Jumanji: The Next Level reunites the four teenagers who survived the trials of Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle (2017) as they return home from college for the holidays. After Spencer is compelled to go back into the game, Martha, Fridge and Bethany must team up and re-enter the world of Jumanji on a daring rescue mission to bring Spencer home. But the game is broken and is fighting back. Everything they know about Jumanji is about to change, as they discover that there’s more to it than just a jungle; it’s now bigger, more dangerous, and has more thrilling and complex (VFX) obstacles to overcome.

Back in play are the avatar team of Dwayne Johnson as Dr. Smolder Bravestone, Jack Black as Dr. Shelly Oberon, Kevin Hart as Mouse Finbar, Karen Gillan as Ruby Roundhouse, and Nick Jonas as Seaplane, plus new players Danny Glover as Milo, Danny DeVito as Grandpa Eddie, and Awkwafina as a new avatar, Ming. This film was once again directed by Jake Kasdan. Mark Breakspear was the overall VFX supervisor. The film’s star and producer, Dwayne Johnson, knew how high expectations were for the sequel. “The scope and the scale of the film are really epic; when it’s Jumanji, it commands that. We went into this knowing that the pressure was on, and we’ve got to raise the bar. We’ve got to level up. So we brought in the best filmmakers and the best in class with all our department heads and our crew. Also, what’s really cool about Jumanji is we have no constraints because it’s a videogame.”

The visual effects ranged from a herd of attacking ostriches to hippos, giant anacondas, horses, camels, and some very unhappy mandrills. The visual effects artists were from around the world, with over 5,000 artists working tirelessly at various VFX houses, including Los Angeles, New Zealand, Montreal, Vancouver, and Melbourne. “I’m in the very fortunate position of being able to make outrageous requests that then a team of geniuses all over the world have to figure out how to actually execute. And on this movie, we had an absolutely staggeringly great group of people working on animals all over the place,” says director, Jake Kasdan. The VFX houses included Sony Pictures Imageworks (SPI), Weta Digital, Rodeo VFX, Method Studios (formerly Illoura), and Crafty Apes, plus some others did over 1900 shots for the movie.

The concept designs for the various new animals, such as the ostriches, the mandrills, camels, giant anacondas, horses, mandrills, and hyenas were initially done by Weta Workshop in New Zealand.

Ostrich Attack

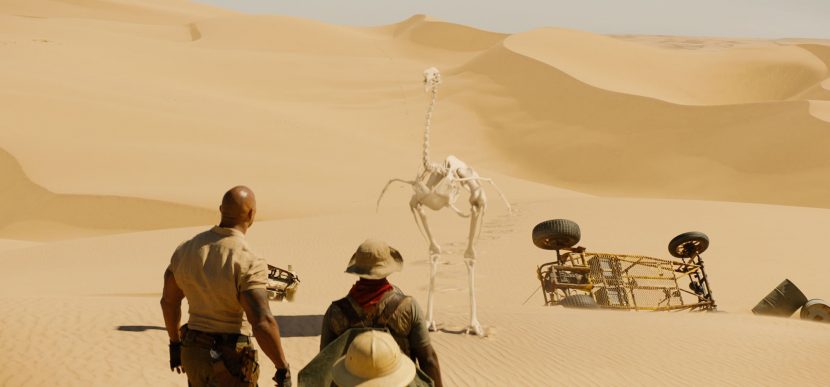

The ostrich sequences was done by Sony Pictures Imageworks (SPI), spanning from when we first see the ostriches until our heroes (almost) jump the gorge to escape the attack. “At first, one comes over, and Dwayne Johnson is like, ‘It’s just an ostrich!’ Then, over the horizon, thousands come towards them. They turn around and they jump into these dune buggies, and just take off with these ostriches chasing. They got these huge heads that can smash into metal! And they’re just…basically trying to kill them,” says Breakspear. “We’ve researched the whole thing. When I was in South Africa on another show, I went down to the Cape, and these ostriches were just running around there – and I got chased by one! I know the fear of being chased by a bird that’s twice my size. So I feel very personally attached to this sequence.”

The ostriches, much like most animals in the game, are not the exact same as their real-world equivalents. The Jumanji birds are more threatening and have a different head than their real-world equivalent. But they do share the same high speed over land when they run, as real ostriches are incredibly fast, due to their very long legs and thus large gait. Being able to step so far in each step provides real speed, but it somewhat masks how fast the birds are actually moving. This problem was present in the digital ostriches. While the motion over ground was the correct speed, the herd of birds did not seem to be moving quickly. SPI and Breakspear solved this by making sure that all the birds were running out of sync in the wide shots, thus the audience is always seeing the bird’s feet hitting the ground, and the apparent slowness is removed. While one bird seems to be running slowly”we made sure there were different feet falls in every frame.

The ostriches, much like most animals in the game, are not the exact same as their real-world equivalents. The Jumanji birds are more threatening and have a different head than their real-world equivalent. But they do share the same high speed over land when they run, as real ostriches are incredibly fast, due to their very long legs and thus large gait. Being able to step so far in each step provides real speed, but it somewhat masks how fast the birds are actually moving. This problem was present in the digital ostriches. While the motion over ground was the correct speed, the herd of birds did not seem to be moving quickly. SPI and Breakspear solved this by making sure that all the birds were running out of sync in the wide shots, thus the audience is always seeing the bird’s feet hitting the ground, and the apparent slowness is removed. While one bird seems to be running slowly”we made sure there were different feet falls in every frame.

The groom was not easy, due to the different scales of the feathers and the initial ostriches that were seen in the trailer being completely discarded and rebuilt for the main film shots. “SPI did the first ostrich CG build and this allowed us to get material done for the trailer but they then turned around and said ‘we need to rebuild the whole ostrich because we just literally bolted this together to get the trailer shots done’,” recalls Breakspear. “The ostriches we had worked for the trailer shots and nothing else. So SPI went back and rebuilt and redesigned them so their feathers had their own dynamics and the artists could control it. The environment was meant to be windy and we always wanted the wind to be blowing through the feathers and for them to feel alive.”

SPI used Ziva for the ostrich muscle simulations. Breakspear explains, “The realism came from the muscle sims on their giant chicken legs. If you look any of the early SPI renders of the ostriches with no feathers running it’s quite hilarious. It was like our heroes were being attacked by a whole bunch of uncooked turkeys.” From the Ziva sims and walk cycles, the team also generated all the footprints, dust and sand interaction. The feather sims were complex, as the birds are always flapping their wings and they even use their wings to help with turning and balance while they are running. “And then you have to render them with complex subsurface scattering going through the feathers and the light interacting with their fan (tails). So each one of these shots was pretty massive and SPI had their work cut out for them,” he adds.

SPI also had to deal with the location not being a closed set. The team was filming in a National Park and as such not only did the artists need to remove any crew footprints and vehicle tracks but, “we couldn’t lock down the location so there were Dune Buggies trolling us onset,… we’d just have to wait for them to go,” explains Breakspear. “There were people on dune buggies just riding through shots with ‘Trump’ banners – if you can believe it?! We actually had a shot where there was a whole procession of Dune buggies that came through with ‘Trump 2020’ banners!” All of this and the tracks they left behind were digitally removed. Another problem for SPI was the changing nature of the dunes. With the wind, the dunes move constantly and so the location effectively changes day to day. “Over the course of 3 days the sand can move 20 feet to one side”, Breakspear points out. The wind caused the production to shut down at one point, as the wind was producing a ‘sandblasting’ effect that was dangerous for cast and crew and would have ruined the camera gear.

Mandrill attack

“The mandrills were great to do, very menacing. As opposed to the ostriches, which were a bit more slapstick in nature, a little bit more fun,” Breakspear explains. “The ostriches are slightly goofy, they don’t really have teeth for example. They look kind of ‘dumb’ and they work as a mass group, they don’t work individually. Whereas with the mandrills you always feel there’s an intelligence behind their eyes and they individually want to mess you up.” The Mandrills were produced by Weta Digital, “because in my mind,” says Breakspear, “there was going to come a point, somewhere down the road, where someone was going to say, ‘these monkeys aren’t looking good. How come you didn’t go to Weta?’ And I just wanted to avoid that whole conversation,” he jokingly remarks. “Ken McGraw, the VFX Sup at Weta, was amazing to work with. Weta did the Mandrills and the bridge… I joked all through the production that I went to Weta for their famous ‘bridge’ VFX work and I was just pleasantly surprised to find out they did primates as well!” Weta also did the hyenas and other smaller sequences such as burning village at the beginning of the film.

The problem that Breakspear found immediately was that the actual Mandrills, in real life, almost look fake or computer-generated. Their fur around their face, for example, has a very fine fir or hair crimp which produces an odd specular reflection property.

Breakspear explains the painstaking work that goes into creating the visual effects: “For every second of the big visual effects shots you see, it’s been worked on for months and months of people’s time. People at these companies work on a single shot. You might see it go by like that; they’ll work on that for six months just so they can bring that to you and make you just amazed at what you see.”

Weta also did the hyenas and the burning village seen at the start of the film. “All teams I work with, they are special. They are really amazing people,” he says of this group of artists and digital wizards. “The needle’s at 11 – it really is. The people that come and see this movie want to see the best. And visual effects planned on delivering.”

Rodeo FX

Breakspear was particularly impressed with some of the smaller companies he worked with. “When you go to the major effects houses you know you are going to get brilliant work and we did, but some of the smaller effects houses such as Rodeo FX, “They had a lot of shots but in loads of different sequences. They had a lot of environments, they built the CG camels talking, and a whole bunch of environment shots when our characters jump into the water and transform back into their roles,” recounts Breakspear. “They did a bunch of the Oasis shots in the desert, the hippo, a bunch of extra CG horse shots, the Ice Wall sequence… they massively impressed me. I mean everybody was impressive. It is hard enough to do a big body of work around one animal, but when you have the same amount of time, but you’ve got small numbers of shots around lots of animals,… and they all have to look as good. It was really tricky. They really did a really good job.” The Rodeo FX crew was lead by VFX supervisor Alexandre Lafortune.

To illustrate the point, Breakspear tells the story of a shot that would never normally get much attention. It was a wire removal shot, but it went directly across Karen Gillan’s face. “A lot of companies would ship that shot off to India, get it done, maybe there is still a little shimmer somewhere and as a supervisor, you know perhaps if we add camera shake, or whatever… but you have to move on and it is what it is,” he explains. “But what came back to me as a VFX supervisor from these guys was nothing short of magic. They just kept refining and refining and refining. They were never happy until it was better than even I wanted, that to me is a sign of a company that is very stable in its design and its desire to do a good job, and it came across in everything.” Rodeo FX had previously worked on the first Jumanji film. Rodeo ended up doing 361 shots for the new film with a crew of 200 artists.

This commitment to project, even on shots that were never going to make someone’s showreel or win awards was even evident in the company’s effects notes. For any VFX film notes are attached to the shots that are sent to be reviewed by the supervisor. “Sometimes companies just state on the slate: ‘updated effects’, but Rodeo’s would be more like a ‘War and Peace’ novel about the battle that they’d been having with some aspect and then how they solved it. I read their notes every single day. It wasn’t massively long, but it was long enough so I understood where they were at, what the struggle was, and how they fixed it… they are a company of very passionate people.”

The majority of the complex horse work for the new character Cyclone was done by Method Studios in Australia. The VFX Supervisor was Glenn Melenhorst. This work was complex not only for the need for realism but for the surprising reveal that Cyclone could fly. Method Studios also did most of the third act of the film with the mountain fortress attack and the hot air balloon (blimp) sequence.

One other smaller team that Breakspear enjoyed working with was Crafty Apes. “In a movie like this you need a lot of temp shots and post-viz”, he explains. The team did over 700 temp shots for the film to help with editorial and approvals. ” Crafty just kept helping us out wherever we needed it. They just helped us massively. I was really impressed with them. I am definitely a fan of theirs for the future”.

Actor Scanning

For many of the sequences, the action required the use of digital doubles. Breakspear organized for a master scanning session on set, which was then given to all the vendors who needed the material. “Josh Hakim (Industrial Pixel) was brilliant,” says Breakspear. “He got it done so we could scan somebody in about eight minutes. Which is nothing, it took longer to persuade our actors to get in that booth to be scanned, than it did to do it,” he jokes. In the end, all the actors were happy to do it, especially the younger actors, for the more experienced actors such as Dwayne Johnson, he had been scanned many times. Breakspear actually first scanned him for the film Journey 2 :Mysterious Island (2012)

Josh Hakim was in charge of the actual scanning of the actors using his company’s mobile scanner. Hakin is head of Industrial Pixel. The Vancouver based company’s Structured Light Photogrammetry Capture (SPC-HD) rig was developed in-house as a portable and yet complete scanning system for large and small productions. The rig can be set up in just under one hour and breaks down to be shipped easily to any location.

The SPC-HC captures actors with a multiple camera array rig that shoots with polarized light to provide a diffuse pass (for texture) and the polarized capture to record the specularity. There is also, “a projection pass to capture any difficult materials like shiny black leather for instance,” explained Hakim, when Fxguide sat down with him to discuss with the Jumanji capture process.

FXG: How many cameras in the portable rig?

JH: The rig right now contains 150 cameras set up in a 360-degree fashion as I’m sure you’ve seen and we have 12 higher-res cameras situated in the front of the rig, in the direction the actor is facing, for capturing primarily the face.

FXG: Did you do a FACS ROM (Range of Motion) for the actors?

JH: A lot of vendors I work with have specific facial expressions they would like us to capture, that may be specific to the scene but typically we capture about 6 shots to sample the elasticity of the face. We aim to be as efficient as possible for the actors, as we only want to take up a few moments of their precious time. Most of the time, we are unable to go through a whole gamut of expressions (even though I know most vendors would love that) but I’m sure the actors would want to murder us if we did! We typically see a lot of people over and over, so it makes our job easier if they aren’t dreading the interaction with us.

FXG: Do you get the actors to provide any special, actor specific expressions?

JH: : I am not in front of a monitor like Mark (Breakspear) is most of the time so I don’t know if there is a unique expression that is relevant to the scene, but Mark does come over and will give additional notes to the actor or myself to make sure he is getting everything he could potentially need for post.

FXG: How far do you take the data, before handing it on to the various vendors? Do you do the scan to scan correspondence, for example? I assume it is not moving capture (Medusa style)?

JH: : I process many of the scans when I have an opportunity to but more often than not I’m scanning so many different items during the day I won’t have time to touch anything for a while. I focus on the (non-character) Lidar scans when I have downtime because I’m able to do those on my laptop, whereas a character or prop is a bit more heavy lifting technically. A lot of the orders start early on in the production, so I was on the project for effectively 3 months.

Yes, you’re correct we haven’t ventured into motion capture yet so all the characters are standing in a modified t-pose to capture the most amount of texture possible.

FXG: I think you output 16K textures is that correct? How do you calibrate the colour temp and colour space? Is it just via an in shot reference card?

JH: Yes, we output 16k textures and deliver that with the obj file to the production house or vendor. The majority of the cameras are set to auto-balance which is usually perfectly fine because when we set up the rig we are usually far away from any extreme lighting conditions, that would call for a correction.

The rig has LED strips to light the characters as evenly and neutrally as possible. For Jumanji most of the time we were in a large black tent to offer privacy as well as to eliminate any sunlight coming into. The rig is also set up with a Macbeth chart inside so any potential adjustments can be made afterward if necessary.

FXG: Thanks so much Josh,

JH: Let me just add that Mark is awesome to work with, its really a testament to his abilities that he is able to do his job so well and maintain everyone’s passion for the film, even after a long production day and all the hours that people have to put in. People around him are just as enthusiastic after a 15 hour day as they were when they started, so my hat is off to him as a supervisor.

In the end, the Action-Adventure-Comedy-Fantasy film’s 1900 shots were delivered on a very tight schedule, with just 45 minutes to spare. Jumanji: The Next Level opened at the top end of industry expectations and has gone on to be a major box office hit of the summer, with over $320 million at the box office so far and still performing strongly.