked with me to create a storyboard of what we were shooting for and pulled together the team to get it done. The back ground plate for the shot was filmed up at Skywalker Ranch, and was really just a large clump of trees with some tall grass in the foreground.

The T-rex chases one of the vehicles. Steve ‘Spaz’ Williams crafted the animation, even studying the run sequence backwards to look for ‘mistakes’.

Simultaneously, modeling got under way on a “skin on” tyrannosaurus and gallimimus. Over a couple of weeks, the dinosaurs were texture mapped, animated, composited into the plate, and the entire thing output to 35mm.

The end result?

Stunning.

Even without refined secondary animation and refined texture mapping, it looked really amazing. And projected? Wow. It was awesome.

That screening with Steven in LA changed the course of the picture, and though it was still unclear how many shots could be produced in the allowed time frame, or really how close the digital dinosaurs could be brought up close to camera, the strategy of using stop motion in the show entirely went away.

What went on from there? A great, great, deal.

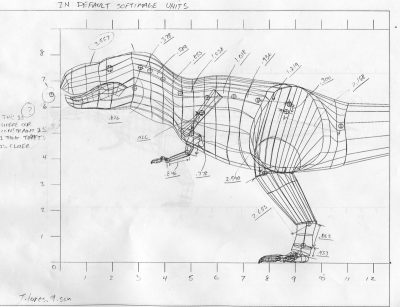

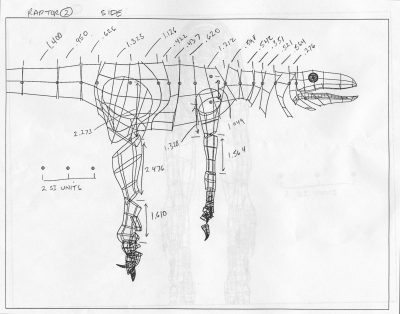

fxg: Can you talk about some of the tools you were using at the time, both for designs/boards but also completing say CG texturing?

Ellingson: With regards to my work on the show, as I hinted to above, most of my work was done in a very traditional manner. Story boarding on paper, doing some key frames with marker and colored pencil, this was how the infrastructure of the facility was set up, and this was the quick rout for getting things done.

I was involved with creating early texture maps for a number of the dinosaurs (in point of fact, I did them for the sanctioned test described above), and for these, I worked with a very simple paint interface that was developed for the ILM pipeline. It was extremely limited, a brush tool, a smudge tool, and a funky pencil tool that I don’t recall ever using for anything, but it did get the job done. There were often crashes and freezes — whenever there was a thunderstorm, the VFX producer, Janet Healy, would scurry from room to room shouting, “save, save, save!” It was wild.

– Above: Rick Carter, Dennis Muren, William Sherak, Phil Tippett and Martin Ferrero discuss the making of Jurassic Park at the Academy’s April 2, 2013 screening at the Samuel Goldwyn Theater.

fxg: Any special memories or stories from your time on Jurassic Park?

Ellingson: At some point during production, after we were getting plates and shots blocked out, conversation arose concerning the stampeding gallimimus sequence, specifically the moment where the frantic animals leap over a very large fallen tree. I don’t recall how the idea came up exactly, likely because of the mime classes I mentioned earlier, but the notion of shooting some reference footage of a group of Jurassic Park personnel running and leaping over a scale version of the fallen tree might prove to be valuable for the animators assigned to that shot.

To pull this together, as art director, I worked with the model shop to get some large plastic pipes delivered and supports constructed to hold them in a configuration that matched the plate photography. This was all set up on one of the parking lots, chained down and sandbagged to keep things sturdy, and then a small camera crew set up the shot to match the lens and reference.

Watch the gallimimus sequence.

When afternoon arrived, we all gathered on one side of the pipe, stretched out a bit, and prepared to get our leaping gallimimus action on. Now, these pipes on their stands where actually quite high off the ground, perhaps three and a half feet. Getting over them was going to mean a speedy approach and good amount of life when one jumped. This being the case, it didn’t seem that difficult, at least from an athletic perspective.

ILM digital compositing innovations

There were several advancements made in the field of computer graphics by ILM for Jurassic Park. But the studio had also been striding ahead in digital compositing. vfxshow host Matt Wallin interned at ILM in 1992 while he was still in college and while Jurassic Park was still being completed. He gives fxguide a run-down of the comp tools in use at the time.

“Compositing was done using a text based compositing system (no GUI) that was called HostIP by those using it. It was essentially a Header script which had several built in lines of code that could be turned on and off to call various images and sequences and then tweak them with image processing algorithms. It was pretty clunky but got the job done and in some cases was a great way for people who had been used to optical compositing to understand the core processes involved in the digital realm.

The same system was used on T2 and stayed in heavy usage for a number of years. I used it on my first comping show at ILM, Twister, some years later, but we switched compositing tools on that show over to an in-house GUI that was written called iComp. iComp was later replaced with a folder based GUI that was a lot like AE called CompTime.”

However, this was me preparing to run and jump, a dude who never played sports, no basketball in high school, not a skier, bicycler, or bowler even. I spent my time sitting at a desk, my weekends tipping beers, and watching movies, other than strolling to the corner between builds to make copies, to get a coffee, prancing and leaping was really something done only in my childhood. But…this was Jurassic Park, and it was all so very ground breaking. A superior dinosaur mind set would show me the way.

Roll camera, take one. Not bad, we all hit our marks, perhaps fourteen actors in all, cutting and jockeying for position as we approached the plastic log… But damn… It was a steep jump.

Roll camera, take two. I’m in the zone, working my approach with the jerky movement of a scared pray that I was… Then I cut towards the center of the group, only to lose speed behind so many other frightened comrades. I’m at the rear of the pack, I can feel the massive rex gaining on me… The log ahead of me clears and I jump! Not good, not high enough. My foot catches and I find myself pile-driving towards the asphalt ground below, my feet still hung up on the log. I swing up my arms, reach out to soften my landing, protect my head with only micro seconds to spare… Snap.

Snap and tumble.

Yes, I have broken something… No, I have shattered it. The elbow of my drawing arm. You will be eaten, sad Mr. Bad Leaping Gallimimusaur.

So, off to the ER. Surgery is required — bone chips removed — Radius bone clipped clean with the aim of letting scar tissue develop into a kind of organic rubber band which would not hinder the movement of the remaining Ulna bone and joint (which did eventually happen).

My only thought through all this? Please don’t let this affect my credit, put me back in the game, coach (funny sports analogy from the self described non-sports guy).

But, with regards to Jurassic Park, something interesting did come out of all this. When Phil Tippett heard what had happen, he said, “well, then one of the Galli’s is going to need to take a fall. If it happened to Ty, it would likely have happened in the wild.” And that’s just what you will find in the film. If you watch close, as the group of frightened gallimimus go running and leaping over the log, one does indeed fall to the ground. Unlike me, after scuffing up patches of grass, it does scramble to its feet and continue out of frame.

A prefect example of “naturalistic realism.”

3D dinosaurs in 3D – William Sherak, Stereo D

fxg: Do you remember when you first saw the film?

Sherak: It was the summer I graduated high school. It was amazing, right? It was the first movie ever where a CGI character was the main character, and I thought, ‘Oh my God we’re seeing the future of Hollywood!’ And then when you get a call 20 years later to say, ‘Hey you want to work on this movie, there are no words to describe what that’s like.

fxg: Where do you start with converting a seminal film like this?

Sherak: Basically we got a call to say Steven would like to dimensionalize Jurassic Park. In a similar process to what Jim Cameron had gone through with Titanic – I think that was our entrance because of what we had gone through there – there was a comfort level there that we would be capable of accomplishing what Steven said. We sat down with Steven and Amblin, and the first thing we did was watch the film and talk about what he wants.

Imagine that first meeting – you’re sitting in the Amblin screening room and in walks Steven Spielberg and you get to watch Jurassic Park with him, and talk about what he wants out of the 3D. That was the first real meeting. We watched the film on silent and talked about pretty much every scene and what he likes in stereo, what he doesn’t and where he wants to really feel immersed.

See some of the work behind Stereo D’s conversion of Jurassic Park.

fxg: How was Jurassic Park prep’d for conversion?

Sherak: We took the original 1993 35mm O-neg, did a 4K scan of the picture. We did a full restoration on the image, and a full color-correction. Steven really wanted to match the original look – the color is very similar to the original. Which means you watch it and you have this brand new experience but you don’t feel like you’re watching a different movie. It’s the same cut you saw in 1993 but we just dimensionalized it.

fxg: Can you talk about some of the challenging conversion scenes, say the T-rex paddock in the rain?

Sherak: You mean, our nightmare…? It was the biggest challenge our studio had to face – we wanted to get it in front of Steven straight away on a shot basis. It’s not just rain. You have foreground rain, then you have reflections on the windows, then people inside the car, then you have the other window because he shoots through the car – reflection on that second window. Then you have rain on the other side of that window. Then you have the bars of the fence, then the leaves of the trees inside the paddock and then the T-rex. So the foreground rain was actually the least problematic of the whole scene!

Literally you start with rotoscoping every single thing in the frame. Then it’s about placing depth properly with how the human eye would naturally see depth reflections off glass, making sure you have the right internal volume of characters inside the car – the kids especially. Then when the dinosaur shows up behind the fence, you have to make sure you don’t hurt the scale of the dinosaur – it has to be a gigantic monster that’s as dangerous as you need it to be.

We also added a bunch of 2D rain elements. We rotoscoped each drop and then added a visual effects rain layer to give us more foreground rain.

On the other hand, the kitchen sequence with the velociraptors was a sequence shot with so much depth that it was creatively easier to assign depth to it, because it was almost shot in 3D. Just from a perspective standpoint you knew exactly how far everything was from each other. The shots are long and give you time to really know your environment.

All images and clips copyright © 2013 Universal Pictures.

“We took the original 1993 35mm O-neg, did a 4K scan of the picture. We did a full restoration on the image, and a full color-correction. Steven really wanted to match the original look – the color is very similar to the original. ” – BAM, right there. We can put our crazy theories and placebo to rest. Jurassic Park did get a 4K remaster, which is WHY it looks MILES better than the 2011 2D Blu-Ray, along with the warmer colour grading matching the 1993 trailer, etc.

I just came back from an IMAX 3D showing and the quality was stunning. I think it’s really wrong of Universal to even re-release the 2D blu-Ray on the 3D combo pack, not including the remastered 4K version, but the same old transfer used since the DVD release, artificially sharpened to death. Many people have sent their concerns to Universal but their “replies” have been nothing but useless and automated. Everyone shared their replies and got these: http://forum.blu-ray.com/showthread.php?p=7073921#post7073921

The first time:

“The 2D Blu-ray and DVD releases to be included is our upcoming “Jurassic Park” 3D package will use the master that was created for the Jurassic Park Ultimate Trilogy in 2011.

We hope that you will continue to enjoy our releases.

SIncerely,

Consumer Relations

UNIVERSAL STUDIOS HOME ENTERTAINMENT”

The second and onwards:

“The 2011 “Jurassic Park Ultimate Trilogy” Blu-ray release is based on remastered source material developed under the auspices and with the direct approval of the filmmakers. Extensive efforts went into the remastering process, and the differences between this Blu-ray release and our original DVD release are dramatic. The same remastered materials will be used for our upcoming DVD and 2D Blu-ray release.

We will forward your comments to the appropriate department.

Again, thank you.

Sincerely,

Consumer Relations UNIVERSAL STUDIOS HOME ENTERTAINMENT”

We want to take home this remastered experience not only for the 3D audience but 2D as well. To think that most of us who grew up with this movie payed for the movie tickets, VHS, Laserdisc, DVD and even the atrocious Blu-Ray copy – AND the again paid for the movie tickets 20 years later, deserves this.

Ian Failes I appreciate this article deeply and enjoyed it. If you can somehow forward this to anyone at Universal or Spielberg himself even, let them know we want a 2D copy of the same remaster from the 3D version. Contacting Universal’s customer service is kicking a dead horse at this point.

Just saw the 3D version more because I wanted to see the movie in a theater again than out of 3D-affection, especially when it comes to converted 3D. But I have to say, this conversion really reduced my scepticism on 3D conversion to great extent for two reasons: On one hand, this is just a very good movie to turn into 3D with a lot of neat and effective fore-, middle- and background compositions and Dean Cundeys beautiful tracking shots all over the film. And on the other hand it was skillfully done. My favorite shots in this version for some reason were the details of the mosquitos in amber on Hammonds walking stick and in the amber mine in the beginning.

Pingback: Jurassic Park | Jurassic Park

Pingback: Welcome (back) to Jurassic Park | Andymatic

Pingback: 8 Visual Effects That Changed Cinema Forever!