At the 17th Annual VES awards, Matthew Sandoval, James Ogle, Nick Keller and Sam Tack won Outstanding Model in a Photoreal or Animated Project for their work on London, in Mortal Engines.

While the film did not win favour with the critics, there is no doubt that the complex moving London model was one of the most complex, difficult and detailed models that Weta Digital has done, and fully deserving of the award. The city is complex, being part city, part vehicle. In fact, the category would have excluded Mortal Engines’ London if it had been only a city, even if modelled as one single model. Importantly, in this category the model is considered as a finished whole not just the underlying 3D modelling. The award is based on a combination of artistry, detail, textures, animation and lighting.

Mortal Engines was directed by LOTR veteran Christian Rivers. The film was adapted by Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh and Phillipa Boyens from Philip Reeves’ novel. We were able to speak to Ken McGaugh, Visual Effects Supervisor, and Dennis Yoo, Animation Supervisor, about the film and the building of London.

Mortally Complex Engines

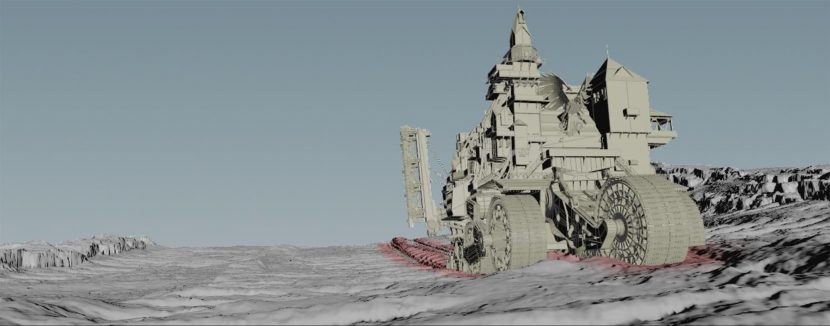

CGI was the only option for the enormous London model. “Given the scale of these cities, it was completely uncharted territory…wherever possible, I like to get things on camera, but obviously with giant moving cities on what would feel like completely alien terrain, you can’t get that much on camera,” commented McGaugh.

To secure the suspension of disbelief, the modelling team had to overcome a series of inherent issues. The model needed to look huge, a complex and detailed city, and yet it needed to move at close to 300km per hour. “Here at Weta, we have a whole workflow, special methodologies and tool sets for building environments in urban environments – but they all operate in the assumption that what you’re building and dressing doesn’t move,” joked McGaugh. The London model was designed to be 860 m tall and some 2,500 m long, eyt the movie opens with it chasing a smaller city at high speed. Any large moving object, filmed in the real world, tends to appear to move slowly and yet in cinematic terms, London had to be fast and aggressive.

Weta Digital delivered 1,682 shots, of which 378 were fully digital, such as the wide shots of London.

The team did extensive testing, as McGaugh comments, “Christian Rivers is a previz person himself. He has a lot of experience and he did a lot of it directly and what he didn’t do directly, he was very hands on in directing.” The difficulty with the previz is that the shots were animated ‘to camera’. Behind the scenes, this means the actual speed of London varied greatly. One of the first things the team at Weta did was unify the speed of London to around 300km/hr while still keep the energy in the shots.

Weta has tools for animating vehicles, but vehicle models tend to be very light weight in modelling complexity. What they needed was new tools that would allow their animators to animate London as if it was a vehicle, but still allow them to use a lot of their environment dressing and building tools in conjunction with it. Weta ended up building a new pipeline based around these things called hierarchical layout puppets. “They’re puppets, so we can build a vehicle puppet out of it, but they have all these points on them where you can attach environment layouts and this allowed us to work in parallel a lot better,” commented McGaugh. It allowed the animators to approach London as if it was a traditional character or vehicle.

Prior to this innovation, If one thing changed, then the team would have to recreate all the data for everything. The old traditional puppet pipeline did not allow for someone to just update one little thing and then carry on. The new approach allowed this. “We really needed to be able to break things apart,” explained McGaugh, “London’s design was based off of these lily pads on suspension systems, which automatically gave us a modularity to the design. Each lily pad ended up being its own asset. Initially it was a small urban environment with parks and benches and boulevards or buildings, and so then we just scaled that up.”

With these gigantic complex cities needing to move, “we had to jump the gun. We needed to move these assets while they were still being worked on,” explained Yoo. “That being said, the layouts were extremely heavy. So we devised a different type of process where we used our new skinny technologies called Koru.” First used on War for the Planet of the Apes, Koru takes the calculated geometry from Maya. It pulls that data out, converts it into a streamlined process and then it puts it back in a much quicker data form. “It works much faster than Maya and can calculate those sorts of things. And so it streamlines the process and it makes our files so much faster,” says Yoo. “With the drawing of geometry using our layout puppets, we went from 2 fps to over 50 fps with the London asset – the process just skyrocketed, and that was the only way we were able to animate those shots.”

The big problem Weta had was that after they added a tremendous amount of detail into these layouts, the rendering was near impossible. “London is, by far, the biggest renderable asset we’ve ever created,” he concludes.

To render London, the Weta render team resurrected some technology that was originally developed for The Hobbit called Cake. This is an intelligent appearance and geometric detail baking system. It bakes detail into a hard core data format that can be easily streamed off of disk at just the right resolution needed for rendering. “It also creates lower levels of detail without having to require the team to manually go in and make different levels of lower detail,” says McGaugh. “Everyone’s probably familiar with brick maps, the RenderMan Brick Maps – well this is a similar concept. It’s just a lot more intelligent as it actually takes appearance modelling into consideration as well.”

The set dressing was a key way to add both scale and detail. Wherever possible Weta would dress in moving cloth. For London this also meant adding in little atmospheric elements, such as steam and smoke coming out of pipes. In the lower tiers, where it’s a little bit rougher, they had the Londoners hanging out their laundry. There was also a lot of foliage on London higher up, and the team always added movement to the foliage. “Obviously we couldn’t make it look like if the foliage was being hit by 300 km per hour winds, that’d be a bit distracting, especially considering all the footage of the people on the exposed areas,” comments McGaugh. “The people had some wind on them, but we tried to keep it from being too strong and distracting.”

To give the model scale, the team naturally worked closely with lighting. “We have some new technology in our Manuka renderer that does physical atmosphere simulations, but it’s too expensive to do on a frame by frame basis and it doesn’t support clouds, which we had,” says McGaugh. As a result, on every single shot the team made a habit of rendering out some sample frames using a fully physical atmosphere in Manuka. This would give the team what the correct, or plausible, atmospheric perspective on London, as well as exposure values for the shot. These we’ve then used as reference frames in the composite. Most of the times the team backed off from the technical solution as “it was quite ridiculous how hazing things could get,” McGaugh explains, “and so we had to work to keep London looking exciting, interesting and pretty – and actually be able to see the ground at all with all the dust and atmospherics.”

The details on the CGI model were reinforced by the special effects team on the London sets. They rigged all the items such as hanging lamps, chandeliers and display cases with wires to imply they were all moving. Even the reflections were enhanced to seem like they were reflecting a moving sky or exterior.

Often it is left to the effects team to try and add detail to see scale so the model seems huge in shot. As any huge structure such as London would always be in focus, there were a set of approaches the team could apply to imply scale. The team used depth cueing with distance haze, and layers of high frequency fine detail, especially in the chase sequence that opened the film. “We had to find just the right sweet spot for how big the dust gets kicked up and how fast it shoots out and evolves,” comments McGaugh. “We looked at a lot of Dakar car rally footage to see what big dirt trails look like. We realized that people are used to seeing this footage, whether it be on TV commercials, or movies. Given this perspective, the team worked hard to make all the elements of the chase scenes seem relative to the size of the things chasing each other, in a way people were used to seeing, at the kind of speeds people are used to. “We had to make sure that it fell into that zone, so the audience believed it was an exciting chase, and maintain a balance to keep people from going, ‘wait, what’s going on here? This is just not realistic at all’,” he adds.

Movement is Life

London was always moving and so even in closer up shots of the city, it was important to always animate the city, even when the shot did not see the ground in frame. The team came up with an approach of adding little wispy clouds or textured air, that the director called ‘moving wispies’, to help remind the audience even subliminally that London is moving.

There was significant innovation in how London was animated as well. There was new innovation in allowing proceduralization of the animation of London (and the other vehicles) over uneven terrain. These included adding some secondary wobble to parts of the model. This allowed Weta to very quickly get animations turned around. When the blocking was approved, the animation team would do all the refinements and secondary animation. But the new approach got a fairly sophisticated animation as a first pass.

For secondary animation, Yoo was keen to do something different with London in this film. “I didn’t want all the animators to have to worry about key framing every single building for secondary motion,” he explains. “We devised a dynamic caching system for animation, to help with dynamics in animation.” Normally when animating with a dynamic system, the animator can easily play it forward, “but you can’t actually scrub it backwards unless you cache it. And the caching system was always a bit clunky. We devised a new system that caches quite quickly,” he explained. “This meant that scrubbing backwards wasn’t really a concern. We changed the cache system so while we were animating, we could now always have a visual cue of what the dynamics were doing in reverse, as well as forwards.”

This secondary motion of cloth or smoke stacks worked as an extension of how the uneven terrain proceduralization example above was implemented. The animators would take London, animate it the way they liked, and then turn on the dynamic system to create a first pass of secondary motion procedurally. The secondary motion on the buildings could be dialled in or out. When the animator was happy, they could bake that onto the puppet.”

The animators handled London a bit differently from the other moving towns or cities in the film. “London being so much bigger than the other cities, we realized it’s scale was so immense that adding too much secondary motion started making it look small again,” explained Yoo. In the end, the team dialled back the secondary motion, as “we actually made it feel more like a monolithic just plowing through the earth. The smaller towns when they move, are moving with those tracks and are going up and down – but London literally just plows forward through any sort of terrain.”